AISHA TAHA ABDULLAH was at home when Iraqi forces gassed Sheikh Wasan in April 1987. She saw a cloud of dust rising over the village, and describes the panic which spread amongst her neighbours.

Doctor Zyrian Abdel Younes, a medic with the Kurdish peshmerga guerrilla fighters, heard aircraft flying over the mountain slopes over Balisan, a village tucked into the mountain slopes of a valley in Iraqi Kurdistan.

He watched from a vantage point, high above his small field hospital in an adjoining valley. Fourteen helicopters flew low from the southwest and six planes crossed the valley high above them before dropping their payload. The bombs detonated and a thick white smoke rolled down the valley towards the villages below.

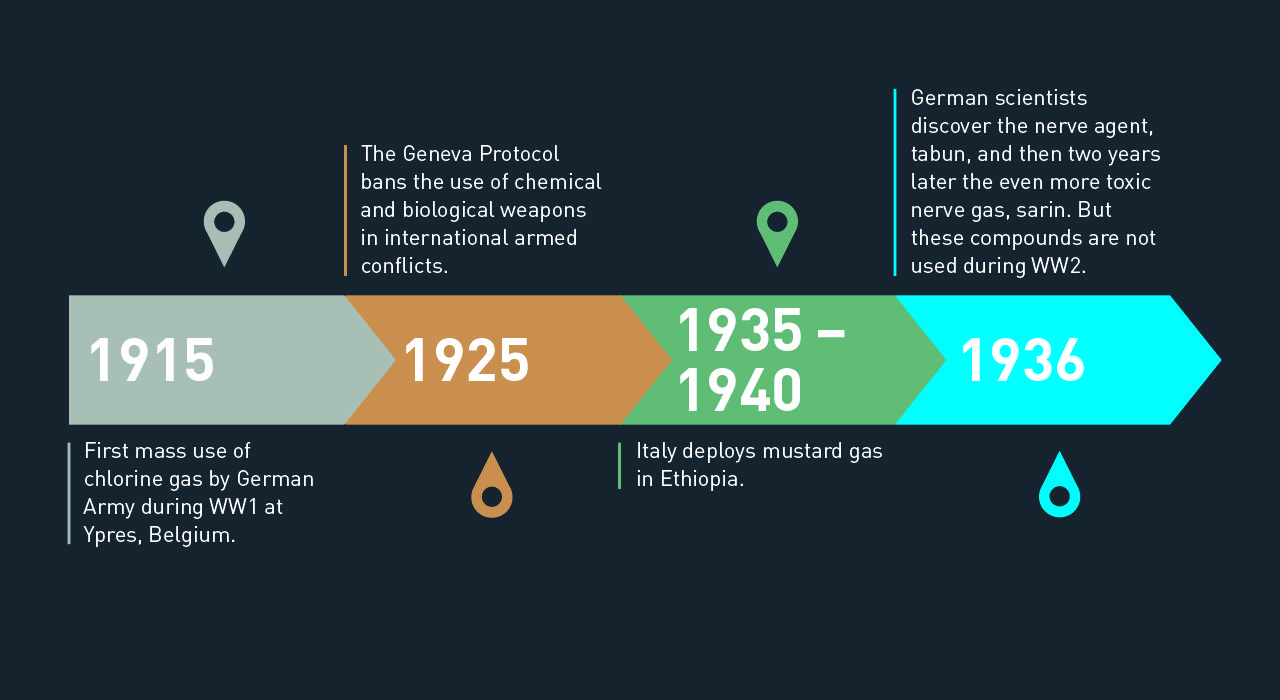

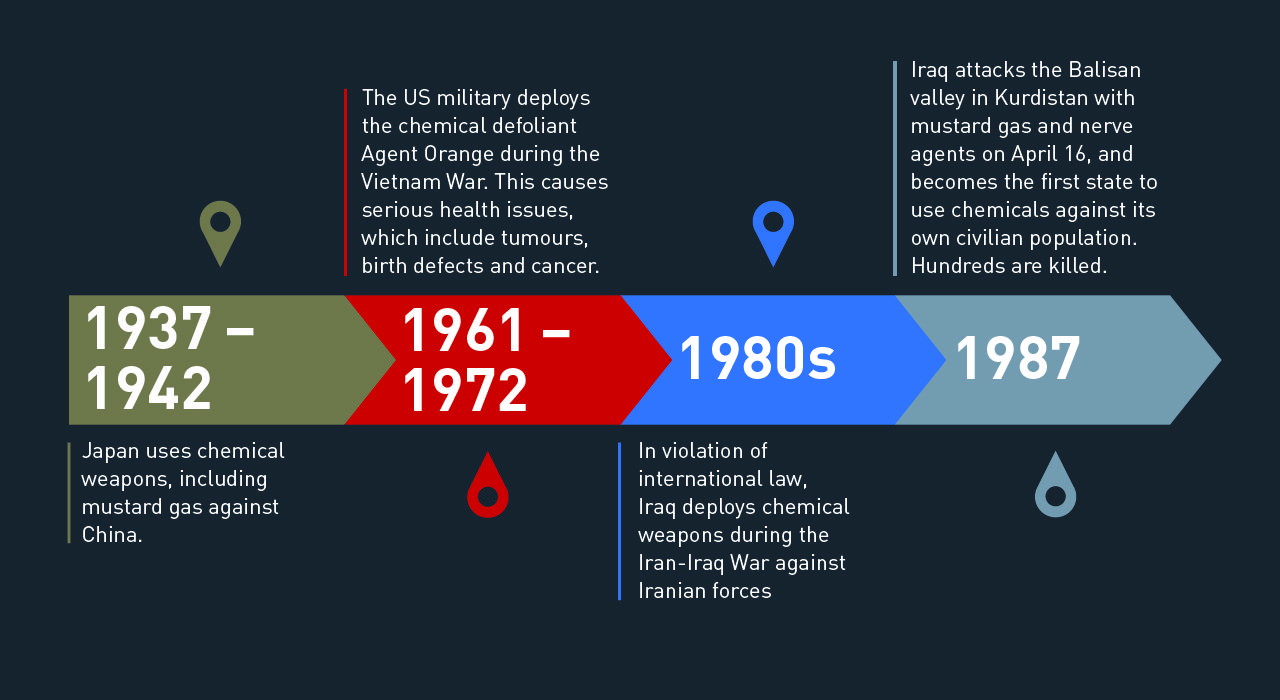

Ali Hassan Majid’s gassing of Balisan was the first time a government anywhere in the world had used chemical weapons on its civilian population

‘I knew instantly it was chemical gas,’ says Doctor Zyrian.

It was 16 April 1987. The Iraqi planes dropped chemical bombs in the light of the setting sun as villagers returned home from the fields for their evening meal.

DOCTOR ‘ZYRIAN’ ABDUL YOUNES, a Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) medical officer, assisted hundreds of injured who needed help after the chemical bombing of the Balisan valley in 1987. With a small group of paramedics, he evaded Iraqi Army “death squads”, who captured and executed any males who might have witnessed of the attacks.

Just weeks before, Ali Hassan Majid, Saddam Hussein’s cousin, had been appointed overlord of Iraqi Kurdistan and given exceptional powers to restore the government’s authority in Kurdistan.

By early 1987, much of the mountainous interior of Kurdistan was effectively controlled by peshmerga forces, with the Iraqi government’s command restricted to the cities, towns, and main highways.

I knew instantly it was chemical gas

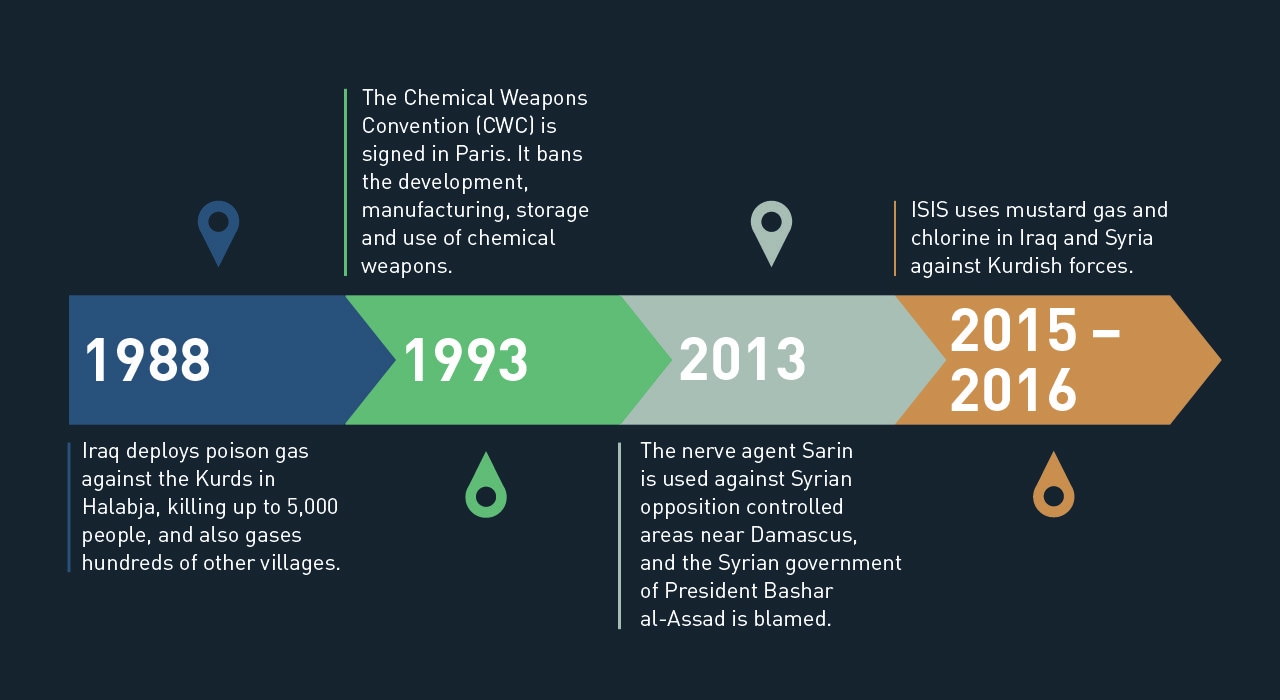

Ali Hassan Majid’s ambition was to crush the rebellious Kurds. The gassing of Balisan underlined that he would stop at nothing to achieve his objectives. The attack was the first time a government anywhere in the world had used chemical weapons on its civilian population. It occurred 11 months before the Iraqi gas attack on Halabja that killed 5,000 Kurds.

The people of Balisan and Sheikh Wasan had been caught by surprise when the chemical attack took place.

As bombs fell over their heads, many sought shelter in nearby mountain caves. After the first wave of planes left, Adiba Awlla Bayiz allowed her children to resume their games around their house in Sheikh Wasan. But she became alarmed when her daughter ran to her screaming.

I was frightened to the depths of my soul. People were dying everywhere

‘Mummy, Mummy, my tummy and my eyes are hurting,’ the girl cried before vomiting on Adiba.

‘Some of us were unable to stand on our feet anymore, some were retching and some screaming in pain, their skin burnt and their eyes watering,’ says Salam Hussein Aziz, also from Sheikh Wasan.

In this animation Iraqi jets drop chemical bombs on the villages of Sheikh Wasan in the Balisan valley, to the northeast of Erbil. The attack took place in the evening of 16 April 1987 as villagers returned home from the fields. The Iraqis bombed the village at supper time to maximise casualties.

The symptoms the villagers experienced were consistent with a range of gases, from nerve agents to mustard gas.

‘I was frightened to the depths of my soul,’ says Aisha Taha Mustafa, her neighbour. ‘People were dying everywhere.’

Najiba Khadir Ahmed was at home with her four children when the attack happened.

Refusing to believe the worst, some villagers returned to their homes. It was a mistake that cost many of them their lives

‘People collapsed,’ she says. ‘They’d gone blind and were vomiting. Our children defecated and vomited all night.’

Refusing to believe the worst, some villagers returned to their homes. It was a mistake that cost many of them their lives. During the night, children and adults began to retch and some lost their sight.

Aisha Taha tried to rise from her bed but was unable to stand. ‘I couldn’t lift my head off the ground, open my eyes nor look around,’ she says. Her son had difficulty breathing and had become partially blind.

Aware that the army would soon move into Balisan, many fled into the mountains. They knew they could expect no mercy. Their village’s support for the peshmerga meant that they had been classified as “Iranian agents” and this meant they faced imprisonment and possible execution if captured.

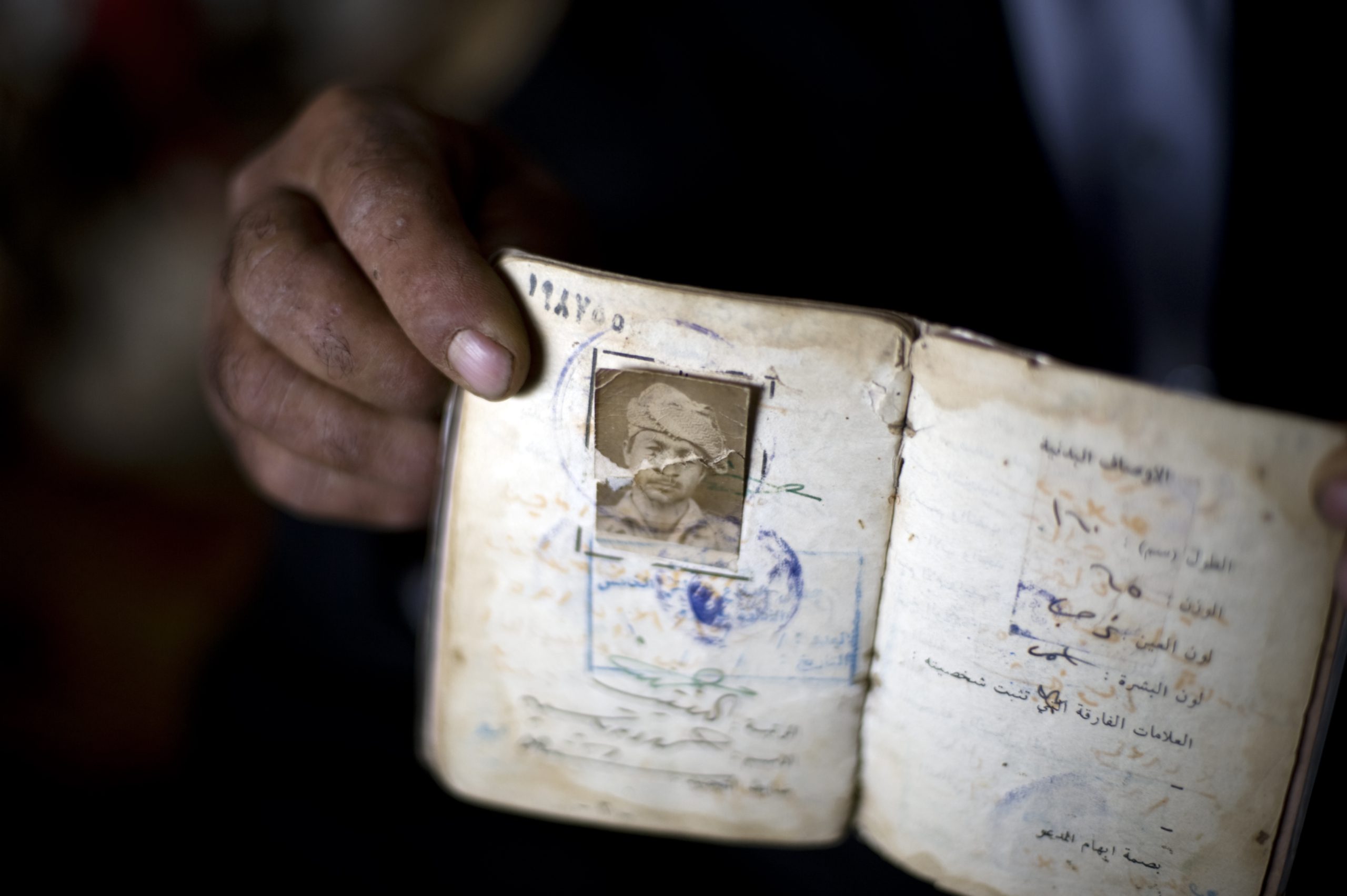

When Sheikh Wasan village was attacked by the Iraqi army, NAJIBA KHADIR AHMED escaped to the mountains with her children. Blinded by poison gas, she was led to safety by her sister-in-law. Her peshmerga husband, MUSTAFA RASUL HAMA AMIN, returned to find the village littered with the carcasses of dogs and cats

Doctor Zyrian’s clinic just outside Khate village was strangely quiet until 2 am the next morning. This brief tranquility was soon interrupted by the cries of children, the screams of women and the spluttering of tractor engines.

Hundreds of people flooded into his medical centre.

‘Most were blind,’ says Doctor Zyrian. ‘Lots of women brought to me by tractor had suffered miscarriages. Many were already dead, especially the elderly, and some people were covered in blisters from head to toe.’

As the sole peshmerga doctor in a region stretching from the Iranian border to Erbil, the Kurdish capital, his decision to abandon the clinic was not taken lightly.

On 16 April 1987, DOCTOR ‘ZYRIAN’ ABDUL YOUNES, a medical officer with the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), witnessed the chemical attack by planes on the Balisan valley. That night, hundreds of people who had been blinded by the chemicals and had massive blisters came to his medical station for help. Many of them died.

He and a small team of paramedics headed into the mountains and spent the night in a cave. Accompanied by a small group of villagers, they took with them eight patients who were strong enough to flee on foot.

‘It was a very, very difficult journey and we had to carry them at some stages between the rocks,’ says Doctor Zyrian.

In the aftermath of the bombing Sheikh Wasan was a living hell, with corpses lining the village streets

He did not venture to the villages attacked by the Iraqi planes for another two days. As dawn broke on 18 April, his group reached Sheikh Wasan. As they moved through the deserted village, Iraqi army tanks were visible in the distance heading towards them.

They threaded their way through the alleyways of Sheikh Wasan. It was deathly quiet and there was an awful odour. They would soon discover this was the smell of decomposing corpses.

‘It was a living hell,’ says Doctor Zyrian. ‘You saw bodies in the village streets; you saw women who’d died in childbirth; you saw all the animals were dead: birds, sheep, goats, horses… everything.’

They saw bodies lying on the floor inside the village houses. The group had travelled with little food and was tempted to collect what they could find inside. Yet Doctor Zyrian ordered them to leave it behind.

‘The food is contaminated and dangerous to eat,’ he told his companions.

They left after an hour and escaped into the mountains bordering Sheikh Wasan, where they hid for four days.

Although vomiting and unable to see,NAJIBA KHADIIR AHMED, escaped into the mountains on a donkey and sheltered in a cave. With her son hungry and in pain beside her, they stayed there until nightfall. Villagers then found them both and brought them to a hospital in Raniya. The next day, they were both imprisoned in Erbil.

When the army did arrive, its soldiers destroyed everything they could find.

Only two villages escaped intact – Sheikh Wasan and Balisan. However, this was only because both communities were so severely gassed the soldiers avoided them for fear the houses were still contaminated by chemical agents.

Many of the survivors from the Balisan valley attacks were rescued by Kurds from neighbouring villagers and driven by tractor to a hospital in Raniya, a town southeast of Balisan.

In one of their worst crimes, Saddam’s Ba’ath Party regime left around 300 Kurdish villagers, all of them badly burned with poison gas, to die in Erbil’s security prison

They stayed there overnight and were then bussed by Iraqi security officials to a hospital in Erbil. Refused treatment, they were moved to a local prison.

What happened then constitutes one of the ruling Ba’ath Party’s worst war crimes: they left 300 Kurdish villagers, who they had badly burned with poison gas, to die in Erbil’s security prison.

Mohammed Rasul Qadir, a former teacher, who had been imprisoned because his two brothers were known peshmerga, was an independent witness to the events.

MOHAMMED RASUL QADIR was a prisoner at Erbil Security Prison when the victims of the Balisan valley chemical attacks arrived. Locked in a cell, he peered through an air vent and saw children crying for their parents and villagers screaming in pain and unable to walk.

‘We cried because what we saw was difficult to bear,’ he says. Prison guards allowed him to leave his cell. As he walked through the prison, he saw four children lying on the floor scarcely able to breathe. Two others were dead.

He saw children crying out for their dead mothers and fathers. Some of the children were blind and unable to speak because the gas had burned their throats.

‘All of the children were laid out on the ground and some were dead,’ he says. ‘No breathing, no movement. I have never seen anything like that in my life.’

When you heard their songs of lament in that prison, you felt so sad. A father sang for his son, a mother for her daughter and a son for his mother

The memory of a pregnant woman who died in Erbil prison still haunts him. ‘We didn’t know what to do,’ he says. ‘We didn’t have a knife to cut open the woman’s stomach to save the baby. After some time the baby became silent and died.’

Mohammed remains affected by the songs he heard in that prison as families lamented their dead. ‘When you heard their voices, you felt so sad. A father sang for his son, a mother sang for her daughter, a son sang for his mother.’

He says 57 people from Balisan died in the Erbil security prison. He knows the exact figure because he carried every single one of the dead into the yard outside where the corpses were disposed of.

After seven or eight days, all the remaining male prisoners from Balisan were loaded into a coach by guards and driven away. They were never seen again.

The remaining women and children were released two days later and transported to Khalifan, a small town that is a two-hour drive northeast of Erbil. Nine died from their injuries on their first day of freedom after their release from prison.

DOCTOR ‘ZYRIAN’ ABDUL YOUNES witnessed the chemical bombardment of the Balisan valley in April 1987 when he was a medical officer for the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). He reflects on how the West ignored these attacks, and thus allowed Saddam to continue with his genocidal Anfal campaign against the Kurds.

Doctor Zyrian revisited Sheikh Wasan a week after his initial flight into the mountains and found that all the corpses had been removed from the village. He then returned to Khate to reopen his clinic.

He estimates that in total 203 people died in the gas attacks on Sheikh Wasan and Balisan villages in April 1987. Both communities were gassed again the following year during Anfal.

The effects of the gassing are still being felt in the Balisan valley some 30 years after the attack. Many survivors still suffer from respiratory and skin problems and their eyes are sensitive to light. Many remain deeply affected by the psychological trauma of seeing their families and neighbours perish around them.

The effects of the Iraqi army’s chemical attack in 1987 are still being felt in the Balisan valley some 30 years afterwards

DOCTOR SAREN AZER is a Kurdish medical specialist who practiced in Canada and regularly visits Iraqi Kurdistan to treat Anfal victims who survived poison gas attacks in the late 1980s.