By the time the Iran–Iraq War ended in July 1988, Saddam Hussein’s Anfal campaigns had decimated Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) forces in northern Iraq. The Ba’ath regime then turned its attention to the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) peshmerga in the Bahdinan region, south of the border with Turkey.

When the villagers of Kureme were surrounded by the Iraqi army in 1988, just south of the Turkish border, they feared a massacre. With all escape routes blocked, they contemplated a radical solution to their predicament: mass suicide.

In late August that year, as the Iraqi regime launched gas attacks across the Bahdinan region, more than 100,000 Kurds fled in panic, among them 86 villagers from Kureme.

With all escape routes blocked, the villagers of Kureme contemplated mass suicide

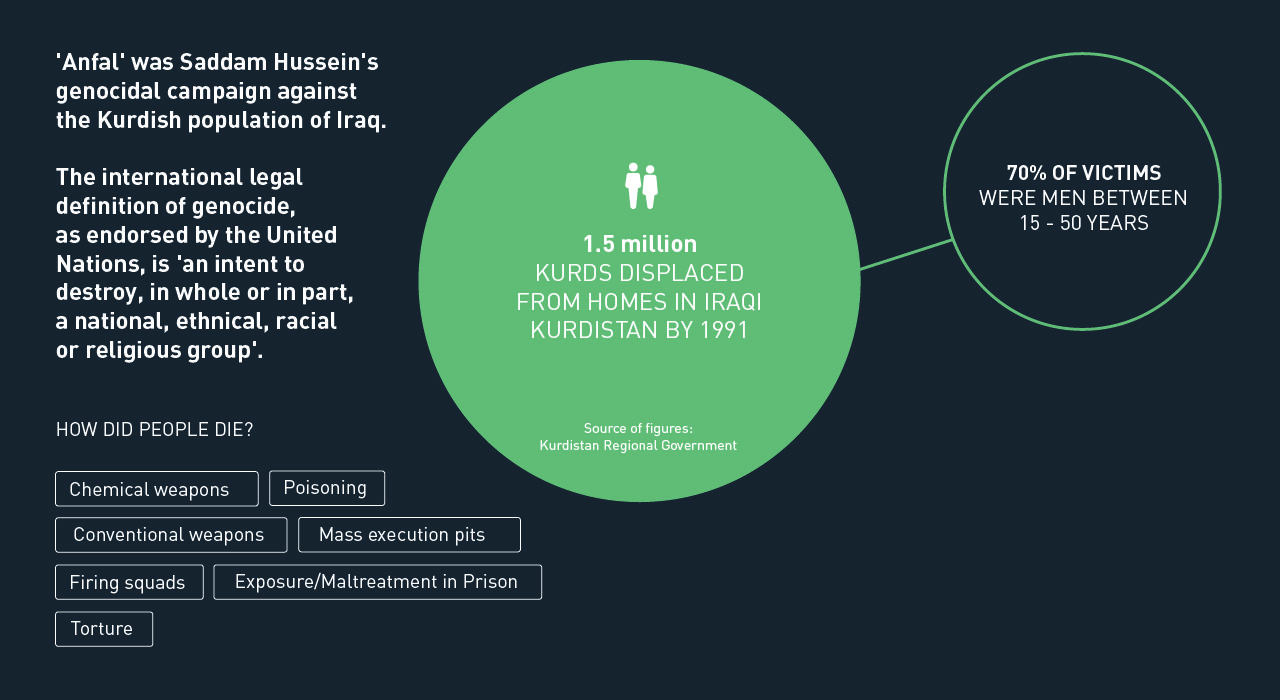

These attacks were the culmination of Saddam’s Anfal campaign against rural Iraqi Kurds, which led to the deaths of up to 182,000 people in the space of just over six months.

The Eighth and Final Anfal campaign, which came just weeks after the Iran-Iraq war had ended, triggered a mass exodus from Bahdinan towards the border with Turkey. Fleeing villagers pleaded in vain with border guards to let them through as Iraqi tanks moved remorselessly towards them. Only much later were Kurdish villagers allowed across, but it was too late for Kureme’s desperate population.

In August 1988 Saddam Hussein ordered the Iraqi army to attack 70 Kurdish villages in the Bahdinan region of Iraqi Kurdistan. In panic, rural Kurds fled to the nearby border with Turkey. However, the Turkish border force refused to let families cross, sending them back to face death or imprisonment at the hands of the Iraqi army.

’We were all exhausted,’ says Qahar Khalil Mohammed, a peshmerga Kurdish guerilla fighter. ‘We tried many times to cross the border but couldn’t.’

‘Many families gathered there with their children and belongings. Some were sleeping standing up; some were hungry, some had lost their children, and some were dead on mules. It was like doomsday.’

All of us were exhausted. We tried to cross the border into Turkey to escape the Iraqi army many times but it was not possible

With food supplies dwindling, most of the villagers decided they had no choice but to return to Kureme, hoping for an amnesty but fearing the worst if captured.

They knew they would be punished severely for their support of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) led by Masoud Barzani, son of the legendary Kurdish leader Mullah Mustafa. Over a period of five years, they had seen Kureme destroyed three times in revenge for Barzani’s alliance with the Iranians.

On the outskirts of Kureme, they were surrounded by Iraqi troops.

‘Some said we should kill ourselves,’ says Qahar. ‘Others said we should surrender. A group of us decided to commit suicide but our families began to weep and my father stopped us. He took our rifles and said, “I won’t allow this. We live together and we die together.” ’

A group of us had decided to commit suicide but my father took our rifles from us. “I won’t allow this,” he said. “We live together and we die together”

Although the villagers’ situation seemed hopeless, a decision was taken to send a small group of villagers to try and negotiate safe passage with the Iraqi lieutenant in charge of the troops surrounding their village.

‘They told the officer that they needed assurances from the Iraqis to persuade the families to give themselves up,’ says Karim Naif Hassan, a young boy at the time.

With their route to the Turkish border blocked, Kureme’s inhabitants were forced to return homewards. Some of them would later contemplate suicide. As the villagers returned the Iraqi army intercepted them and singled out 33 men for execution.

‘If there’s no guarantee, they won’t come and will all probably commit suicide,’ the villagers told the officer.

The lieutenant’s response offered hope. ‘I swear on the Holy Koran and on behalf of Saddam and the Ba’ath Party that no one will be harmed. Let them come,’ he said.

The women and children screamed in fear as 33 men and boys from Kureme were led away by Iraqi soldiers

When told of the outcome of the meeting, all the villagers said they had faith in the Koran but not in Saddam or the Party, but agreed to surrender.

They were then led to the centre of Kureme where the men were separated from the rest of the group. The women and children screamed in fear as they were taken to the nearby village of Mangesh and 33 men and boys were led away.

The lieutenant tried to calm the women by promising their loved ones would soon rejoin them. But the men had been stripped of all their possessions and marched in single file to fields just outside the village.

As they were ordered to get down on their knees, a small boy asked aloud what was going to happen to them.

‘Nothing,’ said Abubakir Ali Said, a peshmerga who, like Qahar, had returned home when he learned Kureme was threatened.

But there was no doubt in his mind what lay ahead. Some of the men screamed, while others prayed and begged each other for help as the soldiers accompanying them, 16 in all, aimed and then fired their AK-47s.

ABUBAKIR ALI SAID, a badly wounded survivor from Kureme, was lying on his back and unable to move when Iraqi soldiers approached him.

Abubakir Ali Said urged everyone to run away when the shooting started and himself hid in a clump of vines. But the lieutenant spotted him and ordered his soldiers to open fire.

‘It hailed bullets,’ says Abubakir. ‘I was shot in the leg and fell down wounded.’

‘They reloaded their magazines two or three times and once they’d emptied them felt sure everyone was dead,’ says Karim. ‘But to make sure they were ordered to fire a single bullet into each person.’

The soldier stood over me and aimed for my forehead. Thank God that bullet wasn’t fatal

Qahar Khalil Mohammed was the first in line

‘The soldier stood over me and shot me here,’ says Qahar, pointing to his forehead. ‘Thank God the bullet didn’t seriously harm me.’

Karim Naif Hassan lay under three corpses and could only see the boots of the soldier standing over him. When they had finished shooting, the soldiers moved off and then there was silence.

After the Iraqi army’s mass execution of the inhabitants of Kureme village, 27 bodies littered the nearby fields. Four of the six survivors, all badly wounded, helped each other escape and hid in nearby caves for 11 days living off water, sour grapes and tomatoes

‘I stood up and was covered in blood,’ said Karim. ‘But I realised I was OK. I’d been hit by many times but not fatally wounded.’

Lying nearby were the bodies of his cousin, Abdul Rahman, two friends, Sadiq and and his brother Hamid, and two other brothers from Kureme: Salah and Khalid Mustafa. ‘I saw 27 corpses in all,’ says Karim.

I stood up and was covered with blood. I realised I had been hit many times but not mortally wounded

Meanwhile, the Kureme women and children heard the sound of gunfire as they were pushed and prodded by Iraqi soldiers up a nearby hill.

‘We twice heard the sound of shooting, the ‘duh, duh, duh’ of gunfire,’ says Fairooz Taha Saadi whose husband had been led off with the other men.

Iraqi soldiers separated the women of Kureme from the men and forced them to march up Mangesh hill. On the way, they heard shooting.

‘The firing is the sound of joy,’ the soldiers told Fairooz. ‘Your men will be with you soon.’

‘You’ve killed them, Fairooz replied. ‘I know you’ve killed them.’ But they denied it.

The women and children heard shooting on three more occasions. One of them, Samia, whose son had been led off with the other men, reached the top of a hill overlooking Kureme and shouted down to the others.

‘They’ve shot them all – they’ve all been killed.’ At this moment she suffered a heart attack. She died weeks later at a prison camp near Mosul.

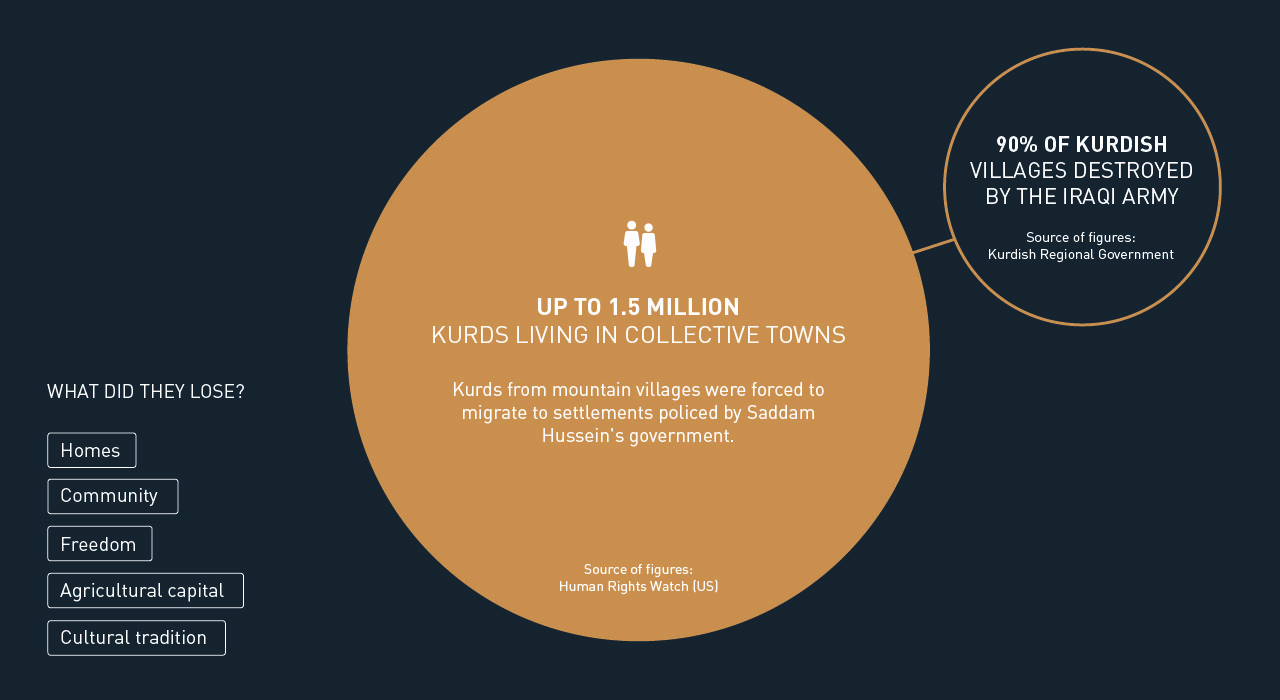

About 14,000 Kurds were captured in Saddam’s Eighth and Final Anfal. Most ended up in the Nizarka prison in Duhok, where they were treated harshly. Men were separated from their families and beaten with sticks and bricks, before the Iraqis forced them onto trucks. They were never seen again.

Six men survived the execution, including Qahar who had been shot in the back. Four of the six wounded men tried to escape into the mountains, where they lived off sour grapes, wild tomatoes and water for 11 days.

‘We knew we’d die of starvation or from our injuries,’ says Qahar. ‘We lost faith in ourselves and in God. All our relatives had gone. When your children are gone, and your brother, mother and father have been taken, you think, “What will become of me?”’

When your children have gone and your brother, mother and father have been killed, you think, “What will become of me?”

The four survivors sought refuge in a nearby village but were handed over to the Iraqi army a few days later. Most of them were taken to the Baharka internment camp near Erbil where they stayed for three years.

Some other men from Kureme were imprisoned at the Nizarka fortress near Duhok. Most Anfal captives were brought here. On arrival, the women and children of Kureme were separated from the men, who were then beaten with concrete bricks. Within days, the men were loaded onto lorries and driven away into the night. They never returned and were never seen again – all are presumed dead.

The Anfal survivors in the Baharka internment camp were the mothers, wives and children of Kurdish men executed by the Iraqi authorities. When they arrived they were supported by the local people of Erbil who brought supplies to the camp, but food and water were still in short supply and many of their children died of starvation.

The women and children of Kureme were eventually moved to the northern outskirts of the Kurdish capital, Erbil, where they were dumped at the side of the road. They had no shelter, no food and no water. Yet they were saved by the generosity of the local townspeople who confronted the Iraqi authorities and brought them tents and supplies. Medicines were in short supply, however, and many children died from disease.

The Anfal survivors of Kureme finally returned home after the 1991 Gulf War.

‘Saddam Hussein treated us unjustly,’ says Khayal Ahmad Amin. She lost her husband in Kureme and two children in Nizarka. ‘He destroyed villages and made people poor, hungry and thirsty. He destroyed us. He killed everyone. Our hearts are not at peace.’

Saddam Hussein treated us unjustly. He tried to kill every one of us

More than 50 villagers from Kureme died during Anfal. FAIROOZ TAHA SAADI waited three years for her husband to return, but in 1992 American forensic specialists uncovered mass graves in Kureme. They discovered the pyjamas her husband was wearing when captured. This established beyond doubt that he had been executed by the Iraqis.