SADDAM HUSSEIN pursued a state sponsored campaign of terror and ethnic cleansing with the al-Anfal military operations of 1988, inflicting both physical and psychological traumas on the Kurdish people.

What is Anfal?

Anfal was a series of eight military campaigns conducted by the Iraqi government against rural Kurdish communities in Iraq, which lasted from 23 February until 6 September in 1988.

The word al-Anfal is religious in origin: it is the name of the eighth sura or chapter of the Koran, and literally means ‘the spoils’, as in ‘the spoils of battle’. More specifically, al-Anfal refers to the spoils of the first battle of the new Muslim faith at Badr in 624 A.D. in what is modern day Saudi Arabia’s province of Hejaz.

As President of Iraq, Saddam Hussein frequently used religious language when describing the actions of his secular Ba’athist regime, portraying Arabs as true defenders of Islam and Kurds as infidels.

For rural Kurds, Saddam Hussein’s massive assault during Anfal may have felt like the wrath of a violent deity, as his government exercised the power of life and death over them. Genocide of such a dimension was unprecedented in the modern history of Iraq.

The Iraqi Ba’ath Party had long viewed the Kurds of Iraq as non-Arabs living on Arab lands. After the collapse of their 1970 Autonomy Agreement with the Kurdish leadership, the Iraqis quickly stepped up their policy of ‘Arabisation’ in Kurdish regions of northern Iraq – forcibly resettling the Kurdish population and replacing them with Arabs.

Understanding the Iraqi Ba’ath Party’s bitter hostility towards the Kurds

Saddam Hussein claimed Anfal was a direct punishment of the Kurds for supporting Iran in the Iraq–Iran War of 1980 to 1988. Yet it was also opportunism: Baghdad had long wanted to crush Kurdish ambitions for self-rule and establish undisputed Arab control over Kurdistan’s oil.

After the Ba’ath Party’s successful second coup in 1968, its grip on power was weak, so it sought to consolidate its position within Iraq by temporarily reaching an accommodation with the Kurds.

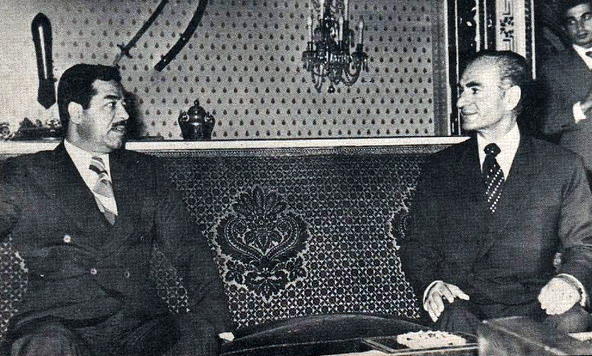

Saddam Hussein, at that time the Iraqi government’s second-in-command, signed a peace accord with Kurdish leader Mullah Mustafa Barzani in 1970 that explicitly recognised the legitimacy of the Kurdish nationalist cause. The Autonomy Agreement also nominated the Kurds to control lands responsible for half of Iraq’s agricultural production.

Yet the terms of this accord were quickly reneged upon by the Ba’athists, who refused to accept Kurdish claims to the oil-rich lands of Kirkuk and Khanaqin. Abandoning the terms of the Autonomy Agreement, the Ba’ath Party stepped up its ‘Arabisation’ programme of forced resettlement of Kurdish areas that it had initiated in 1963 after its short lived coup.

SADDAM HUSSEIN signs the Algiers Accord with the last Shah of Iran, MOHAMMED REZA PAHLAVI, in 1975.

Photograph: Iraqi state archive

Saddam Hussein defeats the Kurdish uprising in 1975

Saddam Hussein publicly accused the Kurds of accepting covert support from Iran and the United States and vowed revenge. ‘Those who have sold themselves to the foreigner will not escape punishment,’ he said in 1973.

The following year, the Iraqis announced a new agreement which claimed Kirkuk and Khaniqin for the government. The Kurdish leadership was given two weeks to submit to its terms. By rejecting the deal, Mullah Mustafa Barzani declared war with the Iraqi government, renewing the Kurdish struggle against Iraq’s new Ba’athist regime in earnest.

Barzani’s revolt was short lived, however, as he was betrayed by his principal allies, the United States and Iran. On 6 March 1975 Iraq and Iran signed the Algiers Accord in Algeria with tacit American approval, solving their dispute over the Shatt al–Arab waterway in southern Iraq. The agreement effectively ended Iranian and American support of the Kurds, crushing their uprising against the government.

Pressed on their abandonment of the Kurds the then head of US National Security, Doctor Henry Kissinger, said, ‘Covert action should not be confused with missionary work.’ Barzani was forced to order his peshmerga to end their struggle and then retreated from political life.

In 1985 British journalist Gwynne Roberts reported the disappearance of 8,000 Barzanis from within northern Iraq. MASOUD BARZANI, their tribal leader, told Independent Television News (ITN) that a large number had been executed.

PUK and KDP revive the Kurdish struggle

After being appointed President of Iraq in 1979, Saddam Hussein ordered the invasion of Iran. He sought to profit from the political chaos caused by the Iranian revolution of the same year, whilst simultaneously undermining any potential Shia rebellion within Iraq. Iraq’s ambition was to recover all of the territory conceded to the Iranians in the 1975 Algiers Accord.

When war broke out between Iraq and Iran in 1980, Iraqi troops were moved from Iraqi Kurdistan to the Iranian front. The Kurdish movement, apparently struck a mortal blow in 1975, slowly began to re-emerge but split into two main political groups: the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) led by Jalal Talabani and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), now headed by Masoud Barzani, Mullah Mustafa’s son.

As the PUK made tentative progress on a peace agreement with the Iraqi government, KDP peshmerga began to operate more freely behind Iraqi lines, attacking government strongholds in their region.

Subsequently, Saddam Hussein accused Masoud Barzani of betraying his country and collaborating with the Iranians. In 1983 he took revenge, arresting between 5,000 and 8,000 men and boys from the Barzani clan of whom Barzani was the tribal leader, before taking them to Iraq’s southern deserts where they were summarily executed.

In December 1983 the Ba’athists began to negotiate a ceasefire with the PUK in an attempt to drive a wedge between the rival Kurdish parties. These talks broke down in January 1985, however, and the strategic alliances in the region shifted as the PUK, KDP and the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP) began to recognise a common enemy.

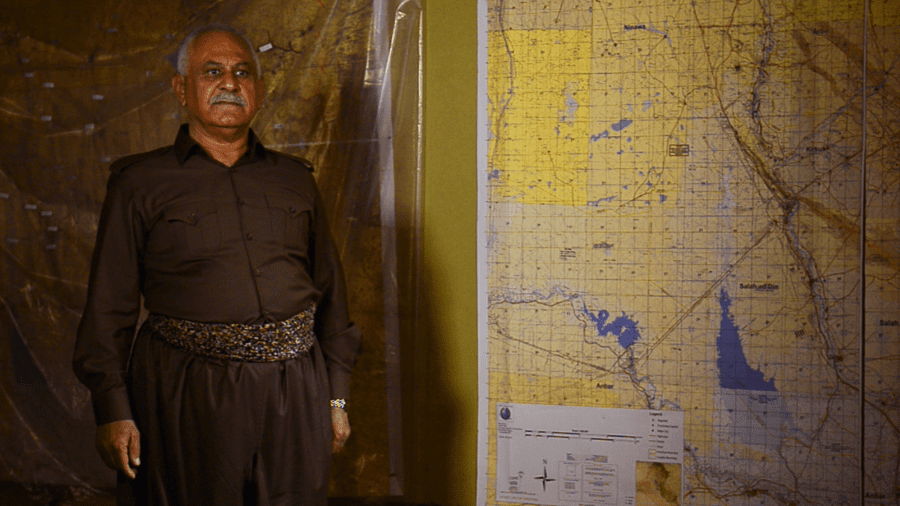

SHEIKH JAFFAR MUSTAFA was a leading PUK military commander at the time of the 1986 attack on the city of Kirkuk.

PUK and Iranian attack on Kirkuk provokes Iraqi wrath

On 10 October 1986 the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) combined with Iran to launch a joint military offensive on Kirkuk, Iraq’s economic core and one of the richest oil reserves in the entire country.

The PUK side of the operation was led by Nawshirwan Mustafa, then deputy secretary general of the party. In his memoirs, he writes the attack was designed to cripple the Iraqi economy and with it the Ba’athist regime.

Iranian film crews recorded the military operation and broadcast reports from the battlefield on IRIB, the Iranian national TV network. Despite being largely unsuccessful, the propaganda value of such a bold military incursion in Iraq was great to the Iranians. However, the blowback from the attack would be costly for the Kurds.

‘We were the ones who paid a heavy price,’ says Sheikh Jaffar Mustafa, a leading PUK military commander at that time. ‘I think two oil wells were destroyed. The Iraqi regime retaliated. They destroyed the villages, expelled the Kurds and brought in Arabs in their place. It was beyond a mistake.’

Immediately after the attack, the PUK signed an agreement with the Iranians setting out the terms of their military, political and economic cooperation. Saddam Hussein viewed this accord as a gross betrayal.

Between 1987 and 1989, SADDAM HUSSEIN gave his cousin, ALI HASSAN AL-MAJID, special powers to use the full apparatus of the Iraqi state – military, security and civilian – to destroy rural Kurdistan and ‘slaughter the saboteurs’.

‘Chemical Ali’ instates a ruthless programme of genocide in the 1980s

In late 1986 the Iraqi army only controlled Kurdish cities, larger towns and main roads. Meanwhile, Kurdish guerillas representing different parties moved freely through the rural areas of Kurdistan.

Angered by the Kurdish resistance, Saddam Hussein appointed Ali Hassan al-Majid as head of the Ba’ath Party’s Northern Bureau ‘to solve the Kurdish problem and slaughter the saboteurs’. ‘Chemical Ali’, as al-Majid would become better known, oversaw the Iraqi regime’s first chemical bombing of the Kurds in the Jafati and Balisan valleys in April 1987.

It was an extraordinary step, taken with complete disregard for international law, and is one of the few times in human history that a sovereign state had used poison gas against its civilian population.

This attack was soon followed by two directives issued by al-Majid in June 1987. The first applied a shoot-to-kill policy for any person found in areas decreed to be prohibited. The second ruled that Kurds aged between 15 and 70 captured in the prohibited zones could be lawfully executed.

On 6 September 1987 al-Majid chaired a meeting with his Northern Bureau that ordered a national census in the prohibited zones, with the policy to be administered by the Revolutionary Command Council.

It was to take place on 17 October. Up until that date Kurds were invited by al-Majid to rejoin the fold of Ba’athist Iraq.

In practise, however, al–Majid did not send any government officials to register Kurds in prohibited areas. Furthermore, his June directives – in particular, order number 4008 – instructed that Kurdish villagers caught travelling to or from the prohibited zones were to be executed by agents of Amn, the Iraqi secret police, or army soldiers. This meant any person in an area deemed to be prohibited could be lawfully killed for attempting to register themselves in a city.

The bureaucratic absurdity of this situation, coupled with its lethal implication, was typical of the logic that ruled Saddam Hussein’s Anfal campaigns.

President of Iraq SADDAM HUSSEIN shakes the hand of ALI HASSAN AL-MAJID, then Minister of Defense, after the 1991 collapse of the Kurdish uprising in the immediate aftermath of The Gulf War.

Image: Iraqi state television

The Pattern of Anfal

Between 1987 and 1989 Saddam Hussein granted Ali Hassan al-Majid further powers that allowed him to devote the Iraqi State’s military, security and civilian apparatus to destroying Kurdish villages. Those who had supported the Kurdish resistance were targeted.

Each of the Anfal military campaigns organised by al–Majid was slightly different in nature, yet each aimed to break both the resistance of the Kurdish peshmerga fighters and the village networks that sustained them.

The overall pattern of the operations was consistent, however. First, rural Kurdish settlements were targeted by the Iraqi air force, who used Russian Sukhoi fighter jets to drop chemical weapons onto both civilian and peshmerga targets. These air raids were frequently accompanied by blitz attacks on Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) or Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) bases nearby.

Second, ground troops from the Iraqi army, accompanied by pro-government Kurdish militias known as jash, encircled targeted areas and destroyed all human habitation. They looted possessions and farm animals, set fire to homes, and then sent in bulldozers to complete the demolition.

Third, fleeing Kurds were captured and loaded onto waiting convoys of trucks, which transported them to holding centres and transit camps. Afterwards, jash forces were sent back to sweep up any remaining escapees. The Iraqi secret police then combed villages and towns for fugitives, luring them with false promises of amnesty.

It was a grotesque process that was devastatingly effective.

SADDAM HUSSEIN launched the al-Anfal operations against rural Kurdistan with a wave of attacks on PUK targets in the Jafati valley, the first of eight major military campaigns in 1988.

First Anfal takes place in the Jafati valley, 23 February to 19 March 1988

Ali Hassan al-Majid sought to demonstrate to the Kurds that the Iraqi army could prevail over peshmerga wherever it chose, and, according to the Iraqi propagandists, ‘cut the head off the snake’.

With the First Anfal campaign his forces targeted the main headquarters of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), northeast of Sulaimaniya. Aside from the PUK political bureau, the base contained the party’s main field hospital, a prison, a radio station and a newspaper printing press, all of which were scattered across neighbouring villages.

The villages of Bergalou, Sergalou, Haladin and Yakhsamar, hidden away in the rugged Zagros mountains, were classic guerrilla strongholds. They lay close to Dukan’s strategically important hydroelectric power station and dam, which supplied the cities of Sulaimaniya and Kirkuk with water and electricity.

However, despite being a well organised and efficient fighting force, some military experts believe the PUK made a strategic mistake by establishing their headquarters in the Jafati valley. Although well positioned to withstand attacks with conventional weapons, it was especially vulnerable to chemical attacks in which bombs exploding on mountains slopes sent poison gas cascading down onto those below.

In the early hours of the morning of 23 February 1988 the Iraqis attacked from all directions, catching PUK peshmerga fighters unawares. Tanks and jets with chemical weapons payloads pounded the villages of Challawa, Chokhmakh, Gwezeela, Haladin and Yakhsamar, as Iraqi forces advanced on the PUK’s military bases in Bergalou and Sergalou.

The front line of the Iraqi offensive stretched for a full 40 miles from Bingird, a settlement close to the eastern shore of Lake Dukan, and then south-east towards the towns of Mawat and Chwarta, just north of Sulaimaniya.

The fighting would continue for several weeks.

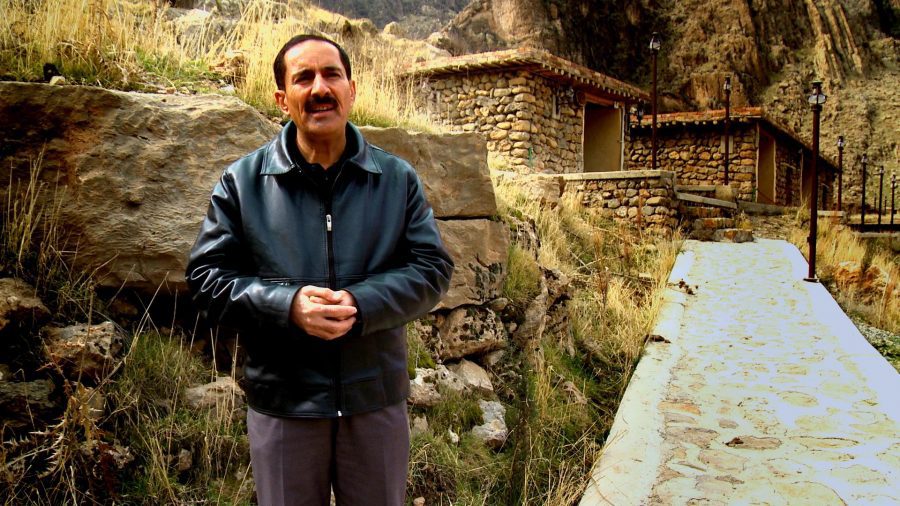

ABDULKARIM HALADINI was a political strategist at the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) headquarters in the Jafati valley. The base consisted of hospitals, a media centre that ran a radio station and cultural events, and a printing press that produced Kurdish newspapers. All were destroyed in a massive Iraqi chemical attack in 1988.

‘The Iraqi army fired 650 chemical shells at Bergalou in one day’

The PUK had been warned of the potential for an attack. Previously, the Iraqis had attacked the PUK’s headquarters from the air with conventional weapons and the party had also received intelligence that the Ba’athists were planning to use poison gas should they ally with the Iranians.

However, the sheer scale of the Iraqi attack and its boldness caught the PUK peshmerga by surprise. The Iraqis had assembled 150,000 soldiers and one thousand tanks behind the mountains, and attacked with heavy artillery and chemical weapons.

Abdulkarim Haladini, a peshmerga and political strategist with the PUK based in Sergalou and Bergalou witnessed the attacks firsthand.

‘The Iraqi army fired 650 chemical shells at Bergalou in one day,’ he says.

Despite being massively outnumbered and outgunned, PUK peshmerga held out for over three weeks against the Iraqi army, air force and elite Republican Guards.

Peshmerga and Kurdish civilians in the Jafati valley were forced to flee across mountains following attacks in the First Anfal campaign. The route was perilous and many were exposed to extreme cold.

PUK tells Kurdish villagers to flee towards Iran

With weather conditions harsh and snow falling heavily, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) fighters grew increasingly demoralised and were ordered by their leaders to withdraw.

‘After heavy fighting we realised the battle between the peshmerga and Ba’ath forces was one sided as we only had simple weapons,’ says Abdulkarim Haladini, a PUK peshmerga.

By this time the Iraqi army was enveloping the Jafati valley on three sides, leaving only one realistic escape route: across the Zagros mountains towards the Iranian border.

Realising there was little they could do to protect civilians, PUK peshmerga told villagers to take their chances on their own.

The people were well prepared for this course of action. Prior to the Anfal campaigns, the PUK had frequently broadcast warnings of incoming attack, and these warnings are likely to have saved hundreds of lives.

Large numbers of villagers from the areas under attack, which included Bergalou, Challawa, Chokhmakh, Gwezeela, Haladin, Kanitu, Margeh, Sedar, Sergalou, Sharsten and Yakhsamar, fled towards Iran. They were pursued by Iraqi soldiers and jets.

JAWAHIR HASSAN AHMAD fled her village of Haladin after the Iraqi army bombed the Jafati valley with chemical weapons in 1988. Her son could not walk so she pulled him along on a blanket while others were forced to leave their children behind. In Iran they were once again attacked with poison gas.

‘We didn’t know what chemical weapons were but soon we realised we couldn’t breathe’

Two days after the attack on the PUK headquarters in Bergalou, the Iraqi airforce bombed the village of Haladin with chemical weapons. Haladin was a special target for the Iraqis, whose intelligence told them Iranian soldiers were based nearby. Jawahir Hassan Ahmed was there.

‘The Iraqi forces attacked the Iranian soldiers using missiles and a huge number of Iranian soldiers were killed,’ she says. ‘After that happened we all fled our village.’

The villagers of Haladin were forced into the Zagros mountains through blizzards to seek sanctuary in Iran. Conditions were so bad that some even abandoned their own children.

‘They could do nothing for them,’ says Jawahir.

She saved her own son, Sardar, by wrapping him in a blanket and dragging him through the snow. Together they reached Shanakhsei village where they were picked up by Iranian military trucks and driven across the border to Baneh, just inside the Iranian border.

JAWAHIR HASSAN AHMED was forced to flee her home village of Haladin during the First Anfal in the Jafati valley. She arrived at a refugee camp in Baneh, Iran that was also attacked by the Iraqis with chemical weapons.

Chemical bombs in the Jafati valley cause massive refugee exodus

The Iraqi forces were relentless in their pursuit of Iraqi Kurds even on Iranian territory. Shortly after Jawahir Hassan Ahmed arrived in Baneh, Iran, Iraqi jets attacked the nearby Hawara Khol refugee camp with poison gas.

Jawahir lost one of her five children in the chemical attack and her brother was taken and never seen again. In all, more than 60 people from Haladin disappeared during Anfal.

The majority of adult villagers bombed in the Jafati valley survived the First Anfal. But they lost their property and possessions in what became Iraq’s largest refugee exodus since the 1975 collapse of the Barzani revolt.

Those carrying children were especially vulnerable as they fled their home villages. They could not move quickly and were in some cases running through snow without shoes.

One of the most tragic stories of this chaotic exodus involved the inhabitants of the village of Kanitu, who panicked when they heard – wrongly – that the Iraqi army was nearby.

They fled across the Kalki Kanitu mountains, the most dangerous route possible, where they were exposed to extreme cold. Here, many villagers slipped on the icy ground of a frozen mountain pass and fell to their deaths.

With the Iraqi army gassing refugees in March 1988, KHIDIR MUSA MOHAMMED AMIN fled in panic towards Iran across the mountains. He walked for hours through blizzards and subzero temperatures without noticing that his nephew, whom he was carrying on his back, had frozen to death.

‘Our bodies were freezing and icicles hung from our faces’

‘Our bodies were freezing and icicles hung from our faces,’ says Khidir Musa Mohammed Ameen, who moved slowly from Kanitu with his two sisters, brother-in-law and four sons up into the Kalki Kanitu mountains.

He carried one of his nephews, Hunar, on his back across chasms and slippery mountain passes. Visibility was poor and it was bitterly cold. Yet the foggy conditions meant he felt safe from the Iraqi army, which he believed was in the valley below.

Over the course of the day, the treacherous conditions slowed their progress and the cold took its toll. Khidir’s companions drew his attention to the small boy on his back.

‘He’s been dead for nearly four hours,’ one said. Khidir wanted to carry his nephew’s corpse with him to Iran but was persuaded to leave the boy behind in the mountains. He laid the body to rest in a cave with those of four or five other young children who had also died of the cold.

Khidir reunited with his brother-in-law in a hut where they found shelter. By this time he had witnessed his sister die of hypothermia along with many other scenes of horror caused by avalanches and extreme cold.

Ten years after the crippling 1988 attack on Halabja by the Iraqi army, a British television team visits the city to investigate the long-term effect of chemical weapons on its inhabitants. They find a tragedy that has not only escaped the notice of the outside world but also the Kurds themselves.

Away from Anfal: catastrophe in Halabja on 16 March 1988

For several weeks the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) resisted the Iraqis’ poison gas onslaught against their headquarters in Bergalou and Sergalou. As part of a counter offensive, their forces joined the Iranian attack on Halabja, a Kurdish city close to Iraq’s border with Iran.

Iraqi intelligence reported a mobilisation of large numbers of peshmerga and Iranian Revolutionary Guards to the west of Halabja, and on 13 March 1988 Iran officially announced the operation. Expecting the Iraqis to use gas in the defence of the town, the Iranians equipped their soldiers with protective masks.

By 15 March Iranian soldiers had swamped the city and were openly celebrating its ‘liberation’ although Kurdish citizens of Halabja were more apprehensive.

The Iraqi retaliation was immediate and merciless. On 16 March Ali Hassan al–Majid’s forces bombarded Halabja with napalm, heavy artillery strikes and massive poison gas attacks that turned the city into an enormous concrete graveyard. Some 5,000 people died and 10,000 were injured in the attack.

Saddam Hussein’s savage response demonstrated he was ready to kill on an unprecedented scale to destroy those who threatened him.

More than 5,000 people died after the Iraqi’s chemical attack on Halabja and a further 10,000 were injured.

More than 5,000 people die in Halabja

Despite being the single greatest atrocity of Iraq’s war against the Kurds, Halabja was not considered by the Iraqi regime to be a part of the Anfal campaigns against rural Kurdistan. This was because it was an operation of the Iran–Iraq war.

What it did reveal, however, was the Ba’ath Party’s complete disregard for civilian life. This would continue throughout their Anfal campaign against rural Kurds. In each of the eight phases of Anfal, chemical weapons were used against Kurdish civilian communities and peshmerga fighters with no distinction drawn between the two.

The aim was to break the Kurdish spirit. Saddam Hussein wanted to spread terror and let Iraq’s Kurdish population know that if they offered any further resistance they risked mass slaughter.

Days after the bombing of Halabja, the PUK headquarters in Sergalou fell on 18 March and Bergalou 19 March. That same day, the Iraqi army issued a statement declaring victory, containing the first official reference to their campaign as an ‘Anfal operation’.

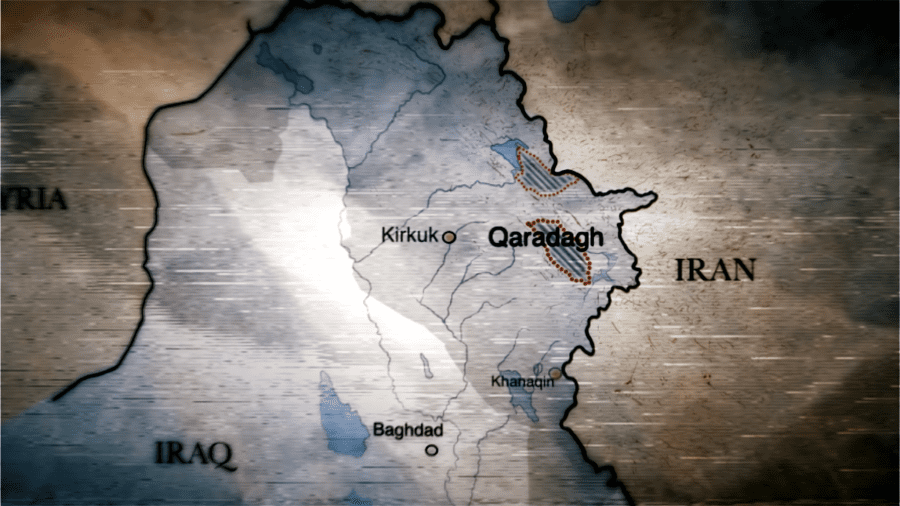

The Second Anfal began with the lethal 22 March 1988 chemical weapons attack on Sewsenan village in the Qaradagh region of northern Iraq. Qaradagh was a major hub of PUK activities in the governorate of Sulaimaniya.

Second Anfal strikes PUK in Qaradagh, 22 March to 1 April 1988

After the fall of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) headquarters in the Jafati valley, the Iraqi army turned their attention to the PUK’s regional command in the Qaradagh region – a locus for PUK activities in the governorate of Sulaimaniya.

Since 1983, the hubs of peshmerga activity in Qaradagh had been the villages of Sewsenan, Takiya and Balagjar, with the latter two villages sheltering the armed forces of both the PUK and the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP). The PUK had established a field hospital nearby, in an area that was unmarked on Iraqi maps.

Other peshmerga from the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Kurdistan Islamic Movement had also been harboured at Takiya and Balagjar.

In early 1988, Iraqi intelligence cables reported that soldiers of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard had passed through peshmerga camps in the Qaradagh region. Iraqi jets subsequently dropped poison gas bombs on Takiya and Balagjar in February. The peshmerga were prepared though, evacuating local villagers in advance of the attacks, and so there were no fatalities.

However, their preparedness was no defense against the Iraqis’ lethal chemical attack on the village of Sewsenan on 22 March 1988. Ali Hassan al-Majid’s Second Anfal operation against the Kurds had begun.

AHMED QADIR MAJID was one of the first to arrive at Sewsenan village after it was gassed in 1988. He found the bodies of his sister, her husband and their children at their house and buried them early next morning. He lost 11 members of his family in that attack.

‘We didn’t want to leave them behind for the dogs to eat’

The attack on Sewsenan village took place on 22 March 1988. It was one day after Newroz, the Kurdish New Year, and less than a week after the Iraqi military’s massive attack on Halabja.

Sewsenan, which lies 30 km south of Sulaimaniya and also served as a PUK base, was attacked at sunset with nerve agents and mustard gas. The Iraqis had timed the attack to kill families who were gathered together for their evening meals and also those conducting their evening prayers in the local mosque.

It became clear this was not a normal attack when clouds of smoke billowed in the air. Villagers heard the whistling sound of shells in the air and could smell an odour many described as being ‘like rotting apples’.

Ahmed Qadir Majid was the first person to arrive at Sewsenan in the aftermath of the bombing and witnessed a scene of devastation. He found the bodies of his relatives who had died as they tried to escape the toxic fumes.

‘We didn’t want to leave them behind for the dogs to eat,’ says Ahmed. ‘With the help of other villagers we dug graves for them that night and buried them early next morning.’

TAHA MOHAMMED AMIN was 12 when the Iraqis gassed his home in the small town of Sewsenan. When his father returned from the mosque he saw his children dying before dying himself. Taha now works as a caretaker at the local cemetery so he can be close to where his family is buried.

‘It’s like an awful nightmare: people being gassed, houses burning down’

Taha Mohammed Amin was just 12 years old when the Iraqis gassed Sewsenan.

A bomb exploded outside his house, split in two and sent a cloud of white smoke into the sky. He remembers its ‘nice smell’ and then the animals quartered below the house collapsed and died in their stalls. Then young children began to die.

His father returned from the mosque and saw his children’s bodies on the ground. ‘He started crying and moving them around,’ says Taha. ‘Then he died himself.’

Taha’s brother became dizzy and began to bleed from both nostrils. He walked around in circles in the yard outside and then collapsed. Another brother also bled from the nose and screamed in pain. Taha tried to get him onto the roof. ‘Then I felt dizzy myself and became unconscious,’ he says.

Neighbours left their houses and became affected. Five of Taha’s family were killed by the gas. Even today, he cannot escape the trauma of what happened.

‘It’s like a nightmare, an awful nightmare,’ he says. ‘It appears when I go to bed: people being gassed, running around… houses burning down, people surviving and not surviving.’

Sewsenan cemetery contains the graves of 68 rural Kurds who died in the Second Anfal. In the days after the attack on Sewsenan the villages of Dukan and Jafaran also suffered poison gas attacks.

23 and 24 March: further chemical attacks on Dukan and Jafaran

In Sewsenan cemetery lie 68 graves of villagers who died in the Second Anfal chemical attack on the village. Taha Mohammed Amin is the caretaker for the local cemetery, where all the members of his family he lost that day are buried.

‘I come every day,’ he says. ‘It gives me relief because it feels like I’m with them.’

The bombing of Sewsenan was just the first attack of the Second Anfal, however. The following day, 23 March 1988, the Iraqis dropped poison gas in Qaradagh once again, this time attacking a Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) base in Dukan, a village containing around 70 houses.

The following day, the Iraqi army targeted Jafaran, a small farming village that was the location of the regional headquarters of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), which controlled their operations in the governorate of Kirkuk.

Fortunately the village was deserted after it had been bombed by the Iraqis the previous year, so there were no casualties, although many farm animals were killed.

After three days of relentless chemical attacks in the Second Anfal, villagers from Sewsenan (pictured) and other rural settlements in the Qaradagh region fled north seeking sanctuary in the city of Sulaimaniya.

Civilians in Qaradagh flee chemical attacks

After three days of relentless chemical attacks, fleeing Kurdish villagers were in a state of panic. The Iraqi army began their ground assault on 23 March, and their soldiers, supported by ‘jash’ Kurdish collaborators, converged from four directions around the targeted villages.

Afraid of what might happen if they were captured and with no other route of escape available, there was a mass exodus as the afflicted villagers headed north in search of sanctuary in Sulaimaniya.

Initially, Iraqi soldiers processed Kurdish civilians in a far less systematic manner than would become customary in later stages of Anfal, and so many villagers were able to escape to Sulaimaniya via the central highway linking the city with Qaradagh.

Some survivors of the Sewsenan attack even heard rumours of a temporary amnesty, so waited by the side of the Qaradagh mountains to meet the Iraqis.

By the fifth day of the attack, however, Iraqi soldiers were manning the checkpoint on the highway to Sulaimaniya and began to arrest people en masse.

Those who were arrested were loaded onto trucks and transported to a military base in Sulaimaniya that was being used as a prison camp. Their names were recorded and their valuables and identity documents were taken.

TOOBA HAMID RASUL, from Nowti village in the Qaradagh region, was separated from the rest of her family after a poison gas attack. She was captured by the Iraqi army, but jumped from a military lorry with her baby tied to her back. Tooba escaped to Suleimaniya and was reunited with her family after Anfal.

‘No one heard me jump from the lorry because of all the screaming’

Tooba Hamid Rasul is a native of Nowti village. Her daughter, Saada, died in the bombing of nearby Jafaran. In the panic, with clouds of poison gas still visible in the air, Tooba became separated from her husband Haji but found Saada’s body. She picked it up, put it in the back of a relative’s truck and drove away in another vehicle with her nine-month-old baby.

Tooba later buried Sa’ada by the roadside. Her car was stopped by the Iraqis and she and the other passengers were captured. They were then loaded into the back of a crowded army vehicle driven towards Sulaimaniya.

Tooba, who was carrying her baby on her back, feared she and her fellow captives were being bussed to a certain death. So she jumped from the moving truck, holding her baby in her hands to cushion the fall.

‘No one was aware of me jumping off because of all the yelling and screaming,’ she says.

Somehow she landed safely on the road and her baby was unhurt. Tooba picked herself up and ran with her baby until she reached Waluba village. She had relatives there who welcomed her into their house and then helped smuggle her into Sulaimaniya.

Following the Second Anfal in the Qaradagh region (pictured) and the Third Anfal in Garmiyan, the Iraqi army attempted to destroy all traces of human settlement in the ‘prohibited zones’ established by ALI HASSAN AL-MAJID.

The Third Anfal blitzes Garmiyan, 7 to 20 April 1988

By early April, the remnants of Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) peshmerga had fled south from the Second Anfal to PUK strongholds in the Garmiyan region. There, Kurdish PUK forces adopted a defensive position at the village of Sheikh Tawil, an area that had received many refugees from the Qaradagh region.

Garmiyan was a political heartland of the PUK revolt, but its flat terrain was less conducive to guerrilla warfare than the Jafati valley and Qaradagh. Furthermore, the party’s bases were not fortified. The Iraqi army would ruthlessly exploit these vulnerabilities.

On 7 April 1988 the Third Anfal began with an attack on Tuz Khurmatu.

The sheer scale and ferocity of the assault shocked the PUK peshmerga. The Iraqi army easily cut off their supply lines, leaving isolated PUK fighters the choice of fleeing or fighting until they ran out of bullets. After the carnage of the First and Second Anfals, and following news of the devastation at Halabja, there was an inevitable collapse in morale amongst the peshmerga.

The Iraqi army used pincer movements to channel fleeing villagers towards collection points throughout the Garmiyan region.

Iraqi army closes in on PUK peshmerga and civilians

Iraqi reports from the battlefield revealed that military commanders had orchestrated a comprehensive series of pincer movements on villages and peshmerga positions. In each case Iraqi troops encircled villages, channelling fleeing civilians towards nearby collection points.

The overwhelming concentration of Iraqi troops and militia gave the Kurdish villagers from Garmiyan almost no prospect of escape. Fugitives were pursued into the mountains and cities, either by foot or by helicopter.

In the process the Iraqis destroyed all traces of human settlement, amply fulfilling Ali Hassan al-Majid’s 1987 demand for a bombardment of the Kurds that would ‘kill the largest number of people present in the prohibited zones’.

The Iraqi pincer campaigns centred on three separate areas.

The Iraqis arrived in south Garmiyan at Tuz Khurmatu on the morning of 7 April, progressed to the villages of Warani Upper and Lower and then moved on to Tazashar, a PUK strategic base where peshmerga put up a staunch defence before they were encircled. Witnesses reported a chemical weapons attack on the base, followed by the destruction of villages including Kani Kurda and Shekh Hamid, and the final peshmerga defensive position at Karim Bassam.

PUK peshmerga had been forced into a defensive retreat by the time of the Iraqi army’s Third Anfal campaign. Where possible they defended villagers in Garmiyan and helped them escape, but the scale and ferocity of the Iraqi attacks was overwhelming.

Iraqis raze clusters of villages in southern Garmiyan

A second column of Iraqi troops targeted Sangaw, also in southern Garmiyan, and destroyed clusters of villages: Banamurt, Dar Baru, Darawar, Darzila, Drozna, Dubirya, Hanjira, Hasan Kanush, Hasan Kanush Upper and Lower, Kalaga Kareza, Kelabarza, Segomatan and Tappa Arab.

Hundreds of villagers were captured and trucked away. Surviving peshmerga were driven up into the Qaradagh mountains, where they were met by other Iraqi units who began to shoot at them.

On 10 April the Iraqis led a two day siege against peshmerga in Omar Bil, forcing them to retreat, and then demolished 20 other villages and a PUK base at Tukin. On 11 April they took Duraji and also the villages of Balakai Kubra and Balakai Sughra, inhabited by members of the Daoudi tribe.

Tilako Big and Tilako Little were razed along with other villages including Baraw, which was inhabited by the Jaff, one of the tribes that lost the most people during Anfal.

The Iraqi troops destroyed the village of Kulajo on 13 April before moving onto Hawara Barza, Kuna Kotr, and finally Qulijan.

In April 1988, during the Third Anfal, the Iraqi Army arrested ASMAR MOHAMMED JABAR together with other villagers fleeing the bombardment of Mahabaram. She went into labour by the side of the road in the cold, wet spring weather.

‘We had nothing but a used razor to cut the umbilical cord’

With news of the nearby Iraqi army attacks quickly spreading, Asmar Mohammed Jabar, who was nine months pregnant, drove away on a tractor with other women and children from Mahabaram aboard.

They were soon stopped at an army checkpoint near Qaratamur village and told by Iraqi soldiers to disembark. Their tractor was confiscated and in heavy rain they were moved into an open field along with hundreds of fleeing villagers.

There was no shelter nor food. At about 7pm, in great pain, Asmar went into labour. The soldiers refused to let her brother fetch a blanket and clothes from the tractor. Women from the village formed a circle around Asmar to shield her for the next 15 or 16 hours as she delivered her baby.

‘When the baby was born we had nothing to cut the umbilical cord with,’ says Asmar. ‘My brother had a used razor in his pocket. He was worried the baby might get an infection but we had no choice.’

‘They placed the baby in my arms and it began to shiver even more than me,’ she says.

On the third day they were moved to Topzawa prison camp near Kirkuk where the men and older boys were separated from the women and younger children. These male prisoners were never seen again.

The strategy of the Iraqi army was to funnel fleeing Kurdish villagers towards collection points, from which they would be transported to prison camps for processing. In South Garmiyan, they were collected at a youth centre in Tuz Khurmatu and a Soviet-style fort at Qoratu (pictured).

Iraqi army completes Third Anfal operation within Garmiyan

In northern Garmiyan, the Iraqi army devastated villages near the area of Qadir Karam after 10 April 1988, many of which were inhabited by the neighbouring Zangana and Jabari tribes. They encountered little resistance, as word of the chemical attack on Taza Shar had spread. The Anfal operations then continued in Hanara, where there were few peshmerga, and on to other Zangana villages including Qaitwan, Qaitul and Qircha.

By April 20, the Iraqi forces had completed their missions having destroyed every Kurdish village in Ali Hassan al-Majid’s ‘prohibited zones’ of Garmiyan. The peshmerga at Shekh Tawil had been subdued, along with the last PUK base at the foot of the Zarda mountains.

By the Third Anfal, the bureaucratic machinery of Ali Hassan al-Majid’s combined forces – party, police and intelligence agencies – moved into a higher gear: Kurdish civilians were rounded up, processed and then executed with ruthless efficiency.

Fleeing Mahabaram village after it was attacked by the Iraqi army in April 1988, SEMEN KARIM RAZA and her seven children were arrested in Qaratamor and taken to Topzawa Prison. At Topzawa, men were separated from women, children and the elderly. Semen describes the last moment she locked eyes with 15 men from her village before they were taken away.

‘Prison guards took children from their mothers and said they would behead them’

Semen Karim Raza, of Mahabaram village in Garmiyan, was captured on the road to Chamchamal as she fled Anfal. Iraqi soldiers put her family on buses and drove them to Topzawa prison camp, on the outskirts of Kirkuk.

At Topzawa male villagers, including her husband, were separated from the women and children. Semen watched through the prison window as guards tied his hands behind his back with his headscarf, and he returned her gaze, his eyes bereft of hope. There were about 15 other male villagers with him.

‘They were looking at us through the window of the prison,’ she says. ‘We never saw them again.’

After spending time in Topzawa, Semen was taken to the women and children’s jail in Dibs, where conditions were slightly less harsh. But the camp was hit by a measles epidemic which spread rapidly and with no medical help offered the women were unable to treat their children.

‘Maybe 50 children died in one day,’ says Semen. ‘Their skin became dry and they died. One woman had three children with her, all died…. One of mine died as well. My three sisters were in jail there and each of them lost a child.’

Semen spent six months in captivity at Dibs before being taken south to Tikrit. There she was freed after the Iraqi government offered Kurdish prisoners an official amnesty.

After being processed by Iraqi forces during the Third Anfal, many women, children and elderly men were transported to Nugra Salman (pictured), a notorious prison camp in the southern Iraqi desert near the Saudi Arabian border. A large number of them died here of neglect, starvation and disease.

Iraqi soldiers capture fleeing villagers, bus them to processing centres and execution sites

The strategy of the Iraqi army was to funnel fleeing Kurdish villagers towards collection points, from which they would be transported to prison camps for processing.

In northern Garmiyan, villagers were transported by both military and civilian buses to collection points in Laylan, Aliawa, Qadir Karam and Chamchamal. In South Garmiyan, they were collected at a youth centre in Tuz Khurmatu and a Soviet-style fort at Qoratu.

In Chamchamal, Kurdish locals spontaneously protested by throwing stones at the buses until Iraqi soldiers opened fire on the crowd. Some prisoners escaped in the chaos. A number of other fugitives were less fortunate: several found by Amn, the Iraqi secret police, were publicly executed; the Iraqi government even demanded that their families pay for the bullets that killed them.

Once collected at processing points, male villagers were separated and trucked to unknown destinations where they were almost certainly executed. Those who survived this selection process would be bussed to prison camps. In most cases this was to Topzawa, near Ali Hassan al-Majid’s military headquarters, although some were taken to Tikrit.

From Topzawa, women, children and some elderly men were sent to a prison camp in Dibs and then later to Nugra Salman, a fortress in the deserts of southern Iraq. Male prisoners were also incarcerated in this fortress, where many thousands died of neglect, starvation and disease.

Rural Kurdish males who were captured by the Iraqi army during the Anfal campaigns were frequently transported to sites where they were executed by firing squads and buried in the ground. The Iraqi government of SADDAM HUSSEIN was extremely secretive about the locations of these mass grave sites, and many remain undiscovered to this day.

Iraq’s ‘Anfalisation’ of Kurdish prisoners follows blueprint of Nazi Germany

For many, Anfal evokes Nazi Germany’s ‘Final Solution,’ a programme to exterminate European jews between 1942 and 1945. Yet Ali Hassan al-Majid’s method of executing Kurds more closely resembled that of the Nazi Einsatzkommandos, who operated mobile killing units in eastern Europe throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Adult men and teenage boys were lined up in pre-dug mass graves or forced to lie in trenches amidst fresh corpses, and then machine gunned where they stood. No notice of their death was given to relatives, who would say their loved ones had been ‘Anfalised’.

In most cases women and children were imprisoned in filthy, squalid conditions for months or even years. However, in the Third Anfal huge numbers of women and children were also abducted and never seen again. The criteria for their treatment seems not to have just been the location of their birth – which classified them as being residents of ‘prohibited zones’ – but the place where they had been taken prisoner.

It appears women and children captured in locations where there had been staunch peshmerga resistance were much more likely to be taken away and shot dead by execution squads.

MAHROOB MOHAMMED NAWKHAS was praying in Kulajo village when her daughter shouted Iraqi soldiers were invading. She fled with her husband and five children, leaving two sons to look after livestock. But they were captured and imprisoned in Topzawa. Men were isolated and never seen again: Mahroob’s husband was taken, and her son and daughter died in captivity.

‘“Do you want the wolf to eat you too?” said the prison guard in Topzawa’

Mahroob Mohammed Nawkhas still has vivid, painful memories of losing her husband and children after the Third Anfal. A native of the village of Kulajo, Mahroob was captured, along with her husband and five children, by Iraqi army officers in green uniforms and taken to Topzawa prison.

‘My husband was ill and didn’t have a single Iraqi dinar on him,’ she says. ‘They didn’t even let us say goodbye.’

The families were told by the Iraqi soldiers that their men would be enlisting in the army to fight ‘the nation’s enemies’ and that they would be treated well. Yet Mahroob quickly realised just how grave the situation was. When vehicles arrived for the male villagers, her attempts to find out where the Iraqi officers were taking them were rebuffed.

‘The officer said, “Do you want the wolf to eat you too?”’ she says. ‘We lost hope.’

Mahroob lost 50 relatives during Anfal and half of Kulajo’s original 300 inhabitants are also missing. They are almost certainly lying in yet to be discovered mass graves.

‘I’d like to see their bodies being brought back home even though it renews our pain,’ Mahroob says.

The Iraqi army commenced their Fourth Anfal against rural Kurds with massive chemical weapons attacks on the villages of Askar and Goptapa in the Lesser Zab valley.

Fourth Anfal strikes the Lesser Zab valley, 3 to 8 May 1988

After the blitz of the Third Anfal, the remaining peshmerga forces retreated north: two groups went to Shwan, northwest of Chamchamal, while one other headed for the village of Askar, just south of the Lesser Zab valley.

While Ali Hassan al-Majid’s army planned its next attack, the Iraqi intelligence agencies set out to track down those who had slipped into anonymity in nearby towns or mujamma’a, the crudely built government resettlement camps.

In northern Garmiyan, many villagers escaped the Iraqi army dragnet and fled to Kirkuk and its surrounding towns. However, in southern Garmiyan villagers were hemmed in from all sides by troops, the surrounding mountains and an Arab populated desert. So few eluded their captors.

The rural Kurds captured by the Iraqis in this period, which included large numbers of women and children, accounted for the largest concentration of ‘disappearances’ in Anfal, with members of the Daoudi and Jaff tribes suffering by far the heaviest losses.

On May 3 the Iraqi military, buoyed by their decisive victory in the Fao Peninsula of the Persian Gulf in the Iran–Iraq war two weeks earlier, commenced a devastating chemical weapons attack on the villages of Askar and Goptapa to begin their Fourth Anfal campaign.

SAEDA OMAR RASUL relates how Askar was regularly attacked by the Iraqi army during the late 1980s. The village provided refuge to Kurdish deserters from the Iraqi army during the Iraq-Iran war. On one occasion she and other villagers were shot at by soldiers whilst surrendering. Later they saw Kurdish tribesmen who collaborated with the regime looting their homes.

Iraqi planes drop poison gas on Askar village and ‘birds fall from the sky’

The villages of Askar and Goptapa supported fighters loyal to the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) led by Jalal Talabani, but also had historic connections to the peshmerga of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) that dated back to the days of Mullah Mustafa Barzani.

Known as strong supporters of the Kurdish nationalist cause, Askar and Goptapa villagers suffered bombardments from the Iraqis throughout the 1980s and many would flee to the mountains at the first sign of trouble.

Saeda Omar Rasul wished she could have joined them. ‘I couldn’t go because I was pregnant,’ she says. ‘I’d already lost a baby running away from the last bombardment so we stayed at home.”

It was late afternoon and the village was ‘full of peshmerga and Iranian soldiers,’ says Saeda. Her brother-in-law urged her to hide in the mosque as he was suspicious of the way Iraqi planes were circling overhead. Only a few other women and children made it to the mosque in time.

As she ran, Saeda was aware of a pleasant smell ‘like apples.’ When people entered the door, they were already vomiting. A donkey had collapsed, birds were falling out of the sky, and cats were running around frenetically before dying.

After Askar village was gassed in May 1988, a heavily pregnant and starving SAEDA OMAR RASUL fled the village with her baby. She encountered a group of Kurdish irregulars attached to the Iraqi army. One of them gave her food, even though she spat at him in disgust for supporting the Ba’ath regime.

‘The jash had tears in his eyes: “You can curse me but you must take my food”’

Saeda Omar Rasul and the others fled in panic to the nearby Lower Zab river. At 3 am they were discovered by a jash unit patrolling the riverbanks. Saeda was certain they would be killed.

‘When one of them told me to give him my child, I accepted my fate and spat in his face. I said to him, “You bastards… You want me to give you my child? Never.”’

However, Saeda had misread the situation. The jash troops wanted to help them escape: they gave her bread and water, and new clothes. They also told the villagers what to tell the Iraqi officers at the nearby checkpoints to ensure their safe passage – that they were travelling ‘from Dukan on their way to Sulaimaniya’.

Despite the kindness of the jash, Saeda was still angry and cursed them for supporting the government. As she did so, she noticed one of the soldiers was in tears.

‘If it hadn’t been for the jash rescue, I am not sure we would have survived,’ says Saeda. The jash would later accompany them to Sulaimaniya and help them find their relatives.

The jash were Kurds who fought for the Iraqi government, frequently against Kurdish peshmerga. The word ‘jash‘ translates as ‘donkey’s foal’ in Kurmanji Kurdish and is considered a derogatory term. In this sense it is similar to the English word ‘quisling’, which is named for MAJOR VIKTOR QUISLING, the diplomat who ruled Norway for Nazi Germany between 1940 and 1945.

The jash – foes and occasionally friends

The jash, Kurdish collaborators who fought for the Iraqi government, played an ambiguous role throughout Anfal. They would act as advance scouting parties for the Iraqi military – or as cannon fodder.

After attacks they would comb the hillsides for fleeing villagers and bring those they found into custody. The jash would often lie to the predominantly Kurdish refugees, offering false promises of amnesty to trick them into surrendering themselves.

In many cases the jash materially benefitted from their actions. The Iraqi army would promise jash troops the possessions and even the wives belonging to the Kurds they captured.

In a 1992 interview with the American organisation Human Rights Watch, Muhammad Ali Jaff, a former jash collaborator, said an Iraqi army intelligence officer instructed him that, ‘The peshmerga are infidels and must be treated as such… their wives are lawfully yours, as are their sheep and cattle.’

There are few reports of jash fighters abducting female survivors of Anfal operations, yet the looting of abandoned villages was widely witnessed.

In spite of their reputation as traitors many jash aided the escape of Kurdish villagers throughout Anfal. Sometimes this clemency was borne of kindness and other times greed, as they would frequently demand bribes. In other instances, mercy was offered to those Kurds with whom they shared tribal or regional loyalties.

Several testimonies from those captured by jash forces in the Anfal campaigns suggest this was prompted by a late realisation of the Iraqi army’s murderous intentions towards rural Kurds. Many did not seem aware of the true implications of their actions.

This was almost certainly the case in Garmiyan, where several prisoners noticed their jash captors becoming upset at the processing centre in Tuz Khurmatu.

However, it is questionable whether the jash had any true power to avert the events of Anfal. In the operational hierarchy of Ali Hassan al-Majid’s campaign the jash militia were at the bottom of the pile, below foot soldiers in the regular army. Therefore, the promises they made to captured villagers were ultimately empty, even if they were made sincerely.

HAWRAZ RAFIQ KARIM tells how, after the chemical attack on Goptapa in May 1988, several families fled to the nearby Ballqamesh mountains. They hid in a cave but were discovered by Iraqi irregular forces and surrendered after a three hour battle His father, HAKIM REBWAR secured the release of the women and children at the cost of his own life.

Hakim’ Rebwar’s heroism at Ballqamesh mountain

Panic spread as the toxic cloud of poison gas drifted through Goptapa in the Fourth Anfal, but Hakim Rebwar, an experienced peshmerga, knew what to do. He grabbed his gun and led his fellow villagers towards a cave in Ballqamesh mountain.

The cave was big enough to hide them, but crying children in their party betrayed their presence to a couple of jash fighters patrolling nearby. The first entered the cave and was shot dead immediately but the second jash managed to alert his unit.

‘They called on us to surrender but we didn’t. We fought them to the last bullet,’ says Hakim’s son, Hawraz Rafiq Karim, a 14 year old boy at the time.

With no ammunition left Hakim presented himself to the Iraqis, stating he was the only peshmerga.

‘He said, “All the others are civilians and innocent,’ says Hawraz. ‘I don’t care what the consequences are for me. But no harm should come to them”.’

‘The jash told us they had never seen anyone as brave as my father,’ says Hawraz.

All the women and children were subsequently released. However, Hakim and other men from the group were taken away in an Iraqi helicopter. Hawraz would never see them again.

In advance of the Fourth Anfal, Iraqi forces opened the sluices at Dukan dam. This made it more perilous for villagers fleeing the chemical bombings at Askar and Goptapa to cross the Zab river.

Iraqi army occupies Lesser Zab valley, burns every village in ‘prohibited zone’

Prior to the chemical bombings of Askar and Goptapa, the Iraqis had opened the sluices at Dukan dam to prevent fleeing villagers from attempting to cross the Zab river towards the relative safety of Koysinjaq and Dukan.

Survivors subsequently fled in all directions: some went south to Chamchamal and others headed west parallel to the river into an area controlled by the Shekhan Shekh Bzeny tribe.

As in Garmiyan, the Iraqi army followed up their bombardment with an army dragnet, with over a dozen units enveloping the fleeing villagers from several directions at once. They encountered little resistance, although there were minor skirmishes with peshmerga on the slopes of Takaltu mountain and in the Chemi Razan valley.

By 4 May 1988 all resistance had been quelled following enormous civilian casualties, and within two days the area was under army control.

In the subsequent days the Iraqi army burned every village in the ‘prohibited zone’: north of the Zab river they destroyed Bogd, Kani Bi, Gomashin, Kani Hanjir, Kanirash, Klisa, Mela Ziyad, Satuqala, Qzlu and Xraba, and south of the river Ginaghaj, Grd Khabar, Jalamord, Mamisha and Qasrok were demolished, amongst others.

Throughout the Third and Fourth Anfals the Iraqi army captured fleeing Kurds and took them to processing centres, where adult and teenage men were separated and taken to execution sites. The majority of captives who were women, children or elderly continued as prisoners at Topzawa (pictured), where they suffered under filthy, squalid conditions for months and sometimes years.

Captured Kurdish males are taken from processing camps to Topzawa prison and then sent to execution sites

On 5 May 1988 the Fourth Anfal offensive turned west towards the village of Shwan, where peshmerga units from both the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) had bases. Helicopters and fixed wing aircrafts fired rockets to soften up the area for advancing ground troops.

Some villagers escaped to the hills, but many others were captured and several villages in the area destroyed.

The Iraqi army had identified Mamisha as an assembly point to which captured villagers could be funnelled before arrest.

They were taken to three holding camps in the Lesser Zab valley, which were located at Harmota, Takiya and Taq Taq. The latter was the largest and principal collection point for villagers arrested during the Fourth Anfal, where conditions were variously described as being akin to a cattle pen.

From here, the Kurdish detainees were loaded onto heavily laden military trucks and taken away to be processed at Topzawa detention camp near Kirkuk, after which they faced execution or further transportation to even harsher facilities.

On 15 May 1988 the Iraqi forces of ALI HASSAN AL-MAJID commenced the Fifth Anfal: chemical bombs hammered villages in the Rawanduz and Shaqlawa valleys, and the wave of attacks continued with the Sixth and Seventh Anfal operations, which ended in late August.

Fifth Anfal operation arrives in Rawanduz and Shaqlawa valleys, 15 May 1988

After four Anfal campaigns, the Patriotic Union (PUK) forces of Jalal Talabani had been driven from their headquarters in the Jafati valley, their mountain garrisons in Qaradagh, the flat lands of Garmiyan and from the Lesser Zab valley.

PUK survivors retreated towards the northern edge of the Dukan lake to make a final stand in the steep mountains close to the town of Rawanduz, just west of the Iranian border.

By the second week of May, the peshmerga reached the Balisan valley, the location of PUK bases in the villages of Bero and Tutma that controlled party operations in the Erbil governorate. Expecting another Iraqi siege, they gathered food and ammunition in nearby mountain caves.

The civilian population of the Balisan valley had mostly fled a year ago after the Iraqi army’s horrific 1987 chemical weapons attack. Some still lived in the village of Bileh, a remote spot which was regularly visited by PUK peshmerga, and also Ware, which lay right on the edge of Ali Hassan al-Majid’s ‘prohibited zone’ – close to a Iraqi government collective town, considered a safe haven.

The villagers of Ware were therefore surprised by the Iraqi airforce attack at dusk on 15 May 1988, not least because they were returning from preparations for Eid, the festival that breaks the fast of Ramadan. Nearby peshmerga units quickly recognised the threat when they saw jash forces lighting fires on the nearby mountain peaks. The bombings also targeted the villages of Nazanin, Kamusak, Aspindara, Aliawa, Smaquli Gali and Bana.

AISHA MAGHDID MAHMOUD witnessed the chemical bombing of Ware village in 1988. Panic-stricken villagers ran to the local spring to wash themselves and their children. However, the water was poisoned and 20 lost their lives. Unaware that Aisha, her brother and her mother had escaped, her father searched desperately for them in the village and never returned.

‘“Why my daughter?” she screamed, then fell face down and died’

A 12 year old on 15 May 1988, Aisha Maghdid Mahmoud was alone at home with her baby brother in Ware when the Iraqi planes flew overhead and dropped chemical bombs. Her father was guarding the sheep in the mountains and her mother was at the local spring washing meat for the evening meal.

Panic broke out when white smoke spread across the village and people began to drop dead. Aisha’s mother returned with her shawl soaked in water which she wrapped around her brother before they all fled to the spring. There, Aisha saw her neighbours throwing themselves into the water hoping that it would provide some protection.

‘When people jumped in they were poisoned,’ says Aisha. ‘There were about 20 dead people in that spring.’ Fortunately, her mother and baby brother were not amongst them. They were rescued by relatives from a neighbouring village, who carried them away to safety on mules.

Aisha’s father suffered a different fate though. Distraught, he ran back to Ware to search desperately for his missing family. Unaware that some had fled to safely, he searched through the corpses that now littered the streets of Ware before collapsing in shock.

Aisha says that the trauma of this day made him lose his sanity. He was soon reunited with Aisha in an Iraqi government collective town called Shkarta, but died a year later

Kurdish villagers in the Rawanduz valley were caught by surprise by the chemical bombings of 15 May 1988. Iraqi jets dropped bombs at dusk, when villagers were returning from preparations for Eid. With white smoke rising around them, villagers saw neighbours and family members drop dead as they became overwhelmed by the toxic gas.

Fifth Anfal resumes after a fallow week with multiple chemical bombings near Rawanduz on 23 May

There was relative calm for a week after the bombing of Ware, but chemical bombings resumed early in the afternoon on 23 May with multiple air attacks. Iraqi aircraft dropped poison gas on Balisan and Hiran, as well as villages in nearby valleys.

These included Faqeyan, Akoyan, Garawan, Malakan, Warte, Sheikh Wasan, Bileh, Nazanin, Seran and Rashki Baneshan.

In the early hours of 24 May Iraqi ground troops swept in from three directions, performing the now familiar ‘windscreen wiper’ style sweep used in other Anfal operations, as they moved clockwise and then anti-clockwise to close in on fleeing villagers.

Those who had not fled in anticipation of attacks ran to the hills, and most Kurds hurried towards the Iranian border. Some stayed in the mountains, however, while others sought sanctuary in the in mujamma’a complex of Hajiawa.

Villagers of Akoyan and Garawan in particular found shelter in Gulan. There, they were protected by the powerful tribal leader Swera Agha, himself a jash according to peshmerga intelligence, who ignored tribal differences by promising that he would protect any newcomers staying in his village from the demands of the Iraqi military. He was true to his word, although this put the lives of his own people at risk.

Lower Bileh suffered several civilian disappearances however, as Iraqi forces arrested survivors before transporting them to a processing centre in Spilk. Here their identities were recorded before the villagers were taken away in army trucks.

Fierce PUK peshmerga resistance at Korak mountain (pictured) contributed towards the Iraqis suspending hostilities between 7 June and 26 July 1988. The ceasefire gave civilians fleeing the rural areas targeted in the Fifth Anfal crucial time to escape into Iran.

Obstinate peshmerga resistance at Korak mountain stalls the Sixth and Seventh Anfals

Iraqi forces faced strong resistance from Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) peshmerga in the Fifth Anfal and the fighting in the mountainous terrain around Rawanduz continued on-and-off for a further three months.

The inconclusive nature of the operation was of concern to Baghdad: Ali Hassan al-Majid had anticipated that the PUK would be clinically dispatched in Rawanduz and Shaqlawa, allowing them to quickly move against Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) forces in Bahdinan south of the Turkish border. But this proved an optimistic assessment that did not anticipate the bravery of the PUK peshmerga.

Iraqi anxiety was raised further by the June visit of PUK leader Jalal Talabani to Washington D.C., where he spoke to senior United States government officials about Saddam’s genocide against the Kurds.

Peshmerga resistance around Korak mountain, coupled with the geopolitical uncertainty caused by Talabani’s Washington meetings, led to a temporary suspension of hostilities between 7 June and 26 July. This allowed most Kurdish civilians trapped in the battle zone enough time to escape into Iran across Qandil mountain. Consequently, the mass relocations and executions typical of earlier Anfal operations did not occur in the Fifth Anfal.

However, the tide turned against the PUK once again on 20 July, when Iran signed United Nations Security Council Resolution 598, which effectively ended the Iran–Iraq War. With the eight year war finally resolved, Saddam Hussein began to personally involve himself in the Anfal operations against the Kurds and focus all his military resources on ‘the Kurdish problem’.

The Sixth and Seventh Anfal operations targeted villages in the Balisan valley, the second time ALI HASSAN AL-MAJID had ordered Iraqi forces to strafe the area in a 15 month period. The previous 16 April 1987 attack was the first time in world history that a sovereign government had attacked its subjects with chemical weapons.

Sixth Anfal arrives on 26 July 1988, the Seventh Anfal on 30 July

On 26 July the Iraqi assault recommenced with the Sixth Anfal: a relentless chemical bombing attack on the valleys of Balisan, Malakan, Warte, Hiran and Smaquli Gali, which struck many of the villages previously targeted in the Fifth Anfal. The bombings and fighting continued for weeks.

Those civilians who remained were mopped up by jash forces. In Smaquli Gali valley villagers were told they would only be ‘pardoned’ if they handed over weapons. However, once they tracked down guns belonging to dead peshmerga or from weapons caches and handed them over, they were branded ‘peshmerga’ and forced to sign confessions. The unpleasant charade ended with the jash sending the villagers to Topzawa in army trucks, where they were imprisoned or killed.

On 30 July the Seventh Anfal began with a chemical bombing campaign on Balisan, Balokawa and Khate, with the aim of preparing the ground for the next major operation further north in the Bahdinan region.

The Iraqi chemical bombings, artillery attacks and troop incursions continued until 27 August 1988, when the remaining PUK peshmerga in the Balisan valley dynamited their headquarters. By 28 August the valleys of Rawanduz and Shaqlawa were under the full control of the Iraqi army and airforce.

The Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Anfals were the most complex operations of Saddam Hussein’s campaigns against rural Kurdistan, largely because of the fierce resistance of Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) peshmerga.

On 20 July 1988 Iran signed United Nations Security Council Resolution 598, demonstrating the Iranian leadership’s willingness to arrange a ceasefire with Iraq. With the eight year Iran–Iraq War finally resolved, SADDAM HUSSEIN began to personally involve himself in the operations against the Kurds and focus all of Iraq’s military resources on Bahdinan and their Eighth and Final Anfal.

Iraq marshalls a military fighting force in Bahdinan that hugely outnumbers KDP peshmerga

After the completion of the Seventh Anfal, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) was effectively finished as a fighting force and its heartlands and territories were now fully under the control of the Iraqi government. With the PUK defeated, the Ba’athist regime turned its attention north to Bahdinan, the principal stronghold of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP).

Morale was high amongst the Iraqis after the 8 August ceasefire that ended the Iran–Iraq War, and Ali Hassan al-Majid marshalled his army’s full resources to fight. Bahdinan offered a classic natural terrain for guerrilla warfare, with its landscape traversed by rivers, valleys, and mountains.

Anticipating a climactic battle, the Iraqis assembled as many as 200,000 troops to fight the KDP peshmerga, who numbered between 6,000 and 10,000. It was a complete mismatch.

Aside from ground troops, the Iraqi forces drew upon a chemical weapons battalions, units of the Iraqi air force and thousands of jash. Their strategy, as before, was to outflank Kurdish peshmerga and civilians, encircle and then overwhelm with massive force before destroying up to 400 Kurdish villages.

The enormous build up of Iraqi ground troops and planes was easy to see from the highways of the Duhok governorate as they attacked mountain communities along their way. Almost 70 villages were targeted with chemical weapons attacks during the Final Anfal.

The Eighth and Final Anfal began on 25 August 1988. The Iraqi air force attacked with multiple chemical bombings of KDP targets in the Bahdinan region, provoking mass terror amongst the Kurdish civilian population.

Final Anfal begins with multiple bombings in Bahdinan on 25 August 1988

In the spring of 1987, following Ali Hassan al-Majid’s appointment by Saddam Hussein, practically all of the Duhok region was ‘redlined’ by the Iraqis. This meant anyone who had not by 1988 surrendered to the government was considered a ‘saboteur’ or Iranian enemy fighter.

Consequently, Kurdish civilians and KDP peshmerga were long used to aerial bombardment in Bahdinan. Since the mid 1980s the Iraqis had regularly strafed the area following intelligence reports of peshmerga activity. So when planes approached, villagers instinctively fled to caves and other shelters.

Yet even though the news of the chaos caused by previous Anfal operations had spread to Bahdinan, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) leadership was unprepared for the sheer scale of the assaults their ground forces would face.

Before the Iraqis commenced their Final Anfal operation in earnest, they dropped poison gas on the KDP headquarters at Zewa Shkan, close to the Turkish border, on the evening of 24 August, killing 10 peshmerga.

The following day, the full fury of Anfal came to Bahdinan as the Iraqi air force bombed a string of targets simultaneously and with massive force. The result was mass terror.

Anticipating a climactic battle in Bahdinan, the Iraqis assembled as many as 200,000 troops to fight the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) peshmerga, who numbered between 6,000 and 10,000. It was a complete mismatch. Their strategy was to outflank Kurdish peshmerga and civilians, encircle and then overwhelm them with massive force.

Numerous Iraqi chemical attacks batter Kurdish villages in the Bahdinan region

Two of the KDP’s important regional bases in Tuka and Galnaske were hit with chemical bombs, as well as Birjinni, a village situated between them, and also the hamlet of Barkavr. Toxic gas clouds rose up to 50 feet in the air. Iraqi planes then hit the village of Tilakru, near the Khabur river, the peshmerga stronghold of Warmila village, Bilejan and Banye.

In Warmila, as in other villages, chickens, goats and other farm animals died very quickly. Villagers who survived the attack vomited and suffered horrific blisters on their skin, but a local peshmerga doctor injected them with atropine and several were able to flee north.

In other villages, peshmerga had warned locals to take precautions in case of a chemical attack. They closed the doors and windows of their homes and covered their heads in wet towels, before fleeing to evade the sweep of Iraqi forces through the following day.

The most concentrated chemical attacks took place on Gara mountain. Up to 50 villages were bombed by the Iraqis, including Avoke, Suwar, Sedara and Spindar. North of Gara mountain, the chemical assaults continued at the villages of Bawarka Sarkavri and Mergatui, as well as Sarke and Guze. Many other villages were also bombed.

Perhaps the most cowardly Iraqi attack was the chemical bombing of the bridge at Baluka, which many fleeing civilians used to cross the Great Zab river. Animal corpses were piled so high after the bombing that the bridge became impossible to cross, trapping civilians in areas that were now covered by toxic gas.

Guze village was preparing to celebrate a wedding when Iraqi jets attacked with poison gas. AISHA HAJI SALAM and her then fiancee ADAM MOHAMMED YOUNES were captured and two of their sons taken away by Iraqi soldiers.

‘Our time is coming to an end, but we’ll take this sorrow to the grave’

Aisha Haji and Adam Mohammed were preparing to celebrate a wedding in Guze when Iraqi jets began bombarding the village with poison gas.

The bride and groom escaped to Iran that same day, while Aisha and Adam fled Guze with their two sons and around 100 other families. The next day, jash forces surrounded the village and captured 99 men.

Those families who survived fled east to Iran or north to Turkey. Aisha, Adam and their family were less fortunate and were captured by the Iraqi army. They were eventually taken to Nizarka prison on the outskirt of Duhok city, where thousands of rural Kurds were collected, registered and imprisoned by the Iraqi army during the Final Anfal.

At Nizarka, Aisha’s two sons were tortured in front of her.

‘About 90 young men were lined up and their mothers and fathers were lined up to watch them’ she says. ‘The Iraqis hit them with a metal hose. They hit them over the head again and again until they bled profusely from the mouth and nose.’

After suffering this brutal treatment, the young men were driven away in army trucks and never seen again.

In August 1988 MOHAMMED ALI AHMED fled Warmila village in the Bahdinan region after it was attacked with chemical weapons. He describes how Iraqi planes flew overhead firing rockets, one of which landed close to him. Dizzy and sickened, Mohammed was rescued and taken to Betanirka village for medical help.

‘A poison gas rocket landed 10 metres from me’

A rocket containing poison gas landed close to Mohammed Ali Ahmed as he fled Warmila village towards the mountains nearby. It was 8 am on 27 August 1988.

A yellowish cloud of gas drifted towards him, and he immediately felt dizzy before falling face down on the ground, scarcely able to breathe. Semi-conscious, he heard voices nearby and realised they were talking of him as if he were dead. He lay there for eight hours or so. Some people then loaded Mohammed onto a mule and took him to Betanirka village. A doctor gave him an injection and he began to vomit.

‘At least I knew I was alive,’ says Mohammed.

Days later, Mohammed joined villagers travelling towards the Turkish border. Finding their way blocked by the Iraqi military, they surrendered and were put on army trucks. Mohammed felt as if his limbs were paralysed.

‘I felt like an unburied dead person,’ he says. They were taken to Nizarka fort where living conditions were squalid. For two nights Mohammed slipped in and out of consciousness.

‘I was lying on my back and couldn’t move at all, and if my mother hadn’t been with me I would have died,’ he says. ‘My leg, stomach and arm were rotting. It felt like there was a hole in my chest and there were no doctors.’

Whilst still at Nizarka, the surviving villagers from Warmila were amnestied and trucked to a facility in Baharka. Mohammed survived his injuries, even without shelter, food or water, but around 40 men and 30 children from his village lost their lives in the Final Anfal.

The massive scale and intensity of Iraqi attacks stunned the KDP leadership and it quickly became obvious they had no option but to retreat. MASOUD BARZANI instructed his peshmerga to help civilians flee to the Turkish border and they fought bravely to slow the Iraqi advance, saving the lives of thousands.

Masoud Barzani orders a retreat and over 65,000 Kurds successfully flee to Turkey

The Iraqi army’s colossal assault terrified peshmerga and civilians across Bahdinan. The sheer intensity of the attacks, which occurred on multiple flanks simultaneously, left peshmerga with little option but to abandon their posts and try to rescue their families by ensuring they had safe passage to Iran.

Facing impossible odds, Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) leader Masoud Barzani instructed his peshmerga that resistance was useless. ‘We cannot fight chemical weapons with our bare hands’, he told them.

The KDP fought a number of brave rearguard actions in an attempt to slow the advances of the Iraqi forces and give their people time to flee. But many of the locations where they tried to make a stand, such as Darava Shinyeh, were vulnerable to air attacks and the battles were short.

In most cases, Iraqi ground troops and jash swept into the bombed villages within 24 hours, although in some cases they waited a few days. By 28 August the Iraqi military’s occupation of the Bahdinan region was complete, and their bulldozers arrived soon afterwards to destroy any signs of human habitation.

Despite the best efforts of the Iraqi army to police the highway between the city of Zakho and Baluka, between 65,000 and 80,000 managed to navigate the route and flee to the Turkish border, although many were killed as they did so. They were either intercepted by Iraqi troops or bombed by fighter jets.

Nizarka was one of the most notorious prisons in the Bahdinan region. Captives suffered desperate conditions as food and water was scarce and medical help was virtually non-existent. During the Final Anfal Kurdish men and teenagers were typically taken to execution sites after first being detained at Nizarka.

Iraqis process male detainees in Bahdinan and then transport them to execution sites

For those Kurdish villagers captured by the Iraqi army following chemical attacks – such as the inhabitants of Guze, Mergatui and Warakhal, where many were captured – the events of the Final Anfal followed a familiar pattern.

Villagers were taken to temporary processing centres in Deraluk, Suirya Zheri, Kwane, Sarsink, Basawi, Hizawa, Mangesh fort and several public buildings in the town of Amadiya, which included a police station, school, army base and teacher union.