When poison gas bombs struck Sheikh Wasan on 16 April 1987, villagers ran towards the sound of the explosions to investigate what damage had been caused, unaware of the dangers they faced.

Salam Hussein Aziz from Balisan village was alone in his house during the attack. His wife was visiting relatives in Erbil and he was about to make dinner when he heard planes overhead. Salam took cover in a nearby cave along with many other families.

The bombs exploded on impact but this time they were not as loud on impact as in previous raids. Afterwards everyone emerged from their shelter eager to find out what had happened.

It was very a tragic scene. Entire houses had been razed and burnt

A strange smell hung in the air as cooking odours mingled with the tang of chemicals.

‘I thought it might be the smell of the food because people were cooking and left their food on the fire,’ says Salam Hussein Aziz. ‘People went right up to the explosion sites as they did not know about chemical weapons.’

They tried to dispel the fumes by lighting fires. ‘It was 9.30 pm and very dark, and we gathered around the flames. Some of us could no longer stand on our feet, some were vomiting and some screaming in pain, their skin burnt and their eyes watering,’ says Salam.

He and another neighbour moved families up the mountains then returned to look for stragglers who were too weak to leave with the others. He brought a doctor to help treat those who were comatose but everyone fled when the army began its ground offensive.

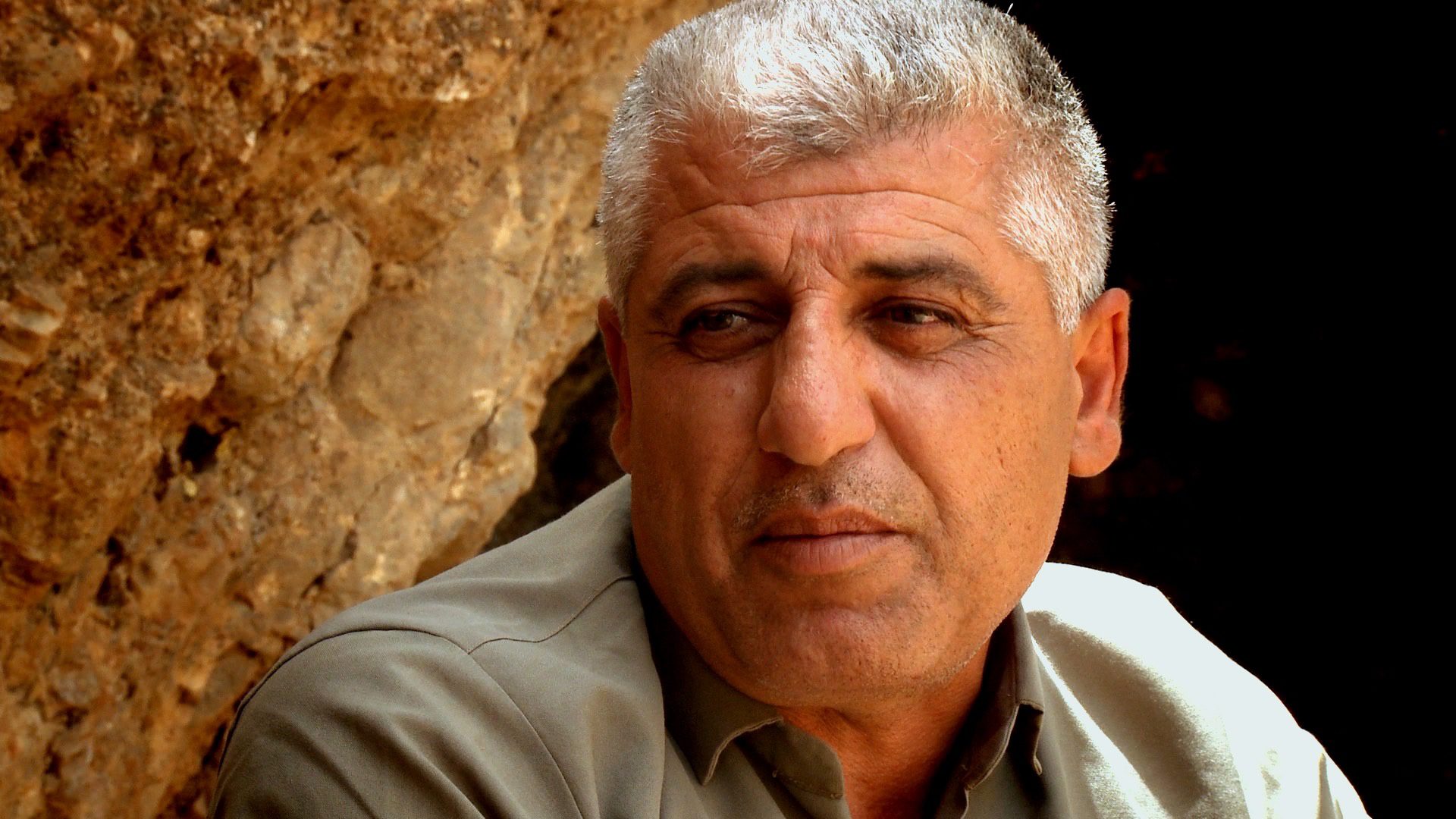

In April 1987, SALAM HUSSEIN AZIZ witnessed Iraqi planes bombing Sheikh Wasan village. He saw how villagers, unaware of what poison gas was, went close to the bombs and were immediately affected by the toxic fumes. He helped survivors move away from the scene of the attack.

Salam headed to Hawiri mountain with a peshmerga fighter and from there watched the Iraqi army entering the village. After the troops left, they returned and saw how their homes had been levelled. ‘It was very a tragic scene. Entire houses had been razed and burnt, and they’d used bulldozers and TNT,’ says Salam.

He stayed on in Balisan with eight peshmerga. Eventually his family returned with a few others. They survived amidst the ruins of their village but the following July 1988 the planes returned to launch another poison gas attack.

Salam donned a gas mask and wrapped his children’s faces in wet cloth as the gas cloud moved towards them. He ran towards a peshmerga base with his children in his arms but as he ran he dislodged the scarf from his son’s face. The boy died.

Thanks to his gas mask Salam survived, but he was so weak that he had to ride back to the peshmerga base on horseback

In shock, Salam left his son’s body at the base and ran back to the village calling the names of his family as he approached his house. He reached home and found the bodies of his wife and friends. Another woman lay motionless on the ground holding her dead child close to her chest.

Thanks to his gas mask, Salam survived but he was so weak that he had to ride back to the base on horseback. There he was given an antidote injection and transferred to a peshmerga clinic. He was hidden by relatives in Saruchawa village near Balisan until the Iraqi regime issued a general amnesty in late 1988. Ever since, he has suffered chest pains and severe emotional and psychological damage.

Salam remarried and in 1991 joined the Peshmerga uprising.

SALAM HUSSEIN AZIZ’s baby son died in his arms after a chemical attack on the Balisan valley in 1988. He found the bodies of his wife and other children in a shelter close to Sheikh Wasan village.