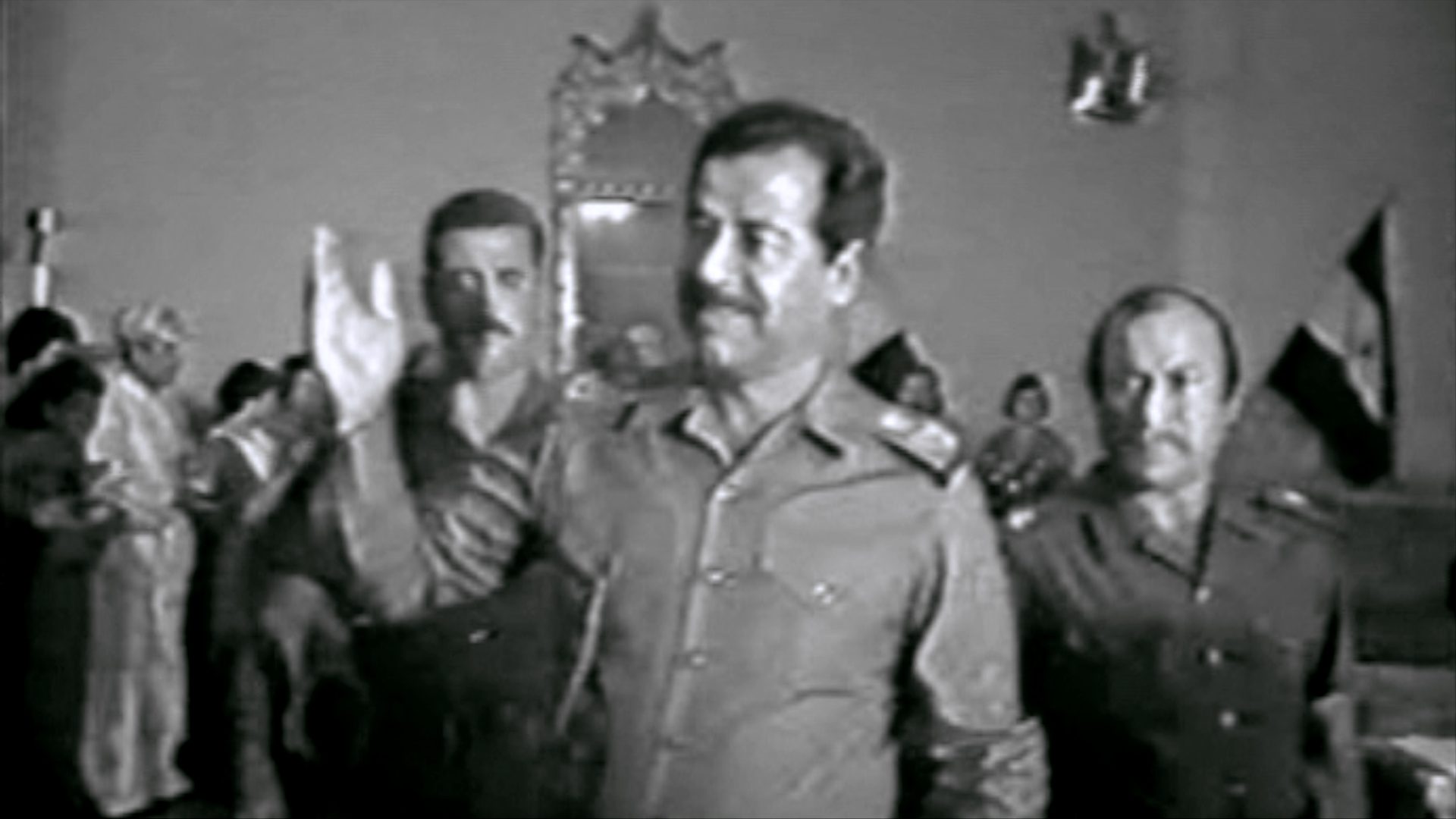

In late 1983, Saddam Hussein met Kurdish dignitaries in Erbil and suggested the missing 8,000 Barzanis, who had disappeared in July that year, had met a terrible end. The Barzanis were accused of having helped Iran in its war with Iraq.

On 31 July 1983, Doctor Bayan Rasul, a Kurdish psychiatrist, witnessed the mass abduction of Barzani males from resettlement camps in Kurdistan at first hand.

This mass kidnapping went unnoticed by the outside world but the emotional pain it caused is still deeply felt by the Barzani tribe – long regarded by Saddam’s regime as enemies of the state.

The men’s capture and subsequent execution became a blueprint for Saddam’s Anfal campaign five years later. Anfal led to the deaths of up to 182,000 Kurds.

It was tragic: after the kidnapping the camp was left without fathers, sons, neighbours and uncles

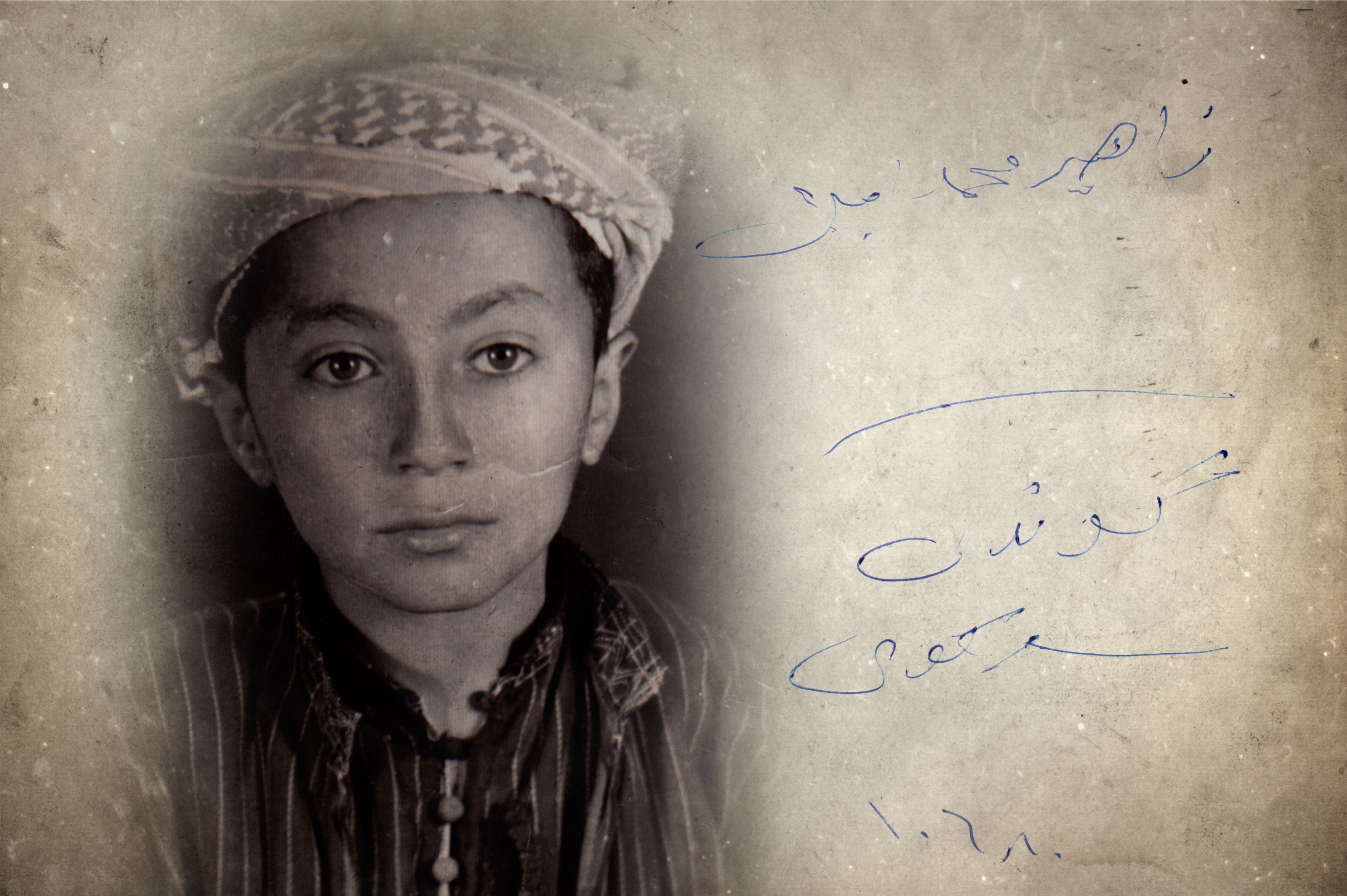

On that day in 1983 between 5,000 and 8,000 Barzani men and boys were taken from camps near Erbil and further north. Their families were told they would be working as labourers for a day before returning home. But they would not be seen alive again.

Despite strenuous efforts by clan leaders to find out what had happened to them, their fate remained a mystery until after Saddam Hussein was captured by the US army in the wake of the 2003 Iraq War.

Doctor Rasul saw some 50 buses refuelling at a petrol station near Erbil on 30 July and thought they were being used to transfer young Kurds to the battlefront for the war with Iran. The next day, as she tried to enter Qushtapa, she was stopped at a checkpoint and immediately suspected something more sinister was afoot.

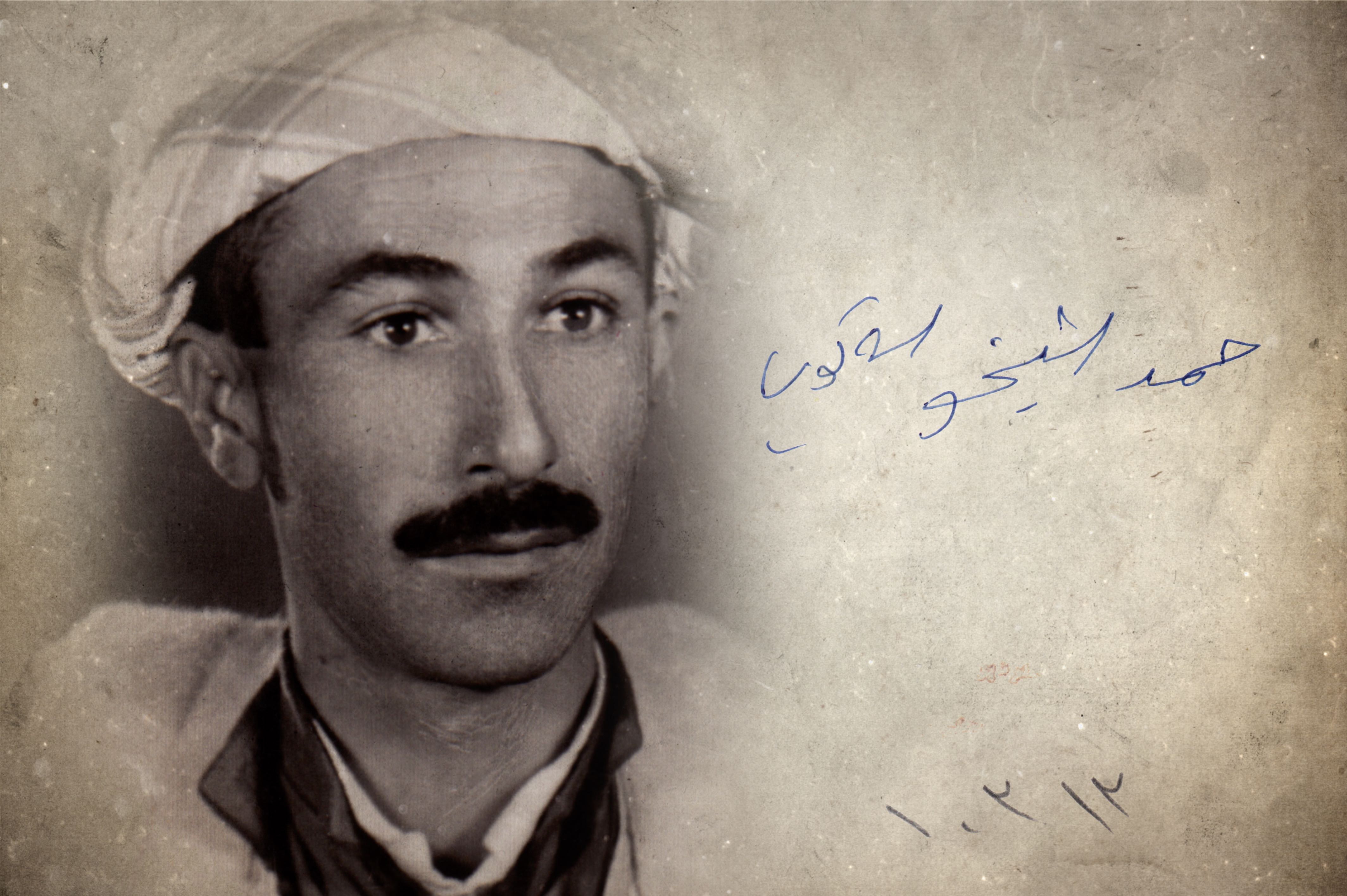

DOCTOR BAYAN GHADER RASUL GELALEE was an eyewitness to one of Saddam Hussein’s worst war crimes: the 1983 abduction of up to 8,000 Barzani males from camps in Kurdistan. She watched as 40 government buses carried the Barzanis off to an unknown destination. With no men to provide for or protect them, their wives and children were left destitute.

‘We saw that buses were entering the camp. They were big vehicles, each designed to carry about 40 passengers,’ she says. ‘When they drove out on to the Kirkuk road, I saw they had loaded up the entire Barzani male population at one of the camps. Their ages ranged between 10 and 80 years old.’

‘It was really tragic. The camp was left without fathers, without sons, without neighbours, and without uncles. Just women and children were left behind.’

‘My five sons and my husband are missing,’ said Habsa Hassan Fayzi, one of the Barzani women from Qushtapa whose family was taken. ‘My husband’s name is Malko, and my sons are Othman, Abdullah, Karim, Awni and Aziz.’

When those big buses drove out on the Kirkuk road, I saw they were transporting the entire male Barzani population from one of the camps. Their ages ranged between 10 and 80 years old

Being a barely qualified medic, Doctor Rasul had been put in charge of a medical centre at Qushtapa on the road to Kirkuk in 1982. There she looked after the medical needs of two nearby camps known as Al Quds and Al Qadisiyah which housed displaced Barzani families.

As an Iraqi Kurd her position there was unusual because these settlements were regarded as politically sensitive and kept under constant surveillance by the authorities. But the Iraq-Iran war was placing a heavy strain on Iraq’s medical services and qualified Arab doctors were in short supply. So the authorities had little choice but to let a Kurdish doctor run the Qushtapa clinic.

The Barzanis were badly treated at the camp and living conditions were harsh. There was a long history of enmity between the Barzani tribe and Baghdad which intermittently flared into open warfare over the years, and so distrust between both sides was deep.

This was made more acute by the failure of the March 1970 Agreement which granted the Kurds autonomy. The Kurds, led by the legendary General Mullah Mustafa Barzani, rose up against the Iraqi regime in 1974 with the backing of the Shah of Iran, but their rebellion collapsed a year later. While many Barzanis subsequently fled to Iran, many other families opted to stay in Kurdistan where they were forcibly displaced to the south of Iraq.

After Saddam came to power in 1979, however, these families were allowed to return to camps in Kurdistan. Most Barzanis opted to live in Qushtapa near Erbil but found they were being conscripted there to fight in the Iran-Iraq war. So many Barzani men tried to flee.

The situation at the Qushtapa camps in late July 1983 was tense. The war with Iran was not going well for the Iraqis and Saddam Hussein was furious at Masoud and Idris Barzani, who headed the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), accusing them of aligning their forces with the Iranians. Saddam’s regime decided to take its revenge on the captive Barzanis under its jurisdiction.

The Barzani women said their men might come back tomorrow, the next day or in two weeks. They waited constantly, their eyes fixed on the road

When Doctor Rasul arrived at the Qushtapa clinic on 30 July, she was shocked by the abduction of so many Barzani males from the Al Quds camp. Yet there were soon more clashes between Republican Guards and Kurds in the Qadisiyah settlement as more Barzanis were captured.

‘I heard a lot of gunshots,’ says Doctor Rasul. ‘The women had followed their men and been shot at. Two women and four children were wounded.’

She sent them to a hospital in Erbil for emergency treatment but was soon called in by the secret police for questioning. ‘I said it was my job as a doctor to treat them but they kept insulting me,’ she says.

The next morning, having returned from Erbil, Doctor Rasul asked the wives of her Barzani male employees to come and collect their wages. Once again, she faced questioning from the secret police for helping Barzani families after she was betrayed by a government informer working at the hospital.

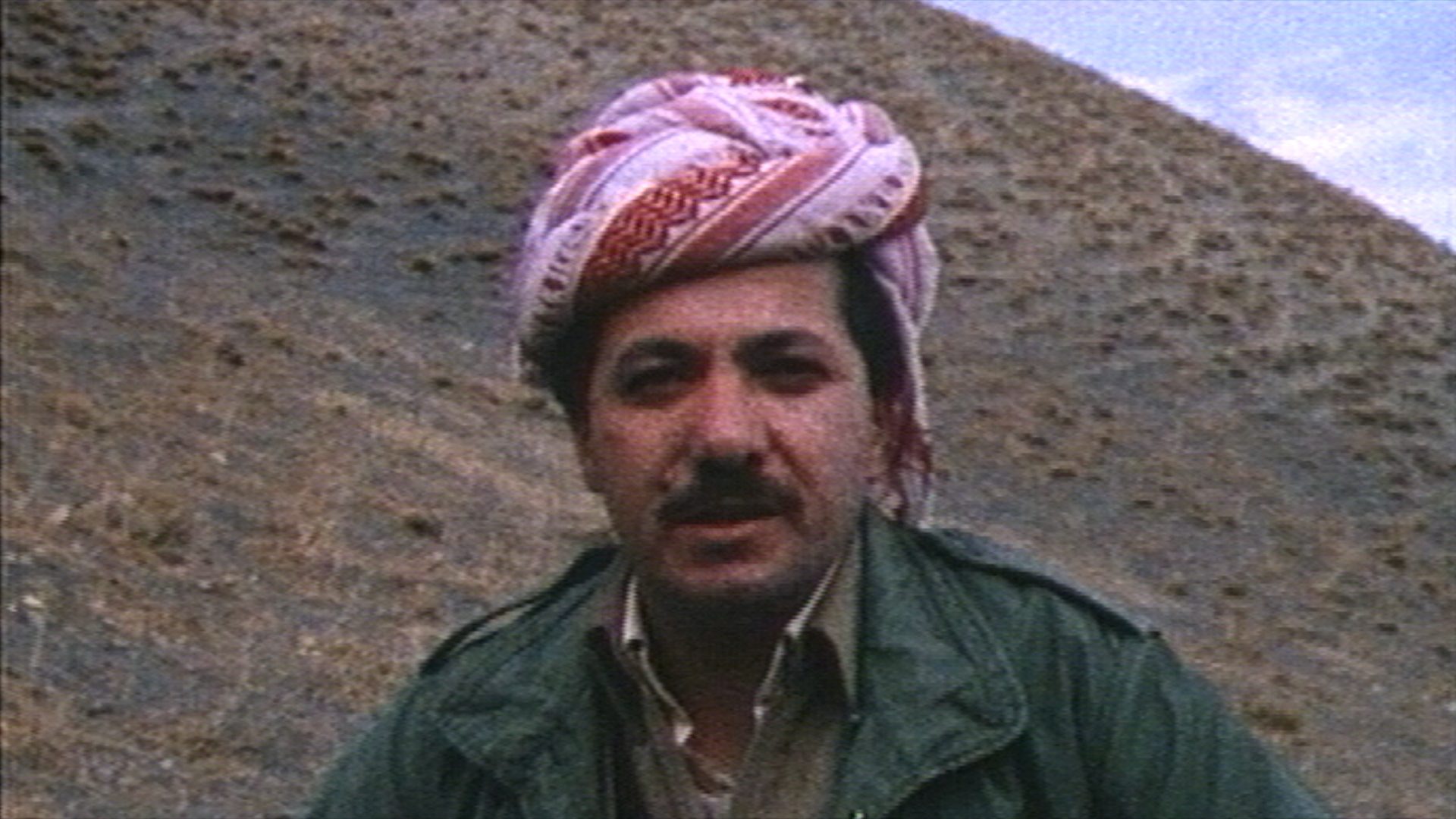

In 1985 a British journalist working for Independent Television News (ITN) reported the disappearance of 8,000 Barzanis from within northern Iraq. MASOUD BARZANI, their tribal leader, told him a large number had been executed and the rest taken to desert camps near Iraq’s borders with Saudi Arabia and Jordan.

The situation facing the Barzani women and children at the camps was desperate. They had given their gold and valuables to the Barzani men before they boarded the buses, and so were left without money nor men to support them.

The Barzani women never gave up hope their men might return. ‘They’d say they might come back tomorrow, the next day or in two weeks time. They were constantly waiting with their eyes fixed on the road,’ says Doctor Rasul.

A month after their disappearance at a public gathering of Kurdish dignitaries in Erbil, Saddam Hussein admitted publicly that his regime was involved in their disappearance, strongly hinting the Barzani men were no longer alive.

Kurdish leaders asked for information about the missing Barzanis, but Iraqi government officials consistently refused to give an answer

‘The Barzanis spread their treachery to other families.’ Saddam told his guests. ‘And they are involved in this crime and became guides for the Persian army and helped them occupy Iraqi land. Some who are called Barzani cooperated with them. So they’ve been severely punished and have gone to hell.’

In October 1983, Iraqi security forces backed by Republican Guards surrounded the Al Quds and Qadisiyah camps once again and detained more male Barzanis who had escaped arrest in August by hiding in cupboards and refrigerators. They were captured and were “disappeared” like the others.

During political negotiations with Iraqi government officials in the 1990s, Kurdish leaders asked for information on the fate and whereabouts of the missing Barzanis, but Iraqi government officials consistently refused to give an answer.

DOCTOR BAYAN GHADER RASUL GELALEE risked torture by helping Barzani women forced to live in Iraqi government camps in Qushtapa. She found them jobs with her relatives in Erbil, assisting between 20 and 25 families. As a psychiatrist she treated their depression, caused by the disappearance of their fathers, husbands and sons.

Throughout the intervening years, the Barzani women never gave up hoping their men were still alive. However, adapting to life without them was hard.

‘They were very traditionalist,’ says Doctor Rasul. ‘Before the men were taken, when the women came to consult me they never came alone. I’m a female doctor and they still couldn’t tell me about their illnesses: their men had to talk to me about their problems.

The Barzani women never thought they’d have to work to earn money. Yet suddenly they became the head of the family and breadwinners

I thought to myself, ‘“How can they survive without their men?” They didn’t know how to go to the market and buy things. They’d never shopped. They’d stayed at home letting the men do everything. They’d never thought they’d have to work to earn money. Suddenly they became the head of the family and the breadwinners.’

In the first year they started selling heaters, blankets, and knitted goods and then gradually found jobs working secretly for Kurdish families. But without their men, the Barzani women were vulnerable and lived in fear in the camps at night.

‘They were afraid of rape, of theft, or having their children kidnapped,’ says Doctor Rasul. ‘The older women suffered a lot because they kept guard during the night and next morning they had to work. It was painful to see and day by day, and year by year, the situation got worse.’

After Saddam’s defeat in the first Gulf War in 1991, the families of the missing 8,000 Barzanis were able to speak openly about their loss for the first time in eight years. They say they had no idea of what crime could have possibly warranted the abduction of their men.

Saddam’s regime threatened anyone who offered help to the Barzani women with arrest but Doctor Rasul was prepared to take the risk. She arranged for Barzani women to sit behind her on the bus to central Erbil.

When they reached their destination they got off and boarded another bus to the suburbs. ‘We never took a taxi because we didn’t want anyone to know they were with me.’

The Barzani women were introduced to families in Erbil who could help them.

‘If they were sick I would take them to a doctor,’ says Doctor Rasul. ‘I arranged for every three Barzani families to have one family in Erbil to look after them.’

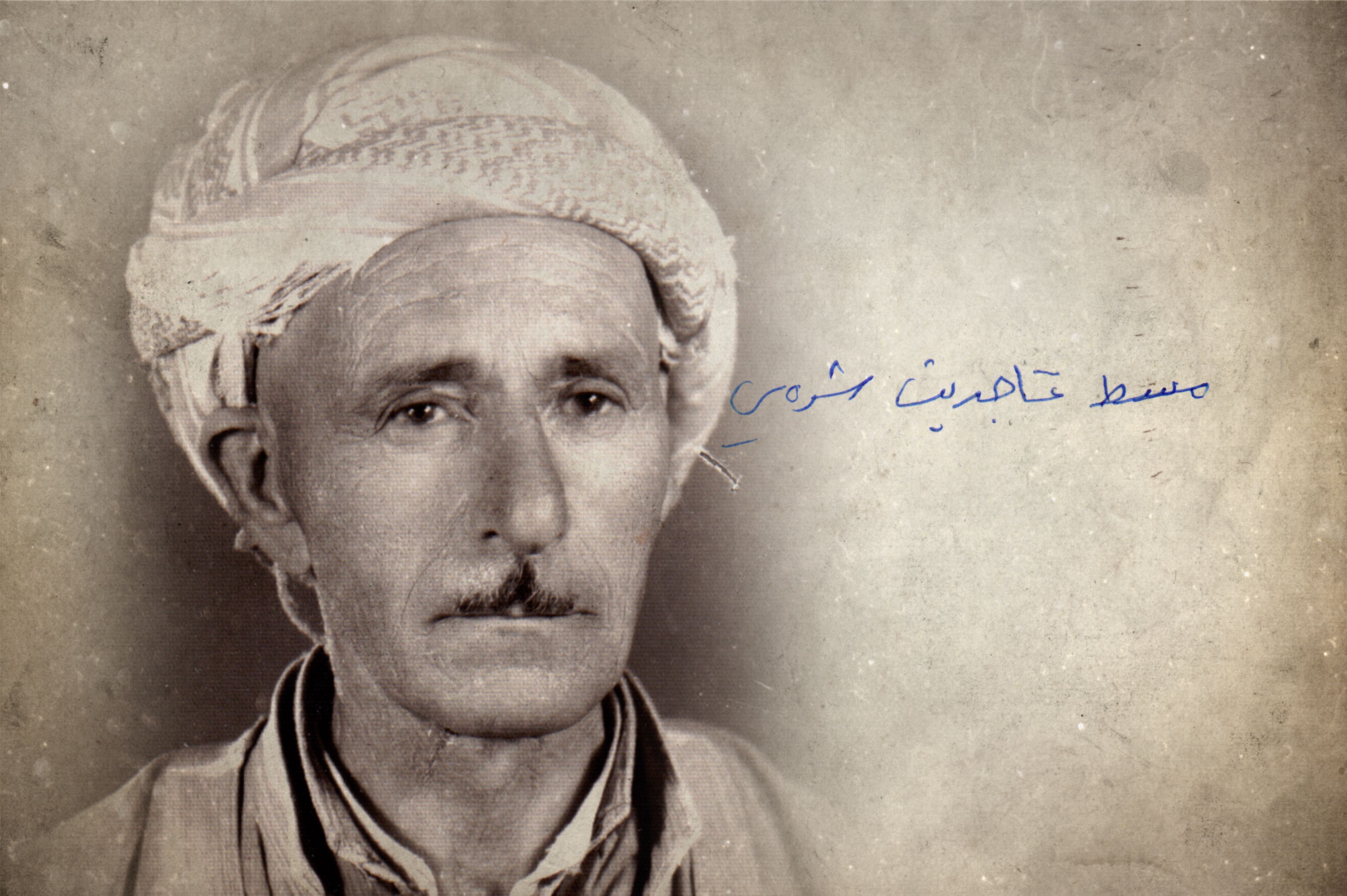

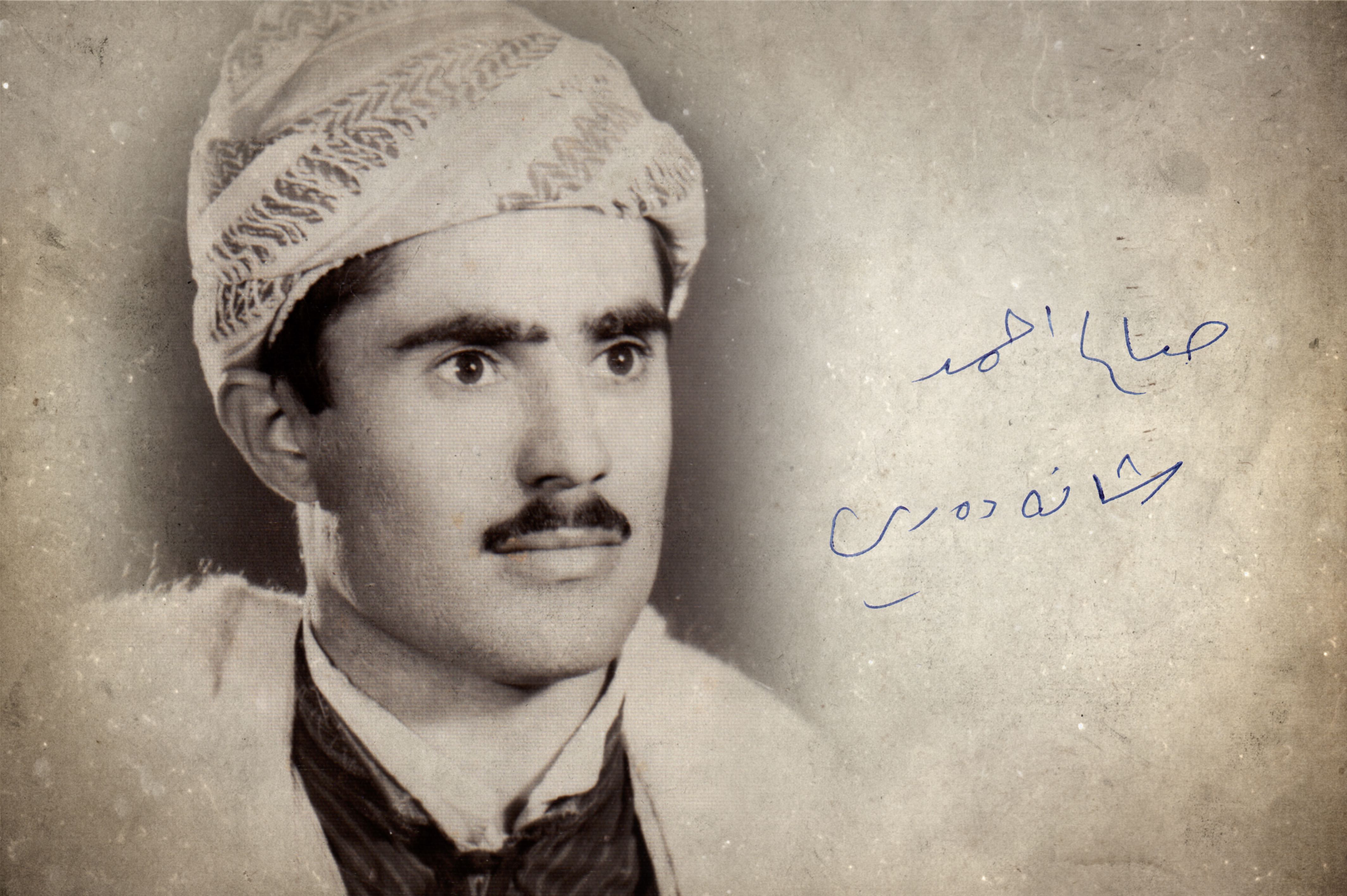

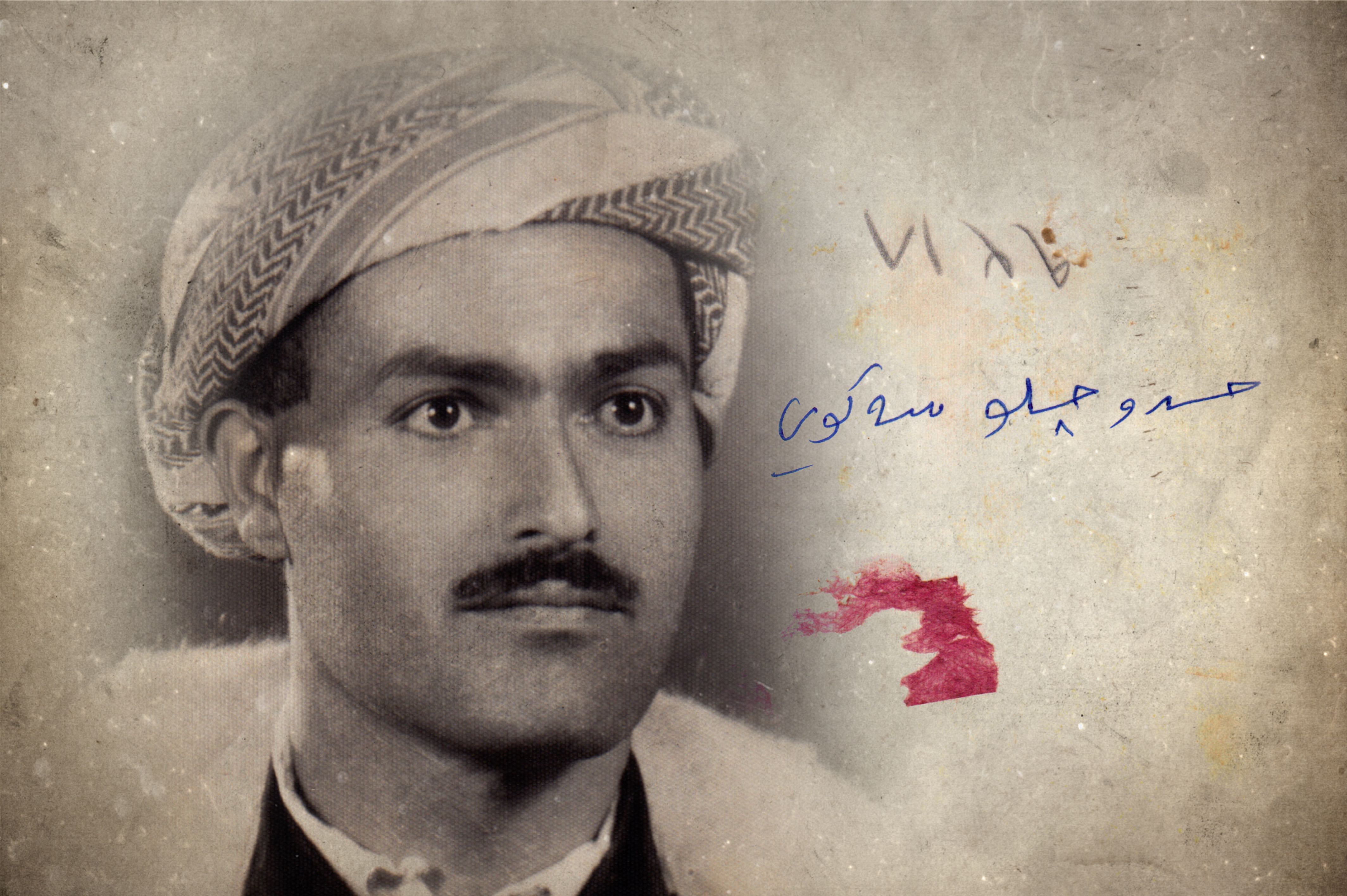

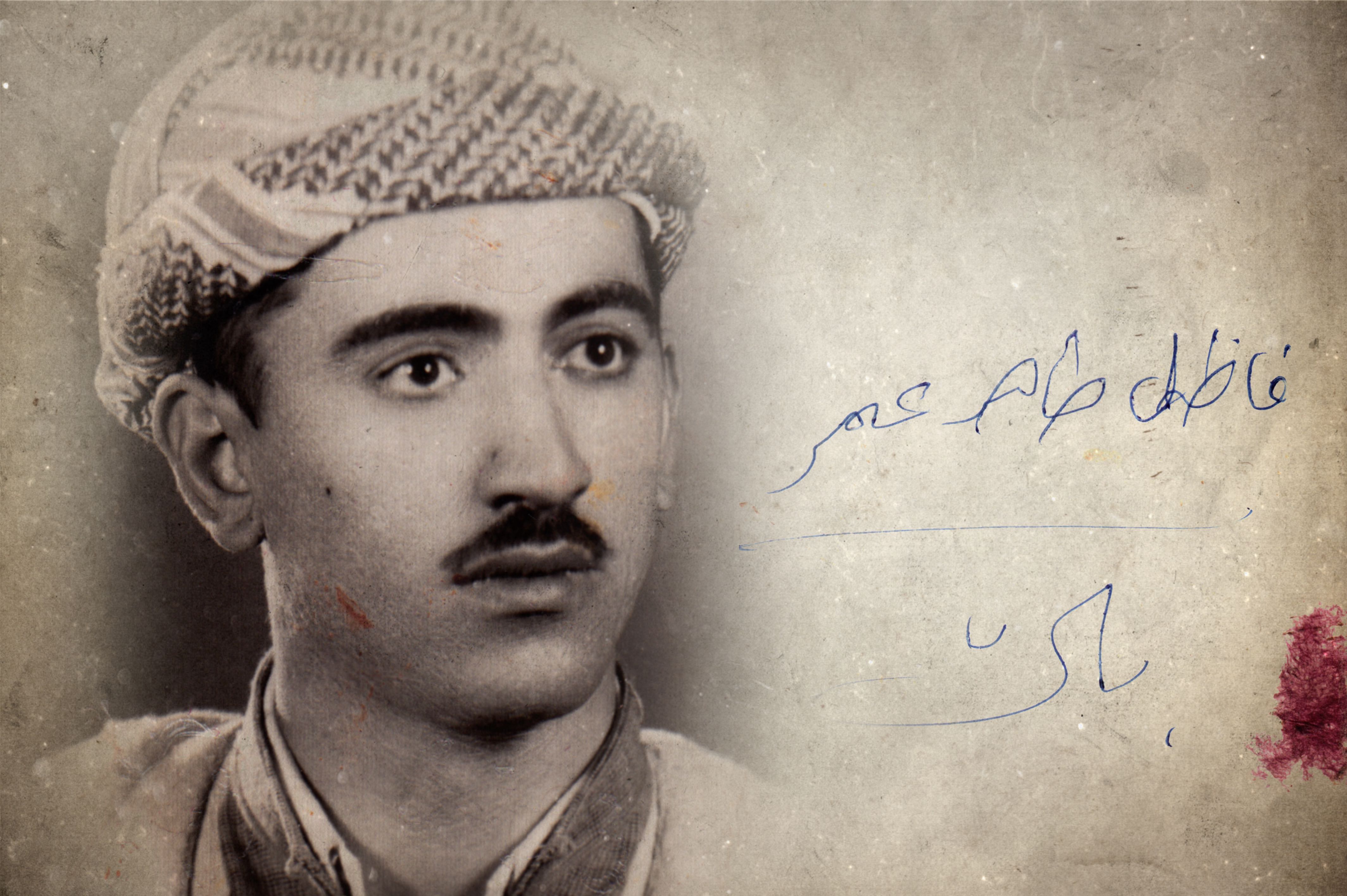

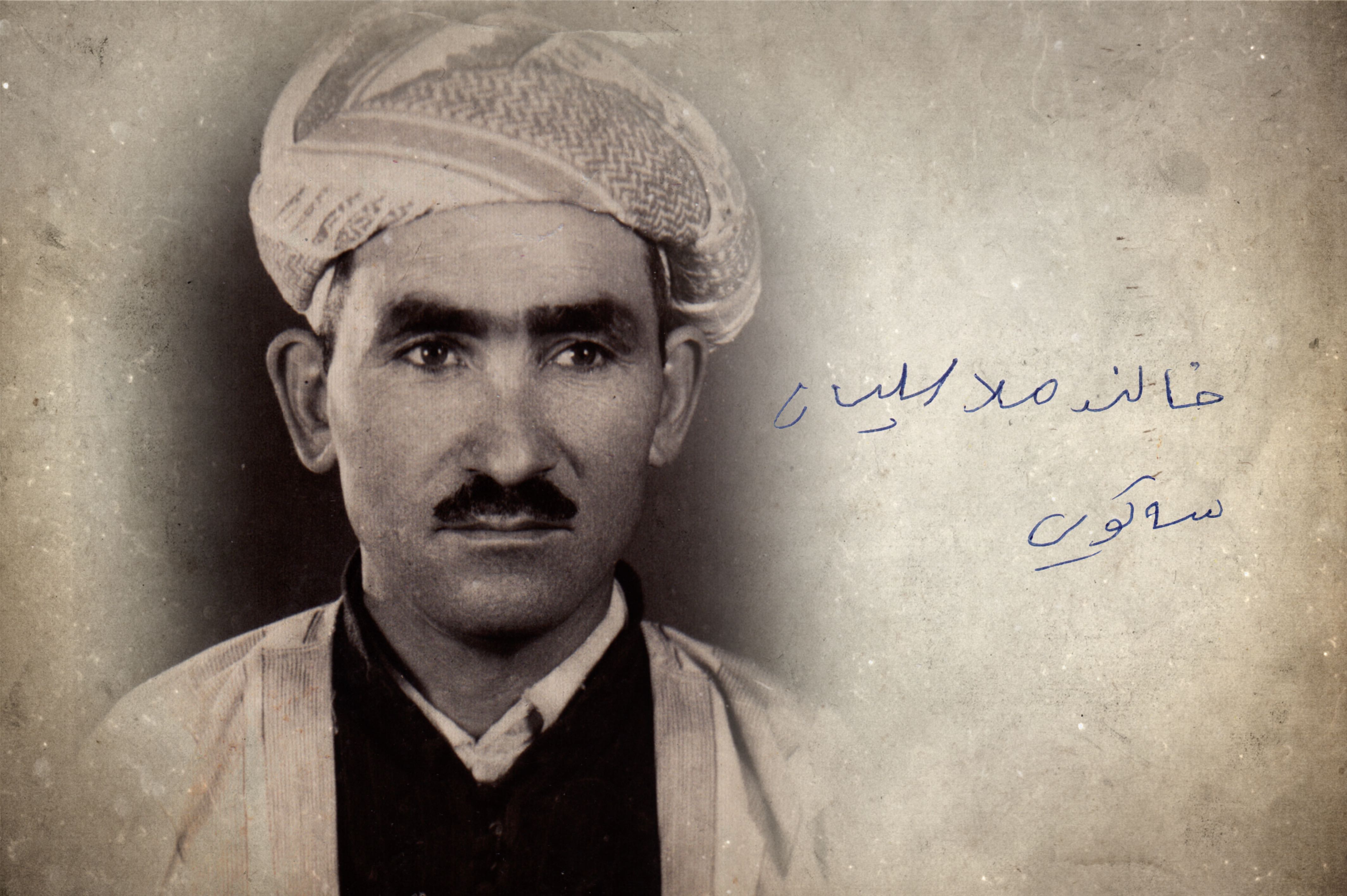

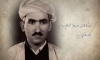

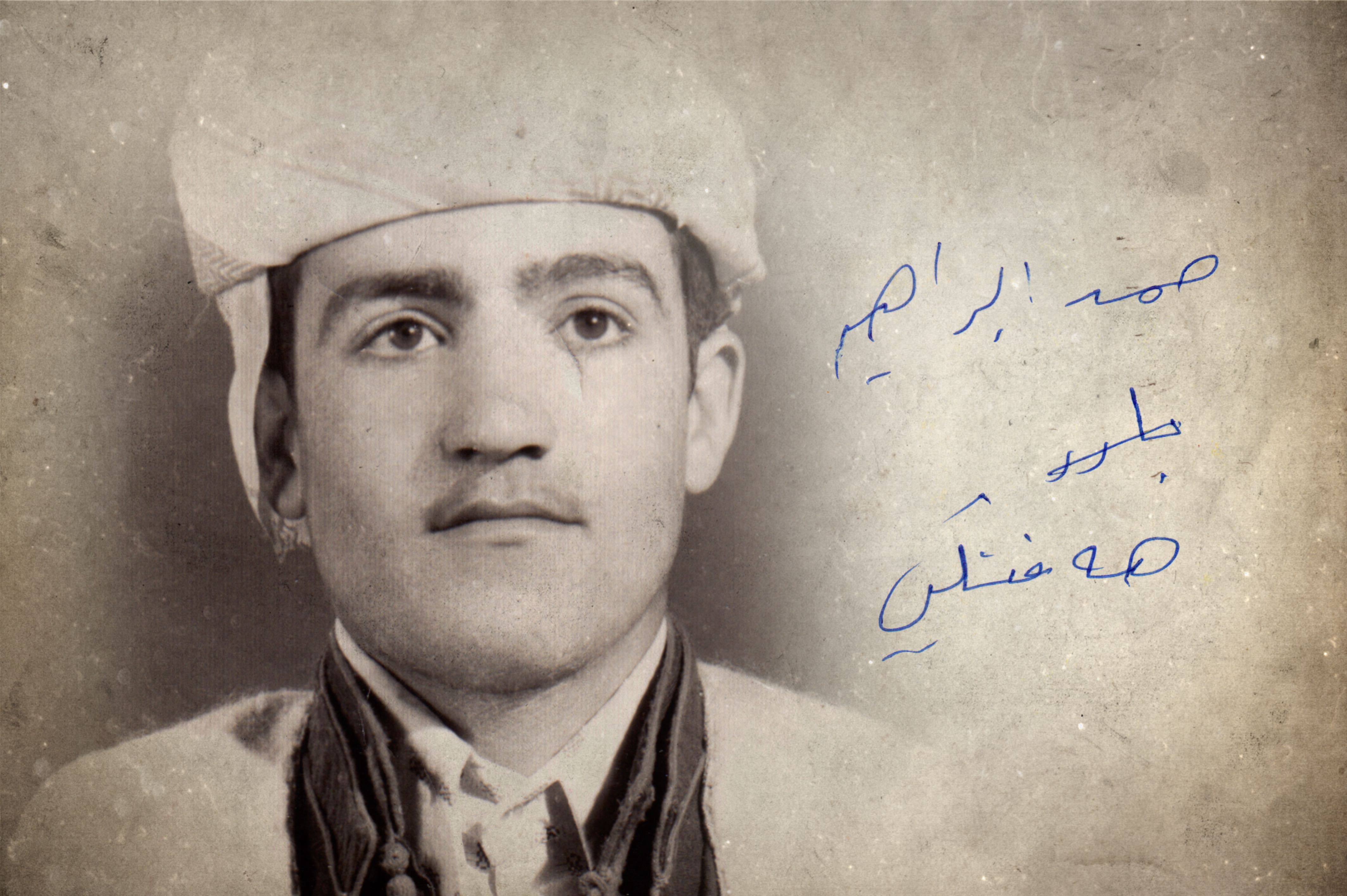

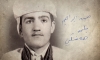

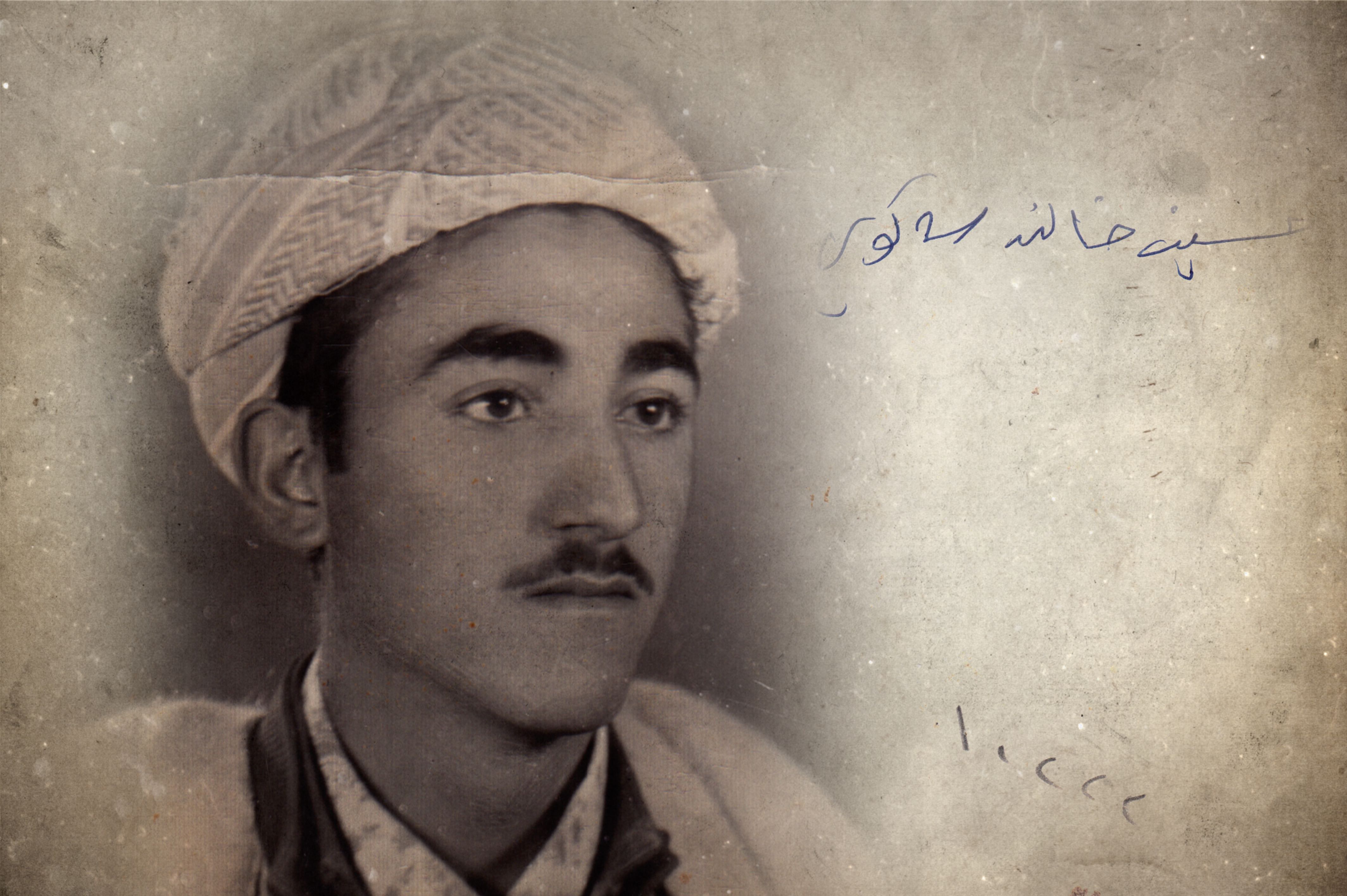

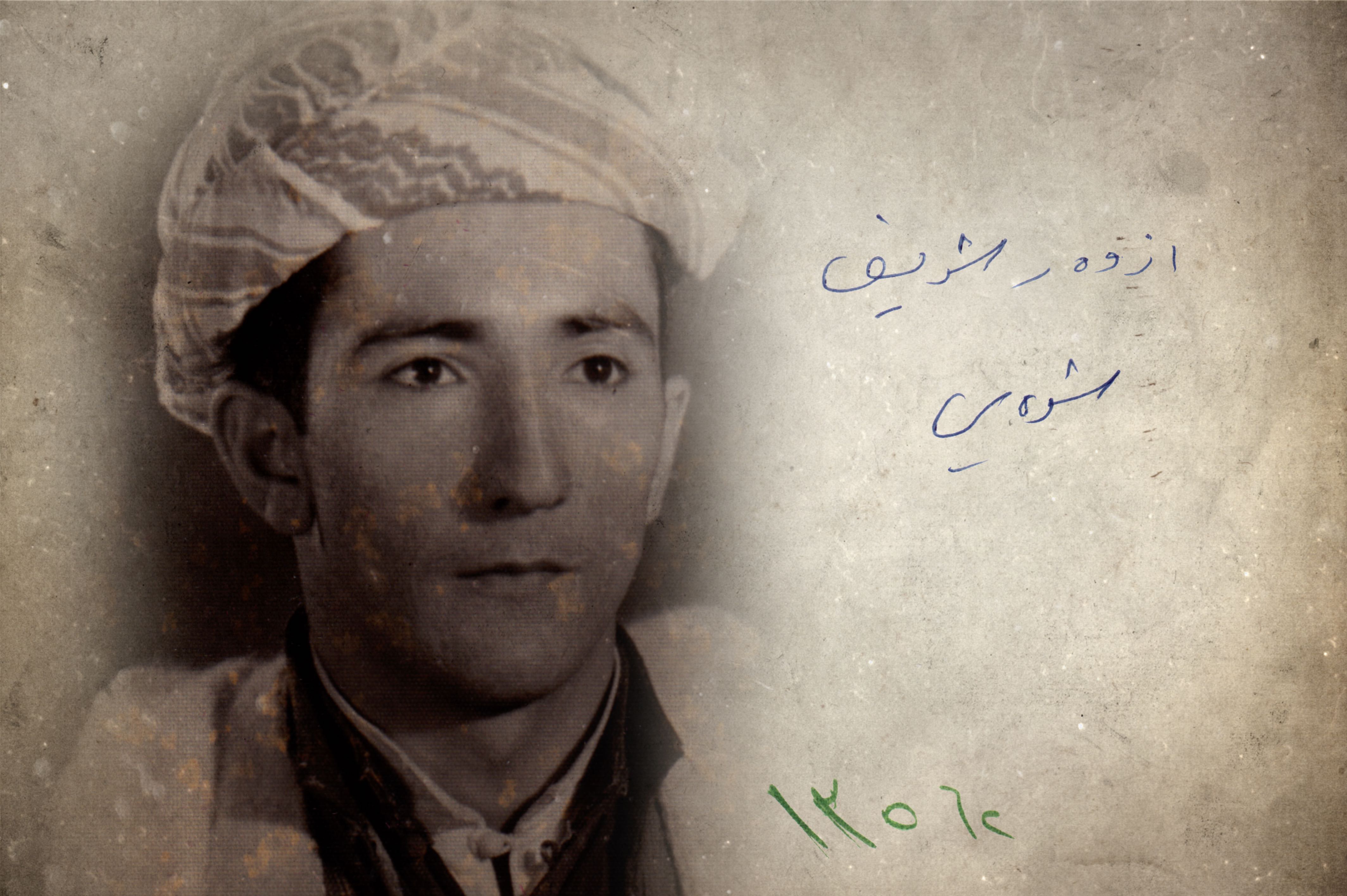

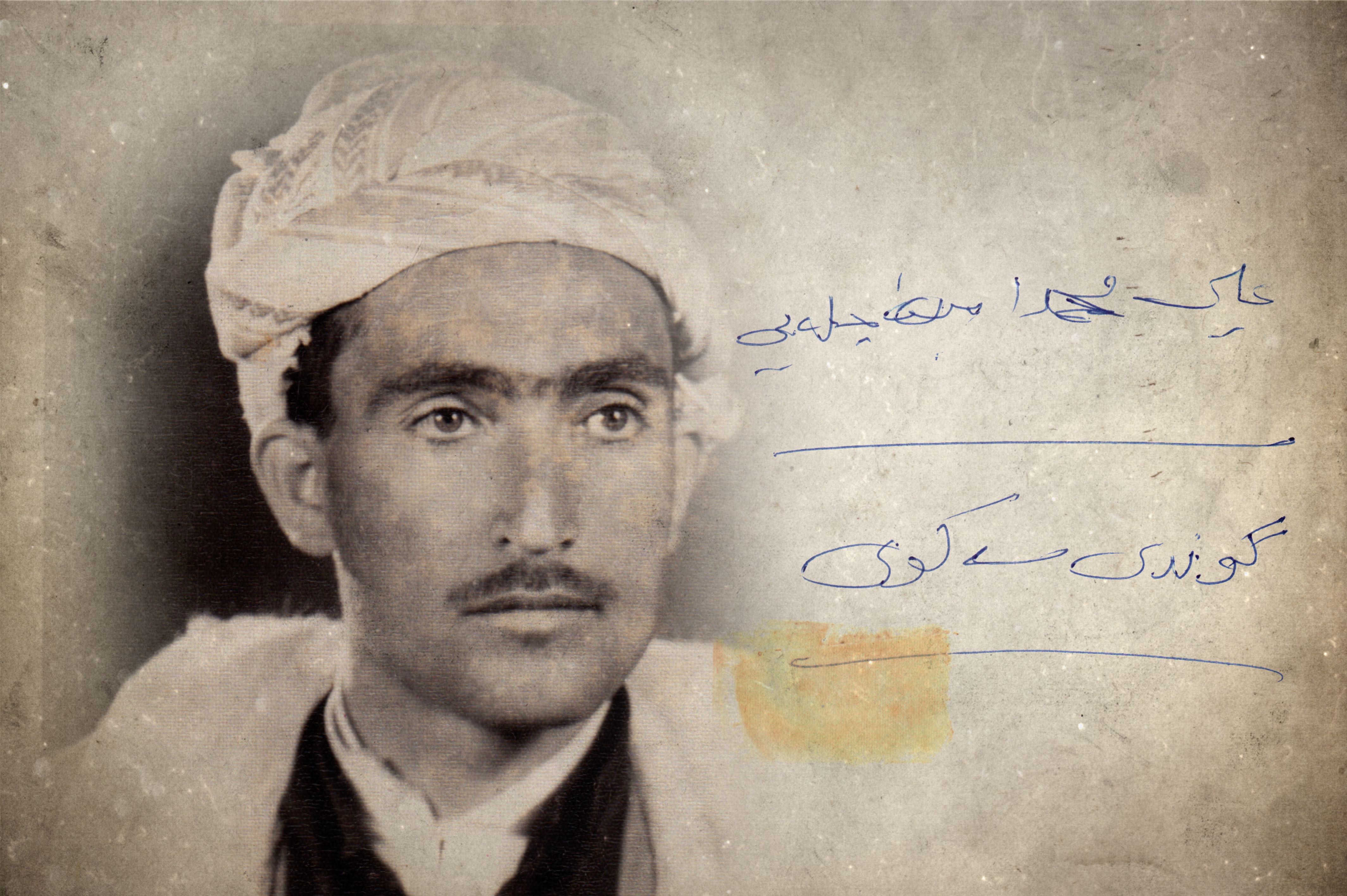

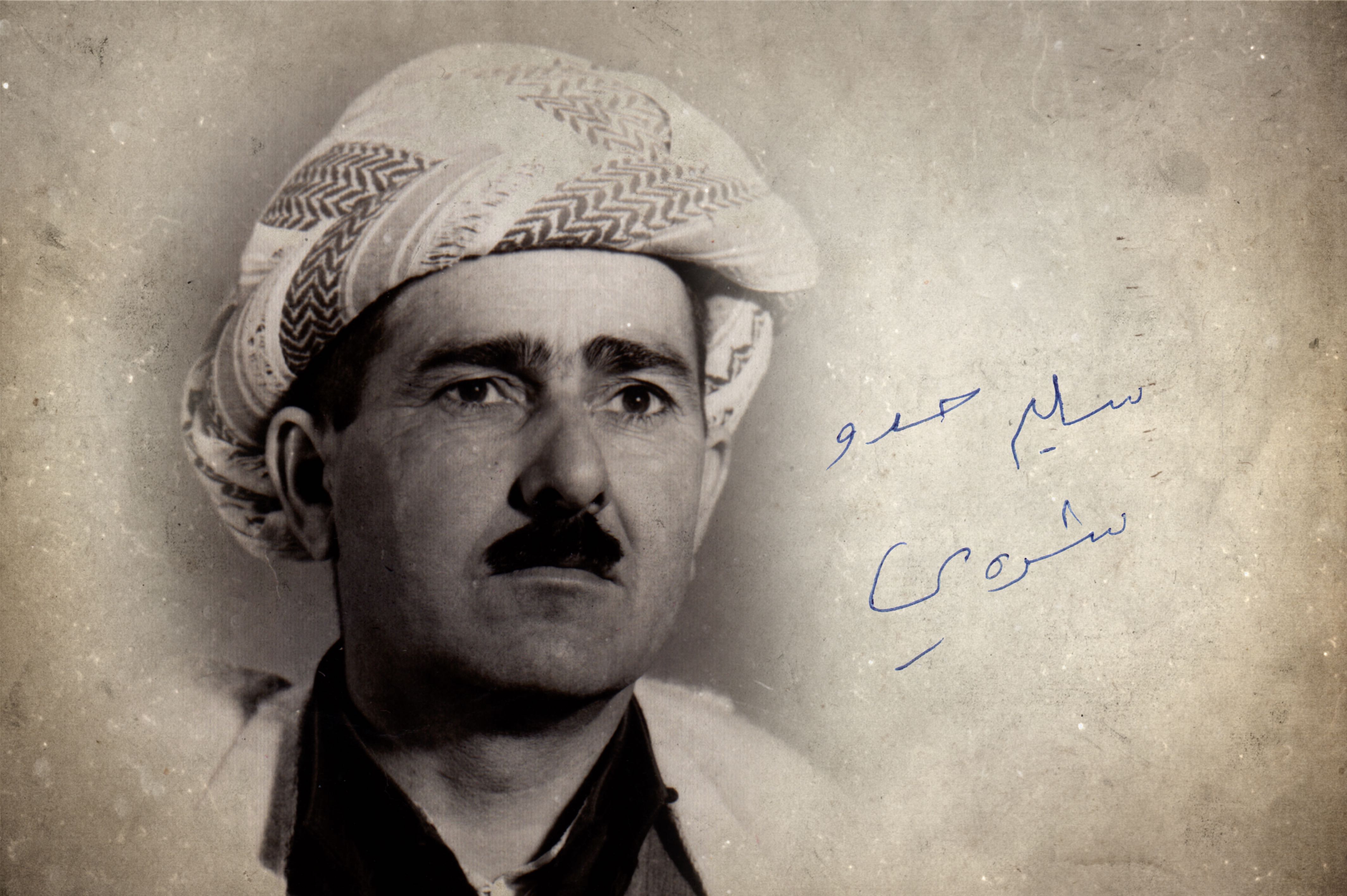

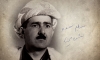

Still believing their fathers, husbands and sons may be still alive, the families of the missing Barzanis talk about their men in Harden village in the Barzan region, just south of Kurdistan’s border with Turkey. Speaking in 2005, they remember their lost ones as if they had last seen them yesterday.

The trauma the Barzani women had suffered left its mark though. None could understand why the Iraqis had treated them so cruelly.

‘My husband was a practicing Muslim,’ said Svetta Alexander Klashinko. ‘He didn’t drink, smoke or do anything bad. He was good with his family. He was educated and quiet. If someone is good, educated and handsome, isn’t that enough? What else could a woman want?’

‘The women were in pain because of stress and unable to relax. They would never laugh and were always crying,’ says Doctor Rasul. ‘Lack of sleep affected their muscles and caused spinal pain. They complained of heartburn, stomach and colon problems and headaches.’

Although illiterate, the Barzani women were brave. Their men would never have been able to cope with what they experienced

‘Many suffered from mental health issues, many were diabetic and had high cholesterol levels. During the day the older women met up holding pictures of their children. They wept together.’

‘They were emotionally in pain because of the traumatic events they’d experienced. But they still managed to bring up their children,’ says Doctor Rasul. ‘They were also secretly working and taking care of the older Barzani women. They were continually frightened because they were living under the regime in a very patriarchal society. They were always afraid of sexual harassment by men.’

Yet enduring such hardship made them tough. ‘The passage of time empowered the Barzani women,’ says Doctor Rasul. ‘Although illiterate, they were brave. Their men would never have been able to cope with what they experienced.’

As the years passed, rumours circulated that the Barzani men had been executed in the southern deserts. Masoud Barzani, the head of the clan, who had lost 37 members of his own family, authorised a search for the missing Barzanis. After the 2003 Iraq War this effort began to yield results.

Agents working for the Kurdistan Region’s intelligence services traced documents which reported that some 2,225 Barzani detainees had been taken to Nugra Salman, a desert prison 300km south of Baghdad. From there they had been moved to remote Bedouin encampments.

These documents also revealed that the Barzanis had been killed near Bussia, an Iraqi outpost near the Saudi border which had once been run by Saddam’s secret police.

After the 2003 Iraq War the Kurds launched a mission to find the 8,000 missing Barzanis in southern Iraq. It was headed by DOCTOR MOHAMMED IHSAN, who searched close to the Saudi and Kuwaiti borders.

In 2005, the Kurds launched an expedition to find the Barzani graves at the height of the insurgency. It was led by Mohammed Ihsan, the Kurdish Minister for Human Rights, who was accompanied by British filmmakers Gwynne Roberts and John Williams, and a small team of Kurdish bodyguards.

The group ran the gauntlet of the so-called Al Qaeda “corridor of death” south of Baghdad. But in Bussia they found important eyewitnesses who described how the Barzanis were bussed from Bedouin encampments to execution pits in the desert 40km away.

‘A bus would come carrying 45 people,’ said Abu Naif, a shepherd, who worked as a military bus driver in 1983. ‘It would come at dawn to Abu Jihad village. That’s where the Kurds were. They executed them all in one week.’

Three mass graves were discovered close to where the borders of Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait meet. The rest of the Barzani graves have yet to be discovered

Three mass burial graves were located close to where the borders of Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait meet. Bulldozers were used to uncover the remains of 500 Barzani males. Other graves have yet to be discovered.

The remains were brought back to Kurdistan in 2007 and only then did the Barzani families begin to accept that their menfolk were no more.

DOCTOR BAYAN RASUL reminisces with the Barzani women who she helped after their men were abducted in 1983. They describe themselves as “the living dead,” but say Doctor Bayan was like a mother to them.