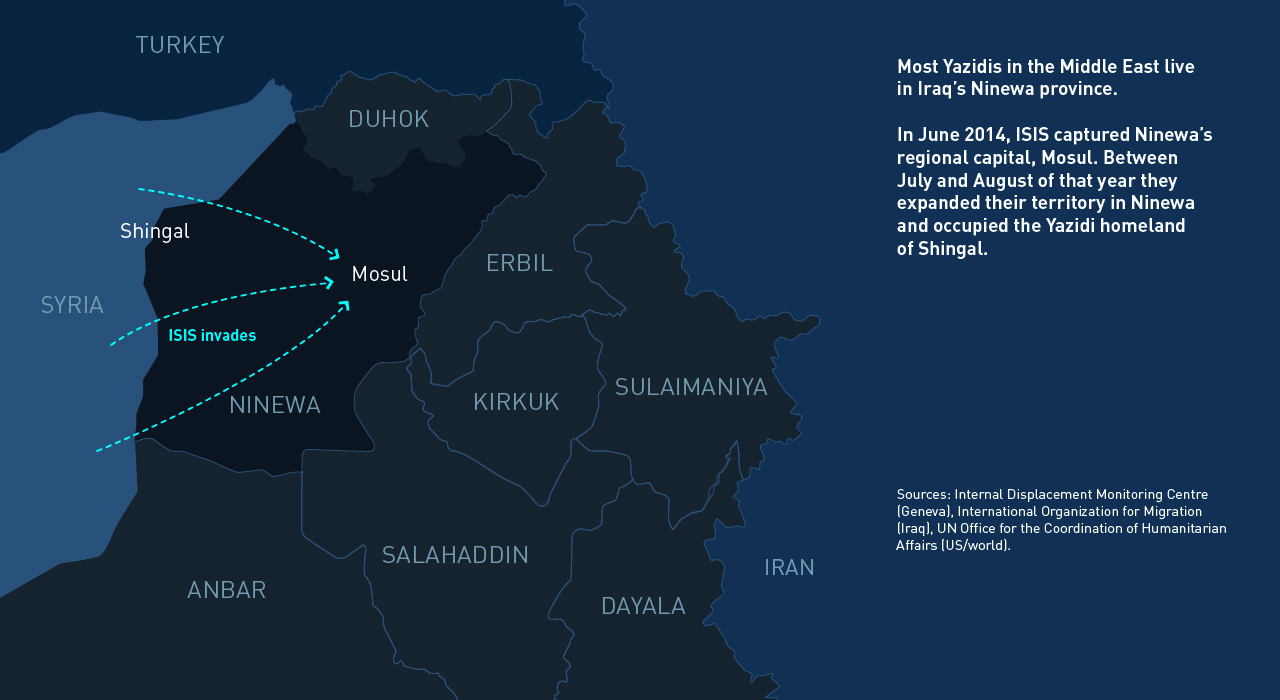

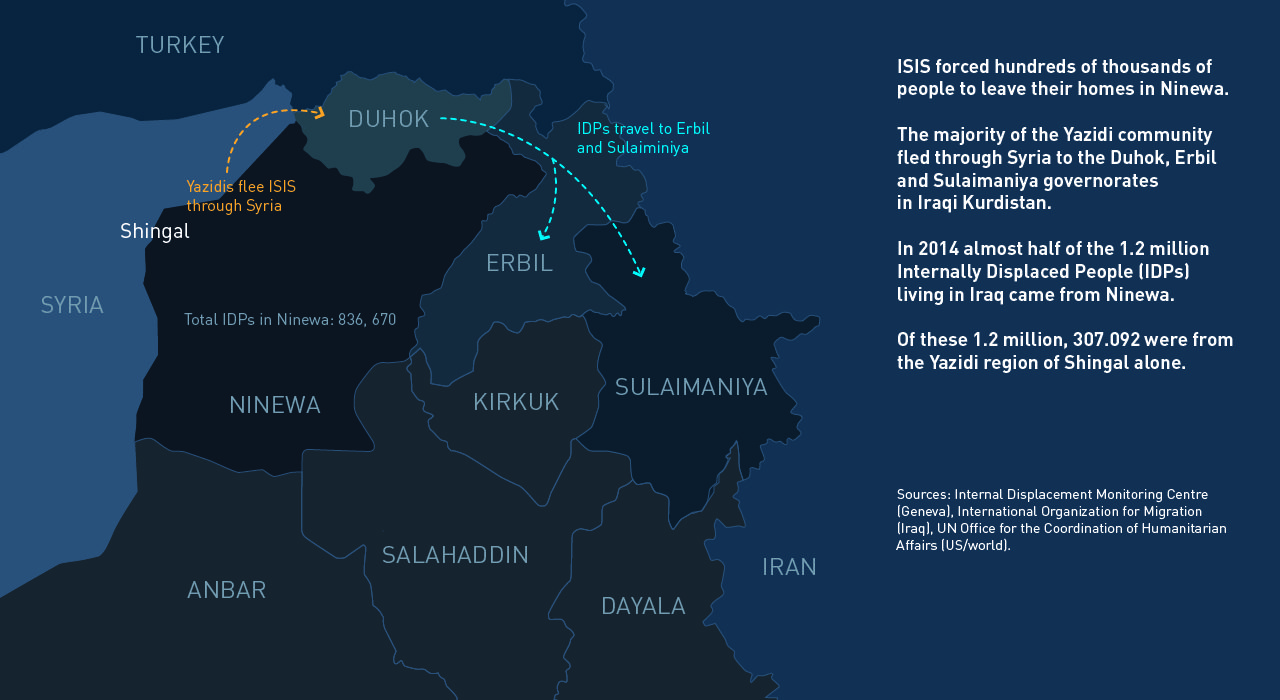

After ‘Islamic State of Iraq and Syria’ (ISIS) extremists invade the homeland of the Yazidi people of northwestern Iraq in August 2014, hundreds of thousands are forced to flee via Sinjar mountain in an attempt to reach the safety of Iraqi Kurdistan. ISIS treat those left behind brutally: thousands of Yazidi men are executed by ISIS soldiers and thousands more women are enslaved.

Khawla Chatto will never forget the last time she saw her father.He was imprisoned on a farm in the Yazidi heartland of the Sinjar region in northwestern Iraq, and faced execution by fighters from the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Her father Khalil Chatto, a businessman, had fled his previous home in nearby Tel Uzeir. Tel Uzeir is “a collective town,” largely populated by Yazidis who were uprooted from their traditional villages by the Ba’athist regime of Saddam Hussein. This forcible resettlement took place during the early 1980s.

In a surprise attack, heavily armed ISIS fighters drove towards Khalil’s brother’s farm. The Chatto family immediately begged for mercy

Yazidis like Khalil therefore lived in fear of hostile Sunni Arab tribes surrounding their communities west of the Iraqi city of Mosul. When news of an invading ISIS army reached him he, like thousands of others, abandoned his home in panic, seeking a safer place of refuge.

Early on 6 August 2014, Khalil loaded his wife and children into his car and then drove to his brother’s farm, which was an hour’s drive away. He made repeated return trips to fetch other relatives to take them to the farm, about 100 in all. They felt safe there, which is why they were so shocked when heavily armed ISIS fighters, dressed in their characteristic uniform of tunics and short baggy trousers, drove towards Khalil’s brother’s farm in five vehicles.

After ISIS overruns the Yazidi heartlands in northwestern Iraq they immediately demand that all Yazidis either convert to Islam or face death. The male members of the Chatto family, who are from the town of Tel Uzeir, refuse and their fate is sealed.

The Chatto family immediately surrendered their weapons and begged for mercy.

‘We told them, “We’ll do whatever you want just don’t kill us,”’ says Khafshe Hassan Chatto, Khalil’s wife.

She was locked away with about 20 other women and children whilst the men were stripped of their phones, watches and money, and put under guard in one of the side rooms. Some relatives tried to run away but they were quickly recaptured by ISIS men.

Khalil could only have feared the worst when he saw his daughters being driven away by ISIS soldiers. He was well aware of how the Islamic extremists viewed the Yazidi people

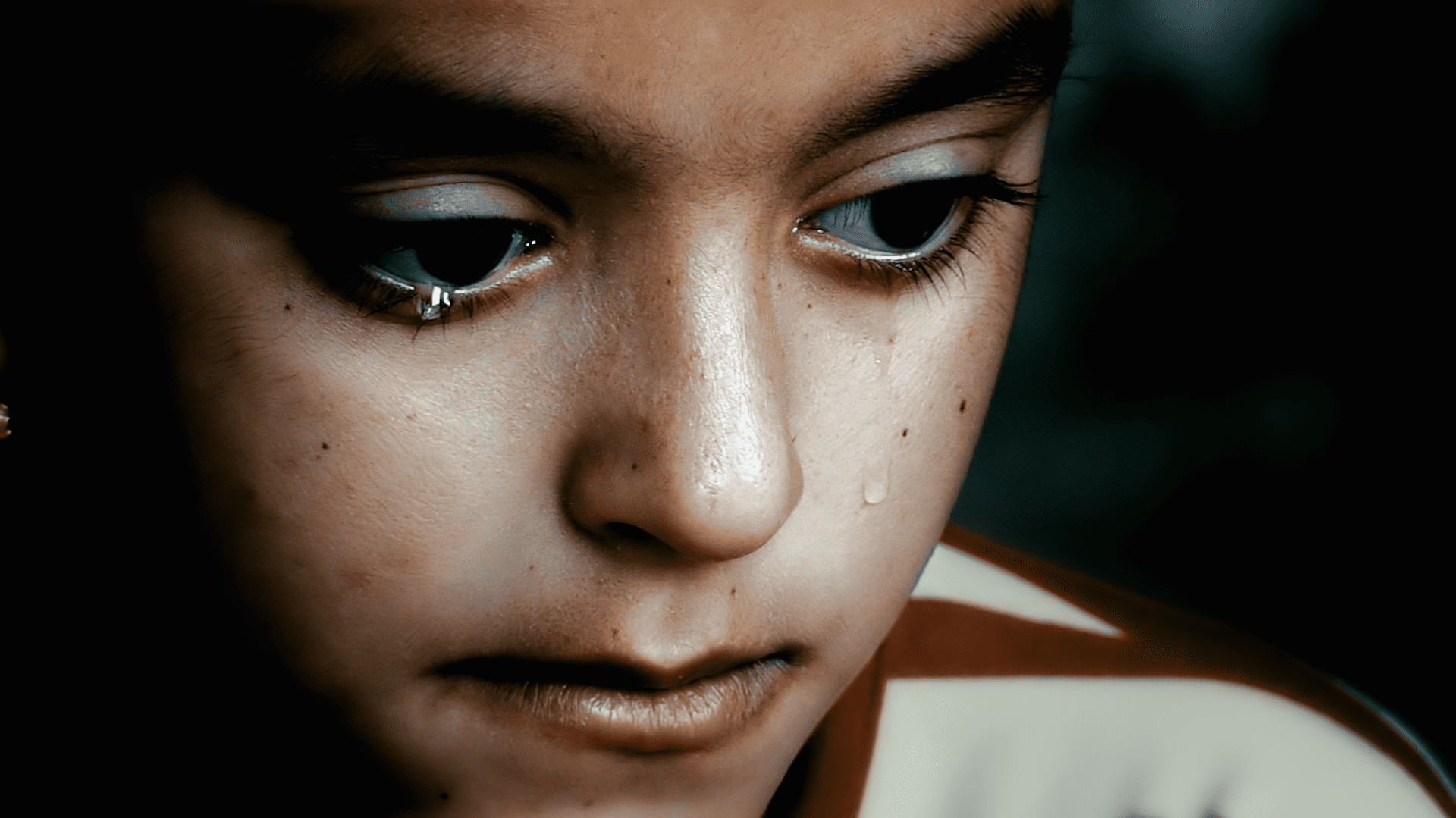

The Jihadis then separated girls and young women from their families and loaded them into cars belonging to the Chatto family. From inside the vehicle, Khawla spotted Khalil, her father, staring at her through a small window at the side of the building and she returned his gaze. She was frightened she would never see him again.

‘I kept eye contact with him until the last moment,’ says Khawla. ‘My father was unique. He loved his family beyond measure. He always said he wouldn’t let his daughters live away from him. I loved him so much I would have sacrificed my life for him.’

Khalil could only have feared the worst when he saw his beloved daughters being rounded up by ISIS fighters. He and his family were only too aware of how the Islamic extremists viewed the Yazidi people.

In 2007 the Yazidis are the target of the largest global terrorist incident since the 11 September 2001 attacks on the United States. Up to 800 lives are lost in Tel Uzeir after multiple car bombs are detonated in a local bazaar, and the Yazidi inhabitants of the town are convinced Arab extremists are responsible. They hang pictures of the deceased inside a local cultural centre.

This was not the first time the Chattos had suffered at the hand of Islamic extremists. Just seven years before, the Yazidis of Tel Uzeir had suffered a terrorist attack which was hardly noticed by the outside world but shook their community to the core.

In 2007 four truck bombs were detonated in the Tel Uzeir bazaar, killing up to 800 people. The high number of casualties has led many to describe the Tel Uzeir bombings as one of the worst terrorist incidents since the 9/11 attacks on the United States in 2001.

The Chattos lost most of their possessions that day including five shops and a restaurant in the bazaar. Khalil’s brother and his two sons-in-law also died. His son Ibrahim, who was near the explosion when it happened, was never seen again although the Chatto family clings to the hope he may still be alive.

The 2007 explosion reversed the Chatto’s fortunes. For years they had prospered. They had enjoyed a good standard of living, owned their own house, a car and a gold and cement business. The family was close knit and well respected within the Yazidi community. But with their livelihood destroyed and four members of their family gone, they found it difficult to rebuild their lives.

A sense of deep insecurity pervaded their household. Khalil was hugely protective of his daughters and could not bear for them to be out of his sight.

‘If we were out for the day, he would call us and ask us to go back because he missed us,’ says his daughter, Khawla. ‘He always said, “I don’t want my daughters to leave my house before I’m dead.”’

The Chatto family tell the story of the terrible day in August 2014 when Islamic extremists from ISIS brutally executed both male and female members of their family.

The unexpected arrival of ISIS fighters on his doorstep in August 2014 was the fulfilment of Khalil’s worst nightmare. He and the other male captives were immediately given a stark choice: convert or die.

His wife Khafshe and his three small children begged the ISIS fighters not to kill them, but were told that converting to Islam was their only hope for survival.

‘Our men said, “We can’t convert. We are Yazidi,” recalls Khafshe. They asked, “Who is your God?” They replied, “Melek Tawwus.”’

This answer sealed their fate. The importance of the figure of Melek Tawwus (literally translated: “Peacock Angel”) to the Yazidis gives them an undeserved reputation for being devil-worshippers. They believe that Melek Tawwus, known in other faiths as Satan, should be a revered figure because he repented after disobeying God. For these beliefs the Yazidis have suffered extreme persecution over the centuries and no mercy could be expected from an extremist Islamic cult like ISIS.

Khalil’s wife and children were in the farmhouse when the execution occurred.

‘They killed my husband, my brother-in-law and five men from my brother’s family,’ says Khafshe. ‘My husband’s cousin escaped but was captured again. They beheaded him.’

Khafshe also lost two of her six daughters, Amina and Nahida, who were shot dead as they tried to flee. The remaining captives were then doused with petrol.

‘They said they’d set us on fire,’ says Khafshe. ‘They prepared to kill everyone but one of them received a telephone call and because of that they didn’t burn us all.’

Khafshe spent two hours with her two young children, Bassem and Farhad, next to her husband’s body.

Khafshe’s daughters Amina and Nahida were shot dead as they attempted to flee. Later the ISIS fighters doused their captives with petrol and threatened to set them on fire

The ISIS fighters then left but returned shortly afterwards. ‘When they saw everyone had gone except for us and and our mother they waved goodbye and drove off,’ says Bassem.

‘For two hours we poured water on my father and covered him in a blanket. We thought he’d open his eyes but he was dead,’ says Farhad.

Khafshe and her three small children cried and cried.

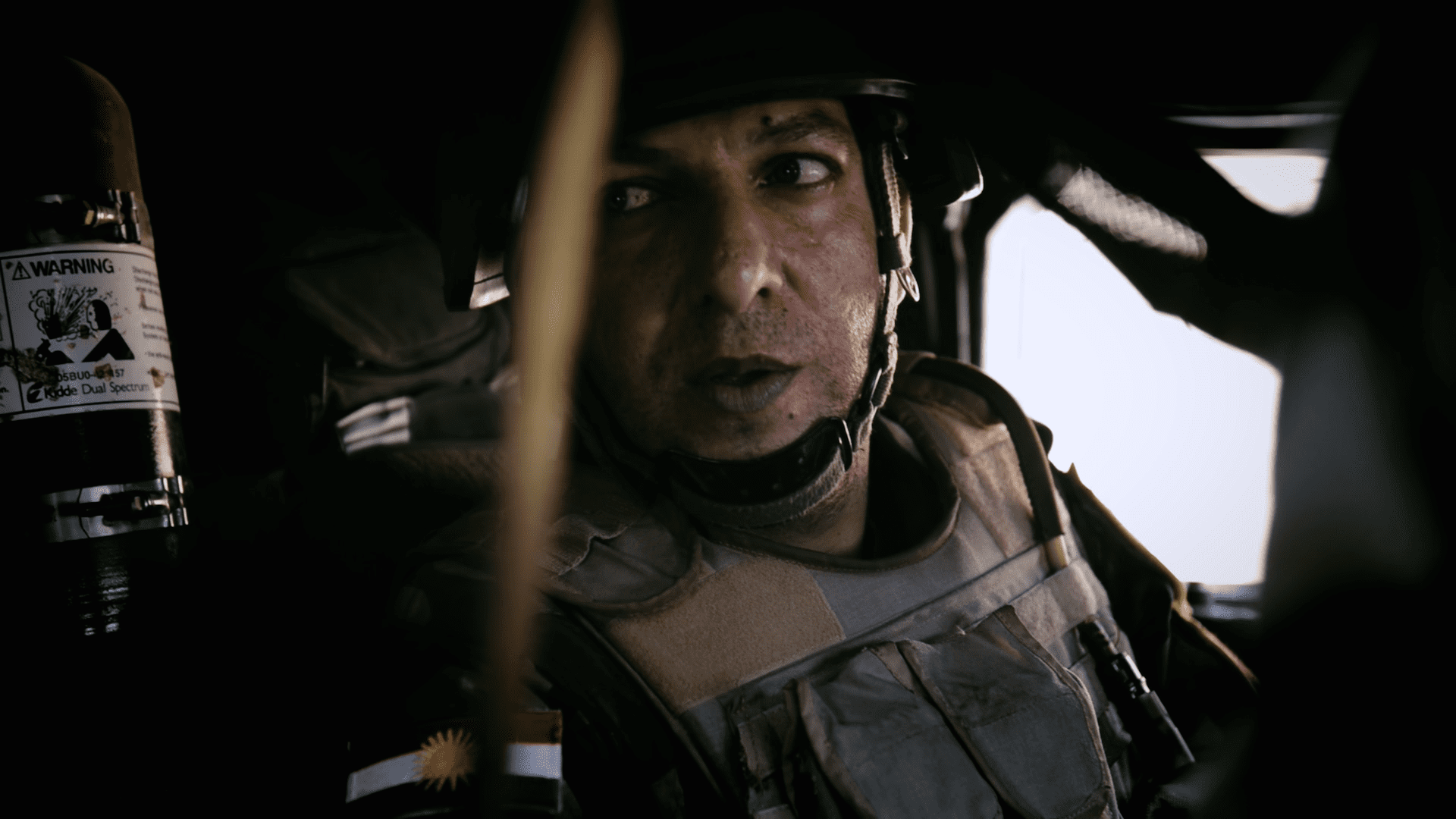

General Mansour Barzani, Special forces Commander for the Kurdish peshmerga, states that ISIS is a danger to the entire world – not just Iraq and Syria. On a visit to Mosul Dam, just two kilometres from the battle frontline, Barzani explains the Kurds are not only defending themselves but all of Iraq’s ethnic minorities, and notes the Western powers have a vested interest in their fortunes.

Fleeing the farm with other members of her tribe and her children in tow, Khafshe’s group were forced to leave the wounded behind under a tree.

Travelling in fear for their lives, her group joined tens of thousands of Yazidis headed towards Sinjar mountain, with the intention of crossing into Syria to the northwest.

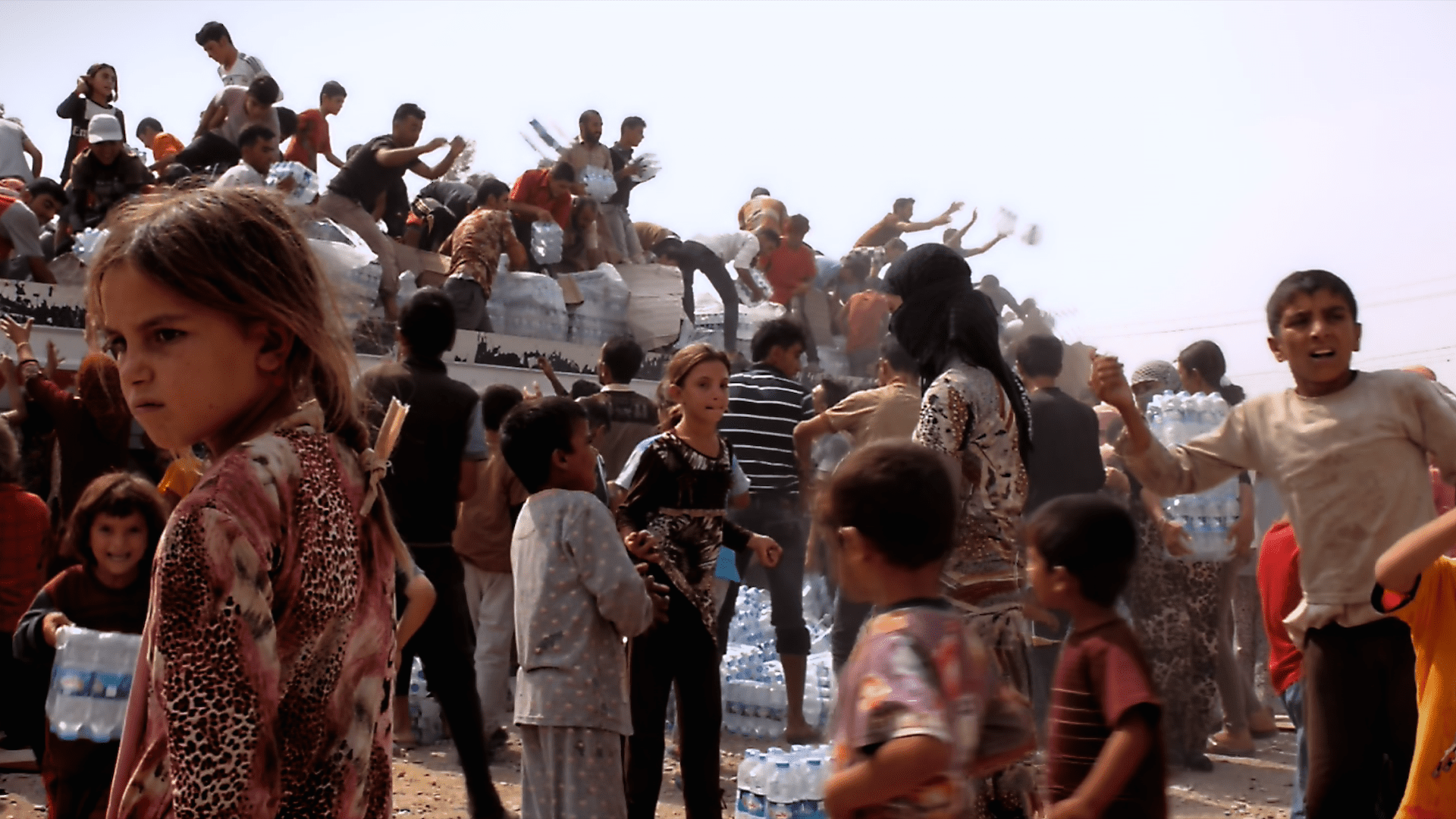

Travelling with little food nor water, they struggled for eight days to reach their destination. During this period, Khafshe repeatedly rang her 21-year-old son, Khairi, in Erbil to seek help.

‘There was a telephone call from them every two days,’ says Khairi. ‘I was the only surviving male from my family and I wanted to be with them even if it killed me.’

Khairi decided that he, his uncle and his cousin would mount a rescue operation to save his mother and sisters. “I was the only surviving male from my family: I wanted to be with them even if it killed me”

Khairi decided he, his uncle and his cousin would mount a rescue operation. They drove two cars to Sinjar mountain along a narrow road just inside the Syrian border, running the gauntlet of ISIS artillery on either side of their route as they travelled. They heard the sound of shells exploding above them but escaped unscathed.

‘When we reached my mother and the children, they weren’t recognisable,’’ says Khairi. ‘They were so dusty and dirty. They looked awful.’

Khairi drove some members of his family to safety in Iraqi Kurdistan but his sisters were not as fortunate.

After being forced to leave the farm near Tel Uzeir, Khairi’s sisters Khalida, Wahida, Zaytun and Khawla were taken to Mosul to the east of Sinjar. They were housed in a large municipal building known as ‘Galaxy Hall’ together with about 1,000 women, girls and young children.

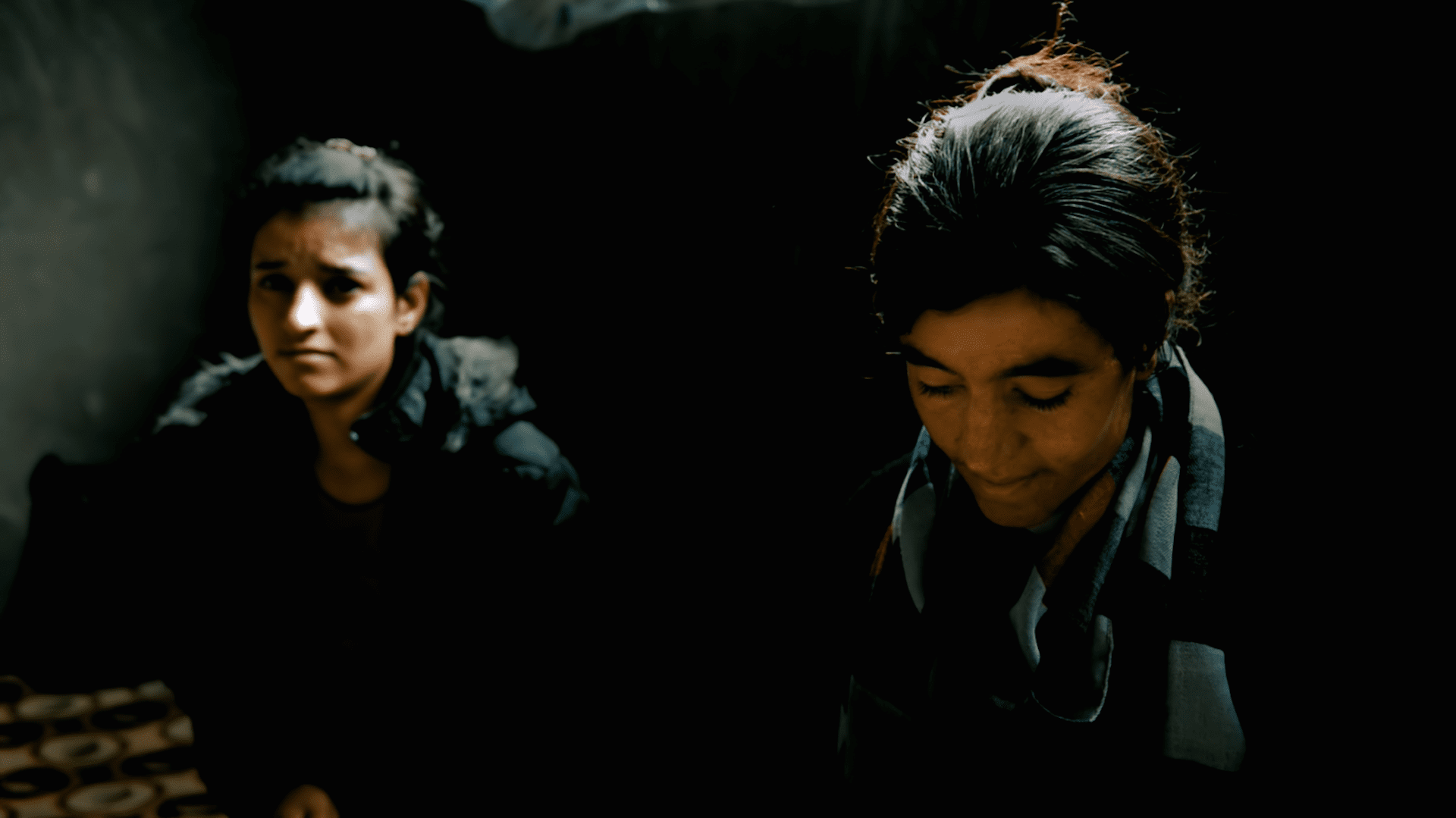

Wahida and Zaytun Chatto, who were abducted by ISIS soldiers, describe how they and other girls were forced to convert to Islam and then sold to jihadi fighters for between US $1,000 and $6,000. They were regularly beaten and traded time and time again by their inhumane captors.

In all, about 20 girls were then taken to a three-storey building in the city where they were visited by two ISIS emirs and a group of military commanders – about 15 men in all.

‘They told us to convert to Islam so we converted,’ says Wahida. ‘Then they said they didn’t believe our conviction and that we would always be Yazidi. They beat everyone and made them swear allegiance to Allah.’

‘That night each of us was taken by force,’ recalls Wahida. ‘One girl was married three times, another twice. A ten-year-old child was given to someone and married off. They were given as gifts. They all laughed at the girls.’

“It’s wrong, she is too young,” Zaytun protested to the Arab men trading an eight year old Yazidi girl for money. They replied, “It’s acceptable in our religion”

‘Some were sold for US $1,500 dollars, some for US $3,000 and others for US $6,000. Just like that,’ says Wahida. ‘Some took three or four girls. Their leader took seven. Women were separated from their children. They took everyone.’

After being separated from her sisters, Zaytun was moved four times to villages and towns across Sinjar. In Tel Qassab she tried to save an eight-year-old girl from being sold to an elderly man.

‘The little girl would cry and ask, “Zaytun, what should I do?” I told them, “It’s wrong. She’s too young.” They said, “It’s acceptable in our religion.”’

The children of Yazidi families did not escape the extreme cruelty of ISIS. Small boys were held captive and forced to perform weapons training, even if they were physically incapable of holding a gun, while small girls were told they would be shot dead or hanged from a tree if they refused to speak Arabic.

‘They were going to take me to Mosul but I didn’t allow it. So they beat me, tied my hands and threw me out of a window. Then they put a gun to my head and demanded I declare that Allah is the only God. They broke one of my fingers. They sold the girl for US $3,000 to a 60 or 70 year old Syrian. He took her saying she was ‘nice and young’.

Zaytun dreamed of escape. When she heard there were plans to try and sell her off in another Middle Eastern country, she decided she had to act.

Under cover of darkness, she fled with a 13-year-old Yazidi girl towards Sinjar mountain.

‘I carried a knife with me,’ says Zaytun. ‘I thought if they caught me I’d kill myself before they can touch me. I prayed to God to save us.’

They walked for three days and nights until they reached their destination. There they met friendly peshmerga who help her return to her family in Iraqi Kurdistan.

I would not go to Mosul with the Arab men, so they beat me, tied my hands and there me out of a window. Then they put a gun to my head and demanded I declare that Allah is the only God

Zaytun’s sisters, Khalida and Wahida and their 12-year-old cousin, were held at an ISIS base in Mosul.

Growing increasingly desperate, they planned their flight. Watched closely by ISIS fighters during the day, the girls were locked up at night and left on their own. They finally managed to steal a key to the main door and, dressed in black, disappeared into the night.

They entered a neighbour’s house and begged for help. The family there offered to drive them to Kirkuk on payment of US $18,000. They left at four a.m. and reached Kirkuk safely after phoning their brother, Khairi. He arranged to pay off their drivers with money borrowed from a relative in Germany.

He drove to Kirkuk and reunited them with their mother, brothers and sisters in Duhok in Iraqi Kurdistan. There they lived in an uncompleted apartment block before being helped by a German NGO, Luftbruecke-Irak (also known as ‘Airbridge Iraq’), to reach Stuttgart in Germany.

Khairi Chatto pays for his sister Khawla’s release from ISIS captivity and there is an emotional reunion at Iraqi Kurdistan’s border with Syria. However, he does not tell Khawla that ISIS soldiers killed their father.

Khairi remained behind to organise the release of his remaining sister, Khawla, who had been moved to an ISIS military base at Shadaddeh in Syria.

Khawla had come close to committing suicide during her captivity at the ISIS camp.

‘I thought of ending my life,’ she says. ‘But the thought of being reunited with my family kept me alive.’

She managed to telephone her brother in Dohuk and tried to escape but was betrayed by a Syrian family whom she had approached for help. Some 10 months after first being captured, Khawla tried again.

Now living in Mayadin in eastern Syria, she arranged for smugglers to take her – on payment of US $5,600 dollars arranged by Khairi – to areas of Syria controlled by the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the Syrian Kurdish militia. From there she moved to the border with Iraqi Kurdistan, where she was met by her brother. Having safely transported Khawla away from the border, Khairi finally delivered the devastating news to his sister that the ISIS fighters who attacked their uncle’s farm had also killed their father.

“I thought of ending my life,” says Khawla Chatto. “But the thought of being reunited with my family kept me alive”

‘I wished I had died before hearing that,’ Khawla told Khairi.

Khawla had spent 10 months in captivity and shortly after her release rejoined her family in Stuttgart. Khairi, however, was excluded from the Luftbruecke-Irak programme which had airlifted his mother to safety, along with his other sisters and young brothers months beforehand.

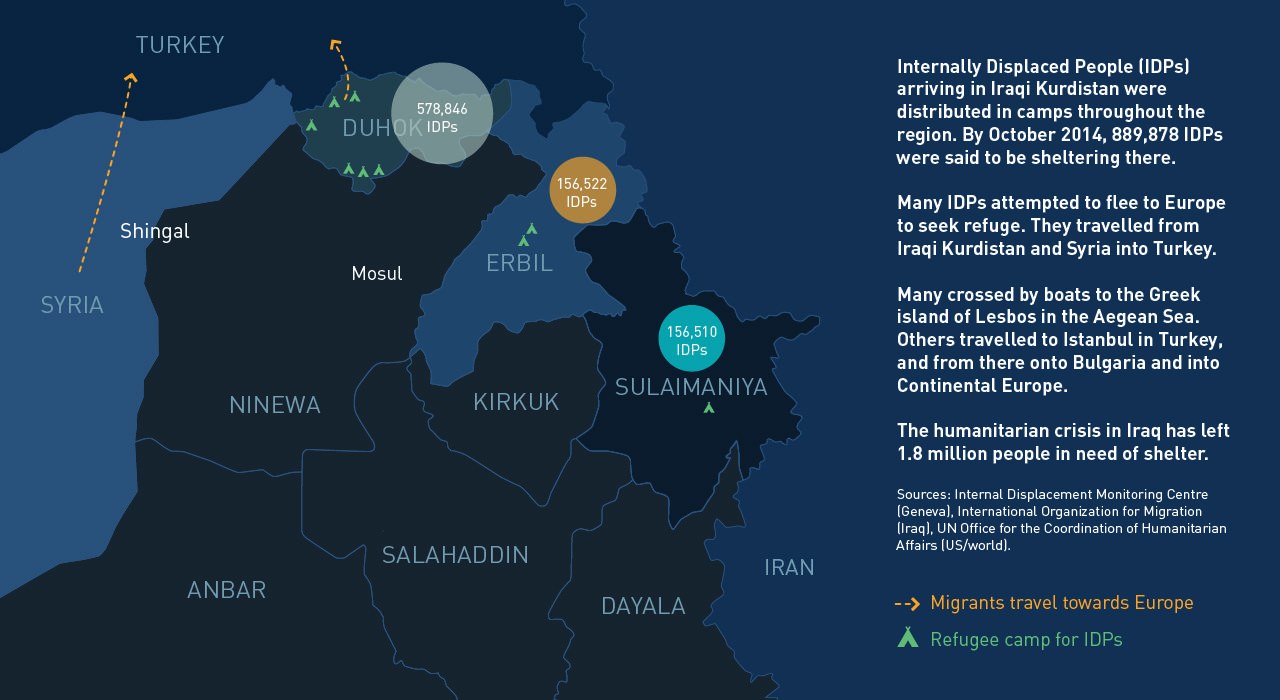

Desperate to rejoin his family in Germany, Khairi and his wife Amal decided to join the flood of migrants heading north towards Europe.

On a 2,500 km journey which lasted 15 days, they travelled from northern Iraq into Turkey and then across to the Greek island of Lesbos in the northern Aegean Sea. Their route then took them through Macedonia, Slovenia, Austria and finally into Germany. They were finally reunited with their family in Stuttgart at the end of November 2015.

‘It as a very dangerous journey but my family means everything to me,’ says Khairi. ‘Myself and Amal were prepared to risk everything to be with them.’