Ten years after the crippling 1988 attack on Halabja by the Iraqi army, a British television team returns to the city to investigate the long-term effect of chemical weapons on its inhabitants. They find a tragedy that has not only escaped the notice of the outside world but also the Kurds themselves.

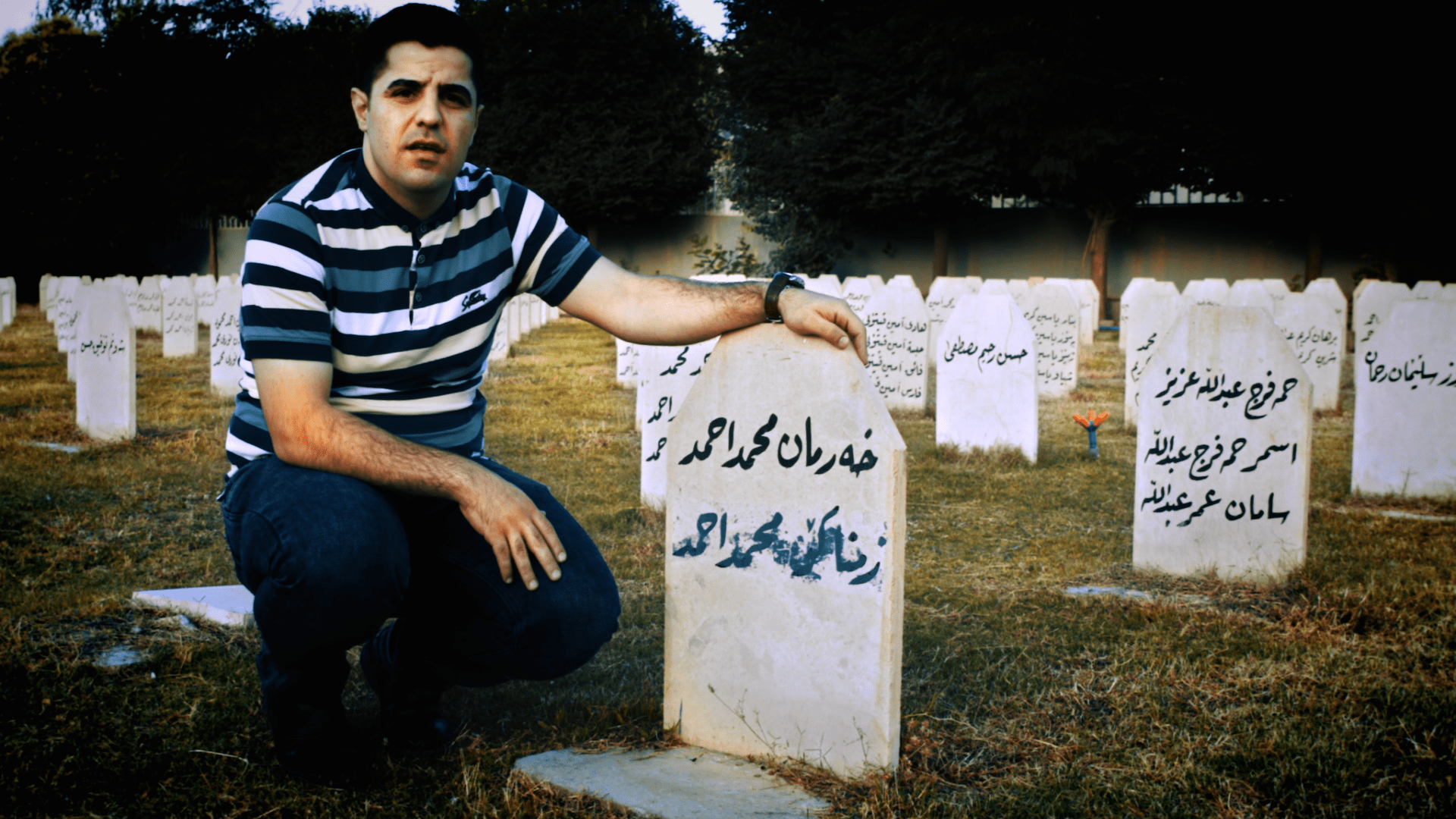

Zimnako Mohammed posed for a photograph in front of his own gravestone in one of Halabja’s many cemeteries for people killed during the Iraqi poison gas attack in the spring of 1988.

‘It’s a very strange feeling to have your name on a headstone before you’ve died,’ he says. ‘But this shows the scale of Halabja’s tragedy.’

Some 5,000 people perished and up to 10,000 were injured in the attack on March 16. Zimnako, then a three month old baby, was believed to have died along with his entire family. He was one of 100 babies from the town who were registered as lost, and he was the first to return home searching for his family.

It’s a very strange feeling to have your name on a headstone before you’ve died

Despite the mass graves in the town, Halabjan families who lost children during the attack have never given up hope that they could still be alive. Zimnako’s homecoming – and those of a handful of other missing children – has convinced them that their relatives could have survived.

When he returned at last from Iran to Halabja 21 years later in October 2009, Zimnako was reunited with his mother, Fatima Hamasalih Mahmoud, and found out what had happened to the rest of his family as well as the people of Halabja.

WARNING: THIS FILM CONTAINS GRAPHIC CONTENT VIEWERS MAY FIND UPSETTING. Kurdish townspeople who lost close relatives in the Iraqi army’s vicious chemical gas attack on the city of Halabja recall the horrors they endured. About 5,000 people died and more than 7,000 were injured within hours.

When Iraqi planes bombed Halabja with chemicals, Zimnako’s family sheltered in what they thought was the safest place in the house, the basement.

After the sound of bombing stopped, they ran into the street intending to leave Halabja. But his parents panicked when they thought they saw a chemical shell exploding nearby.

His father, Mohammed Mama Ahmed Kulkni, led them back into the house and went upstairs to the roof, believing they had more chance of surviving in the open air than in an enclosed underground basement.

Zimnako’s father believed his family had more chance of surviving the chemicals in the open air than in an enclosed underground basement

Zimnako’s father was followed by his son, Sartip, who collapsed screaming for help because chemicals were burning his skin. His mother, Fatima, who was holding baby Zimnako in her arms, put him down on the ground while she fetched a wet cloth. She wiped Sartip’s face three or four times but then lost consciousness.

Sartip died shortly afterwards, as did his father, his sister Kharman, and three other brothers, Ghazi, Ako and Sarko.

Mahmoud, a survivor of the chemical bombardment of Halabja, describes how more than 140 people died in his cellar. He remembers stepping on the body of his wife as he escaped into the street outside his house. His daughter survived but suffered a psychotic breakdown.

After collapsing at her home in Halabja, Iraq, Fatima awoke from a coma to find herself in a hospital in Kermanshah in Iran near the border. She had no idea how she had got there nor the fate of her family. When the Iranian Red Crescent Society distributed clothes in the hospital to Halabja gas victims, she took garments for all her children as she believed they were still alive but scattered in different refugee camps.

Baby Zimnako had also been taken to Iran for medical help, apparently by Iranian soldiers, and driven by ambulance to a kindergarten in Mashhad close to Iran’s Afghan border. He was given into the care of Kubra Hamidpour, an Iranian widow who worked there looking after children whose fathers had been killed in the Iran-Iraq War. She took Zimnako home and brought him up as her own son.

Meanwhile, after Saddam’s defeat in Kuwait by Coalition forces in 1991 the inhabitants of Halabja slowly returned home to experience almost unimaginable scenes of horror. They found the decomposed remains of hundreds of relatives in the cellars where they had sought refuge from the chemical gas clouds three years earlier.

In one basement alone, a survivor discovered 122 bodies – 86 of them relatives. In another, as many as 200 corpses were discovered. The bodies of the dead were taken to the Martyrs’ Cemetery in Halabja, where they were interred in a bomb crater.

Grief gripped all the returnees. “When I returned home,” said one survivor. “I found all my relatives had died. I was so upset I didn’t now what to do. I went crazy looking at the walls of my home and remembering the happy times we’d spent together.”

Halabja survivors return home from Iran in 1991, three years after the Iraqi army attacked their city with chemical weapons. Searching for the remains of their close relatives, who are all presumed dead, they find up to 500 bodies in a single location before burning and burying their remains.

Zimnako’s mother never concealed the fact that he was adopted and from Halabja. He grew to love her as if she was his real mother.

‘She was the only person I had in my life,’ says Zimnako. So when Kubra was killed in a traffic accident 16 years later, he was immensely upset. His two adoptive brothers were married before their mother’s death and moved away from the family home, so Zimnako was left to cope on his own as a teenager.

‘It was the hardest time of my life,’ he says. ‘I kept on asking myself, “Why should I lose two families – one in Halabja and one in Iran? What sin have I committed?”

‘I had nothing left to live for. I was about 16 when I lost her and I really needed someone to help me in my life. All of this led me to conclude that my existence was pointless.

I kept on asking myself, “Why should I lose two families – one in Halabja and one in Iran? What sin have I committed?”

‘I came back to the house and everything reminded me of her. But then I thought, “I have to be brave enough to continue. I have no other choice. This is my life and I have to accept it and go on.”’

But living in Iran as an Iraqi national brought its own particular problems. He was not permitted to go to university and finding proper employment was difficult. Even playing football for the local team seemed impossible. ‘I wanted to play in a cup tournament with my friends, but because I wasn’t Iranian I wasn’t allowed,’ says Zimnako.

He survived by working illegally in a teahouse whilst approaching numerous governmental organisations in Iran for help.

He pleaded with the Iranian authorities but their response was always negative. ‘I was living with my friends, we grew up together, I spoke like them, the only language I knew was Persian – but when it came to getting my ID papers, I was different.’

‘I always told them, “You took me from Halabja, so you must do something about me.” But they said, “No, we cannot make a special case just for you.”’

I told the Iranian authorities, “You took me from Halabja, you must help me find my real family.” But they would always say, “We cannot make special cases”

Zimnako contacted UN agencies and foreign embassies but his efforts proved fruitless. His luck changed, however, when he approached the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) through an intermediary in Tehran.

He met with Chnaar Saad Abdullah, the KRG Minister for Martyrs and Anfal, who was on an official visit to Iran. She told him that about 60 Halabja families had lost their children during the 1988 chemical attack.

‘At that moment, hope entered my heart that I could find my real family,’ says Zimnako.

His search, helped by the KRG, finally took him to Halabja in August 2009. Blood samples were taken and DNA tests carried out in Jordan.

ZIMNAKO MOHAMMED survived the Iraqi army’s chemical gas attack on Halabja as a three-month-old baby. He was taken to Iran, apparently by Iranian soldiers, where he was adopted and treated with kindness. After 21 years away, he returned home to Halabja in the hope that DNA tests would reveal the identity of his biological mother.

As Zimnako waited for the results, he began to face up to the possibility that, like many others in Halabja, all his close relatives might be dead.

However five families claimed him as their own, all convinced he was their missing boy. ‘I became a son for each of these families,’ he says.

In October, all the families assembled at the Halabja Monument to hear the results. As they were announced, Zimnako thought lovingly of his Iranian adoptive mother who promised him she would only surrender him to his real family. ‘I felt her soul was with me at that moment. I looked at her picture on my phone and I cried.’

As I waited for DNA results that might reveal my biological family, I felt the soul of my adoptive Iranian mother was with me

When Fatima Hamasalih Mahmoud was named as his mother, Zimnako felt he had been granted a new life.

‘My real mother had lost everyone but now I had returned to her. She was happy and I was happy but I was also thinking of the other families and their losses.’ Before embracing her, he kissed them all and said, ‘Do not worry. I am still yours.’

‘It was a very difficult moment for them,’ says Zimnako. ‘This is the tragedy of Kurdistan. There was some happiness at last for my family but the consequences of the chemical bombardment of Halabja will last forever.’

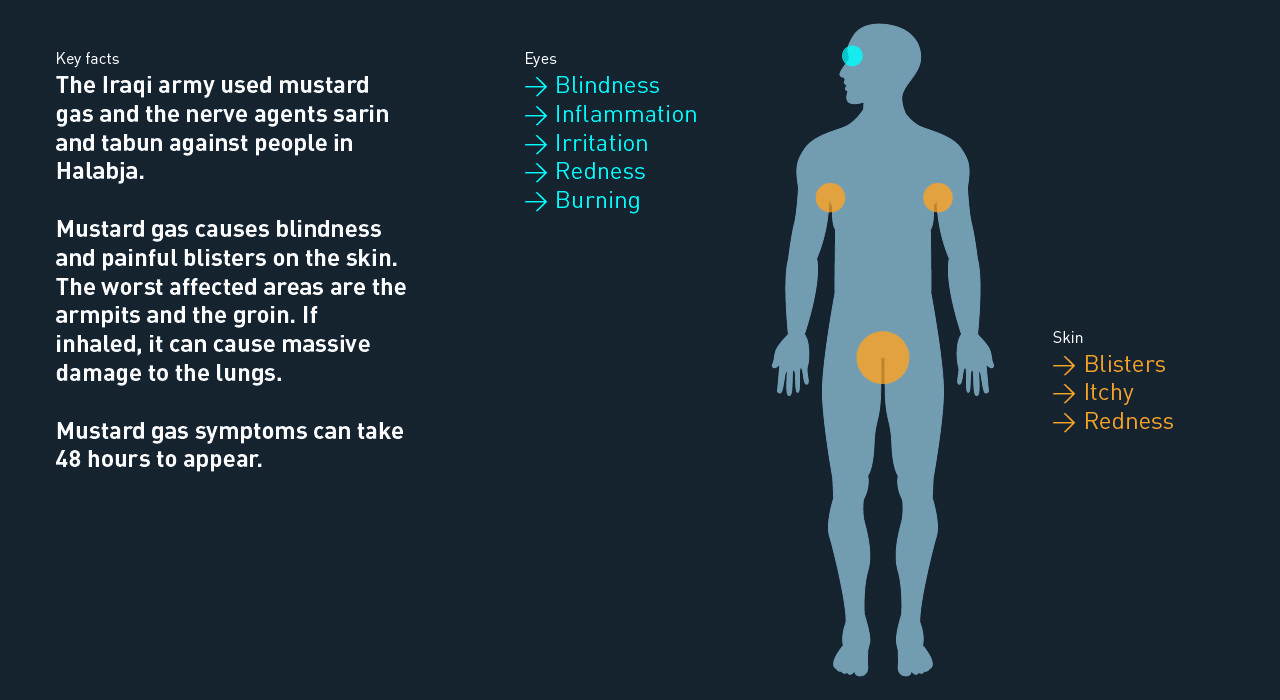

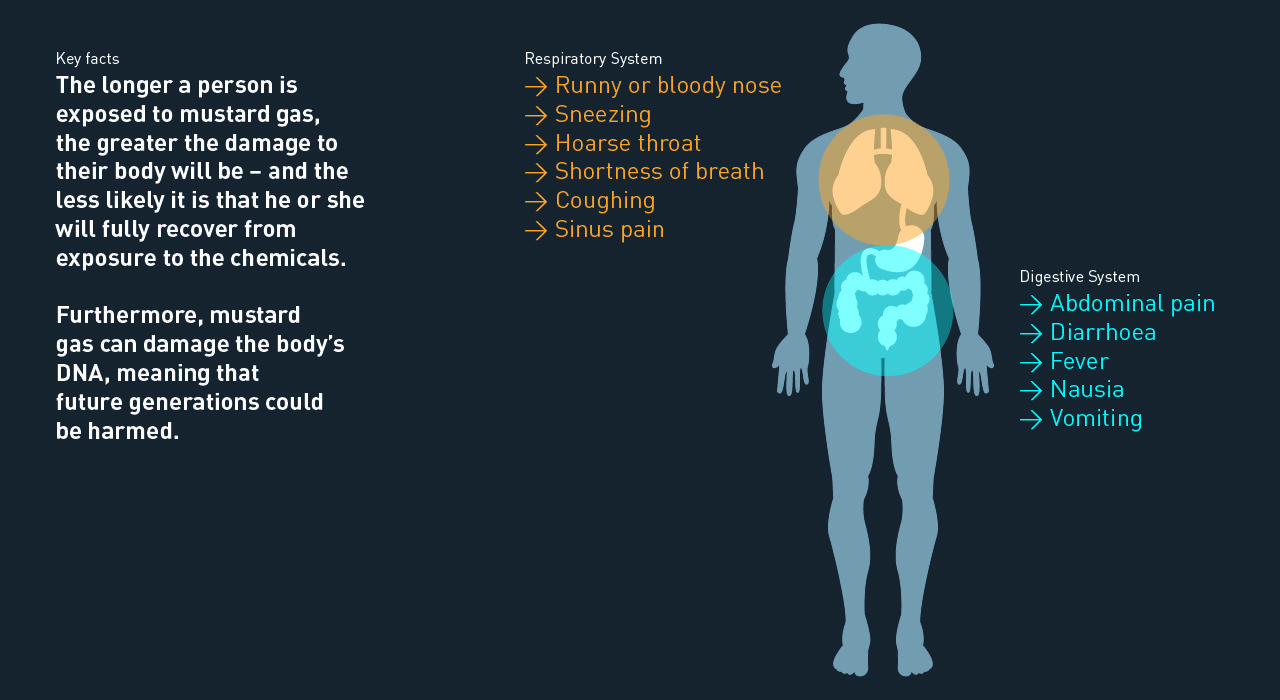

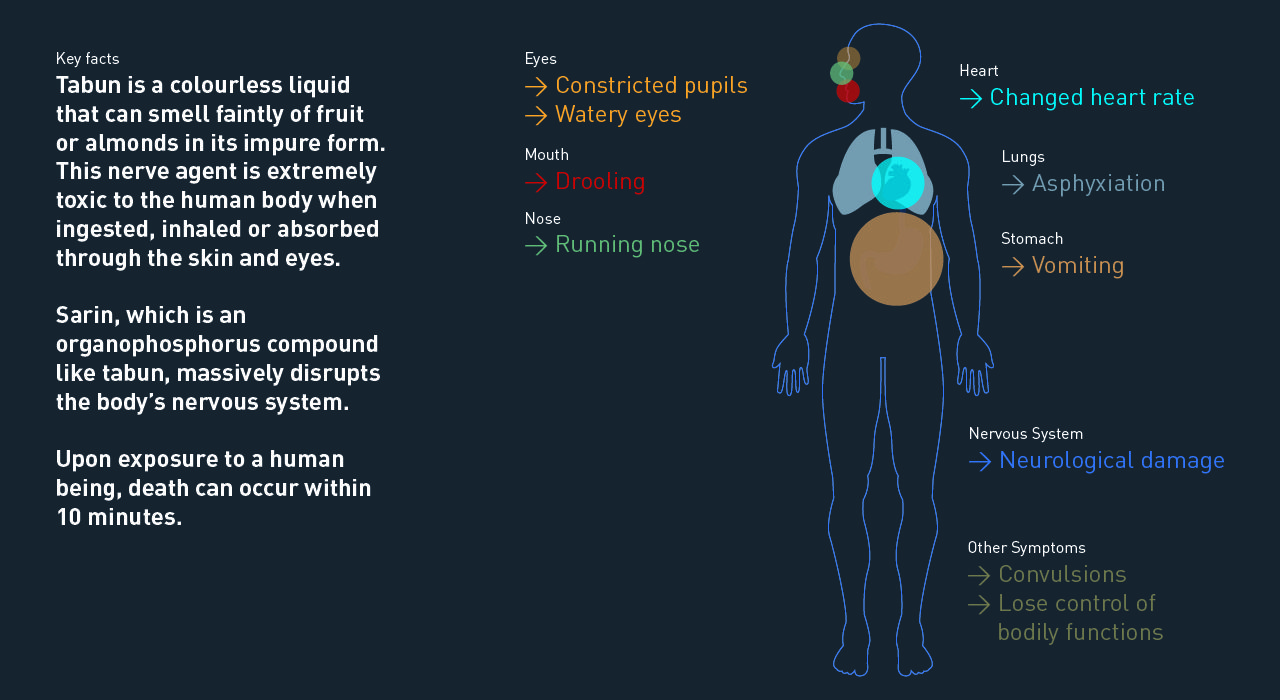

Halabja still counts the human and environmental cost of the Iraqi army’s chemical gas attack to this day. When a British documentary team visits the city with a medical specialist 10 years afterwards, they find unusually high rates of respiratory complaints and cancers amongst children, not to mention high levels of mental trauma amongst survivors.

Halabja has indeed been left with a terrible legacy. Decades after the attack people from the city still suffer from the effects of poison gas – through psychological or physical damage – and there is a chance that future generations could suffer genetic changes as well.

Already there is a high incidence of cancers with people from Halabja three or four times more likely to get some form of the disease than elsewhere. Half of Halabja’s affected population have respiratory complaints and many women who conceived children before 1988 were unable to have children after the Iraqi attack. However, babies in Halabja born since the attack often suffer from severe abnormalities consistent with genetic damage.

I accept what happened to me as a baby in Halabja but I pray my children never have to go through what I suffered

However, Zimnako displays an enormous determination to overcome his difficult past.

‘I found my real family,’ he says. ‘I have rebuilt my life, I have a degree, a good job and have got married.’

‘I accept what happened to me but I pray my children never have to go through what I suffered.’

Hundreds of those who escaped the Iraqi army’s chemical attack on Halabja were lost to their families afterwards. BARZAN MOHAMMED BAQIR and AZAM MOSYA RAHIM were two such children and grew up in Iran. Now fully grown, they return to Halabja in March 2016 in the hope that DNA tests might help reunite them with extended family who survived the apocalyptic attack.