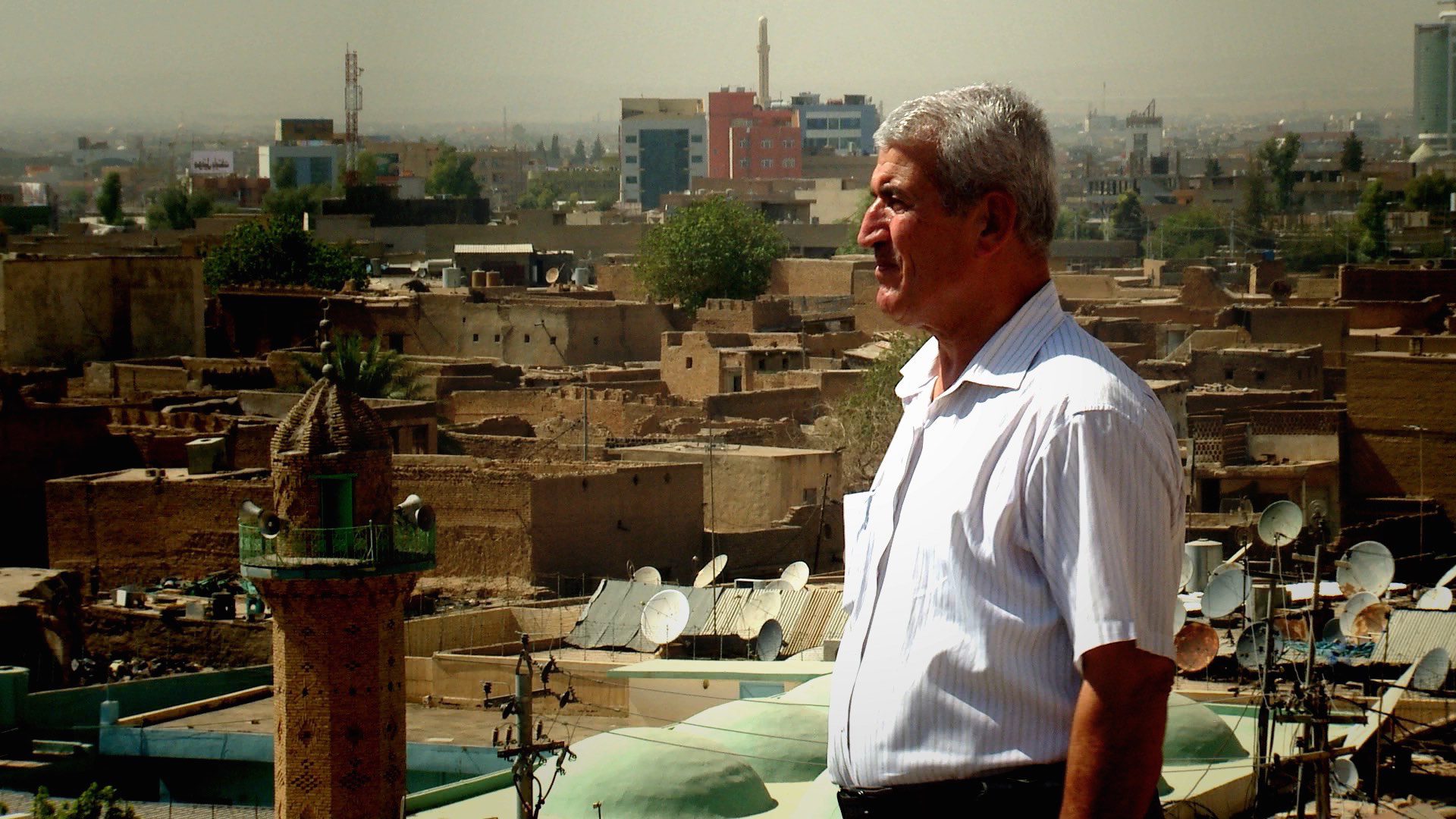

Mohammed Rasul Qadir, a former teacher, was an independent witness to one of the Ba’ath regime’s worst war crimes: the imprisonment of some 300 Kurdish villagers who were badly burned in a chemical attack in 1987 and left to die.

Jailed himself because his two brothers were known peshmerga, Mohammed Rasul climbed on to the shoulders of a fellow prisoners so he could see above the door of his prison cell.

‘I couldn’t say anything for about four or five minutes,’ says Mohammed. ‘There were old people and young people, men, women and children. They walked hand in hand. They fell over and screamed. Their eyes and mouths were in pain and it seemed their legs and arms had been burned.’

‘Who are you? Where are you from? What happened to you?’ shouted Mohammed.

‘Chemicals, chemicals, we were attacked with chemical bombs,’ one of them replied.

I have never seen anything like that in my life

The new prisoners were from three villages in the Balisan valley, 90 minutes drive northeast of Erbil: Sheikh Wasan, Balisan and Kani Bard. These communities were attacked by Iraqi jets two days previously, on 16 April 1987, because they supported the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) peshmerga against the central government.

‘We cried because what we saw was difficult to bear,’ says Mohammed. Next morning he was allowed out of his cell and saw four children lying on the ground nearby. One of them had red hair and was breathing strangely. Two others were dead.

In one of the bigger halls the scene was equally tragic. ‘All of them were laid out on the ground and some were dead,’ says Mohammed Rasul. ‘No breathing, no movement. I have never seen anything like that in my life.’ Children cried out for their dead mothers and fathers; some children were blind and unable to speak because the gas had burned their throats.

One blinded man held his dead child called Taha and refused to believe the boy had died. ‘I will never forget that old man until the end of the world,’ says Mohammed Rasul. Another child whose parents had just died was put in Taha’s place. After initially disbelieving Mohammed, the blind man finally accepted him as his son.”This is Taha,” he said finally.”Thank you.”

They took us to the execution site twice and gave us our last rites

I thought they'd been attacked with fists, rifle butts and bats – I never thought they'd been gassed

We tied babies to their blinded mothers with material from their dresses

The prison guards didn't give them a thing to eat, not even a grain of rice

I saw mothers sing laments for their daughters, sons for their mothers and men for their dead wives

What did small children do to deserve being attacked with chemicals?

Amidst the extreme cruelty of the guards, there was also kindness, particularly from Shia prison officers who bought medication with their own money for the prisoners. Mohammed also went out of his way to help others. He cleaned up blind prisoners who were unable to look after themselves.

He remembers the laments he heard in prison as villagers commemorated the death of close relatives. ‘When you heard their voices you felt so sad. A father sang for his son; a mother sang for her daughter; a son sang for his mother.’

Mohammed is still traumatised by the memory of a pregnant woman who died in the prison. He and other prisoners tried to save the life of the unborn baby.

An old man who had been blinded held his dead child, Taha, in his arms. He refused to believe the boy had passed away

‘We didn’t know what to do,’ says Mohammed. ‘We didn’t have anything like a knife to cut open the woman’s stomach to help the baby. After some time the baby became still and died.’

Mohammed Rasul estimates 57 people from the Balisan valley died in the prison and he carried all of them out to the yard outside where the corpses were disposed of.

After seven or eight days in prison, all the men from Balisan were loaded into coaches, driven away and never seen again. The women were released two days later and transported to Khalifan, a small town two hours drive northeast of Erbil. There, they were abandoned at the side of the road before being rescued by the townspeople of Khalifan and returned to their surviving relatives.

Mohammed himself was released four months later and joined the peshmerga.